The Great Man --- Part Two

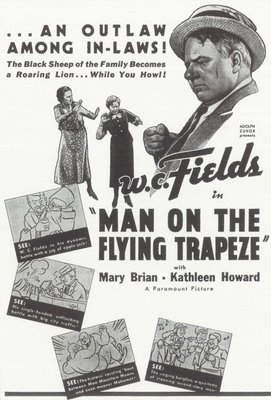

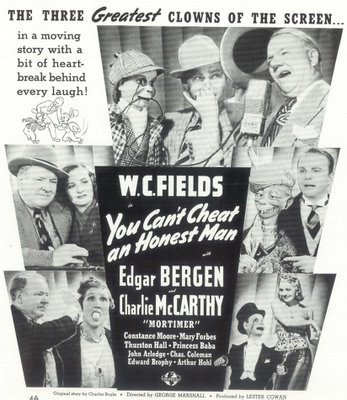

Sixties Fields cultists preferred the charlatan. Domestic purgatory was a less inviting prospect for college audiences who were themselves on the cusp of lifetime commitment and adult responsibilities. Might we end up like Bill, with a hectoring shrew of a wife and rotten kids leaving roller skates in our path? It’s A Gift was a disturbing forecast of the darker possibilities of life after school. Better to enjoy Larson E. Whipsnade lording it over suckers and outwitting the sheriff. Fields was dominant in those situations. That’s still how we remember him best. Family Man Fields was submissive --- Carnival Fields prevailed. My own early exposure tended to favor Poppy, You Can’t Cheat An Honest Man, Mississippi --- anything with the promise of carefree maturity where chumps finished last and all your opponents came away with empty pockets. The flip side was more disturbing because this was where Fields sought to impart some truth about our futures, and You’re Telling Me, The Man On The Flying Trapeze, and especially It’s A Gift (great comedies all) reveal that life, particularly family life, isn’t pretty. He actually preferred making these. They allowed him to record incidents as he recalled them, people as he understood them. You just assume that everything happening to Bill in these features had naturally occurred in his real life. It was too honest and accurate to have been made up. There were writers, but everything in the end was his. Paramount had no choice but to let Fields run the show. No one else shared his demons, certainly no one could loose them in such a way as to produce the laughter he did.

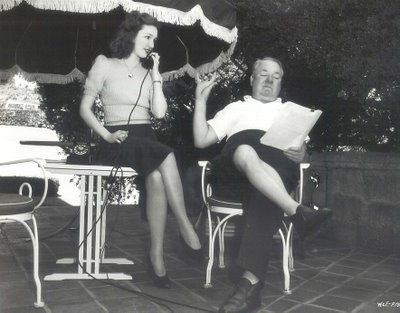

Fields needed directors who knew comedy, preferably men who’d been on the road in stock and vaudeville as he had. Youthful talent like Leo McCarey (Six Of A Kind) was at first regarded with suspicion, and those who’d come from differing backgrounds, such as trained in art direction Mitchell Leisen, became sworn enemies. On The Big Broadcast Of 1938, Leisen’s antagonism was such that he simply turned over to Fields the management of his own comic highlights, the happy result being, among other things, the gas station and golf game sequences that open the film. As long as his comedies were made for a price (preferably a low one), Fields enjoyed a remarkable degree of creative freedom. I think another secret of his on-set control may have been an apparent willingness to just walk away. He’d avoided much of the personal overhead that otherwise chained contract talent to studios. Fields liked to plead poverty (according to him, nobody laughs at a rich man), but was always comfortable enough to give the bird to overbearing employers. Stills of Fields at home (seen in Part One) reflect contentment with a good life that included cooking staff (receiving menu instructions from him here) and private tennis courts (Fields was quite an athlete in his prime). Health problems were the real downfall, exacerbated by alcohol. It seemed as though each new Fields picture would be his last, and there were lengthy periods of absence from the screen. Radio was a happy solution at first, but the pressure of coming up with funny material on a weekly basis created stress beyond anything he’d experienced at Paramount, and broadcasting became almost as sporadic as his movie appearances.

Fields was long since estranged from wife and child, but they would resurface from time to time throughout his life, and in fact, he did have a reapproachment with son Claude toward the end. Otherwise, there was a series of mistresses in and out of Field’s life, most notable of these being the strikingly beautiful Carlotta Monti, who lived long enough to profit from the latter day revival with a memoir about their years together. She's (above) playing Field’s secretary, a real life role as well, in The Man On The Flying Trapeze (1935). I’d heard for years how Fields wrote stories on backs of envelopes and bamboozled fortunes out of Universal for their screen adaptation. Alas, that appears to be yet more studio banana oil Don Lockwood talked about, for in fact, Fields poured tremendous effort into preparation of four comedies he did for Universal. These would become the comedian's primary legacy thanks to successful theatrical re-issues mounted during the late sixties and seventies. Fields was fairly trapped by the flamboyant image he and press agents fostered over the years, so he was less a human being than some Dickens character brought to life (as most convincingly, in David Copperfield). That attempt to cast him as The Wizard Of Oz came very close to reality, but delays and prior commitment to do You Can’t Cheat An Honest Man put paid to that tantalizing possibility. Would his presence in Oz have been too overpowering? He’d surely have embellished the role, and we’d naturally want more of him. Fields might well have played off other characters more effectively than Frank Morgan --- but would The Wizard Of Oz have suffered for all of us just waiting for our man to show up?

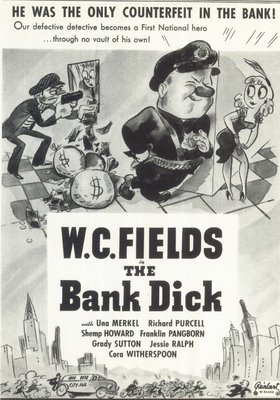

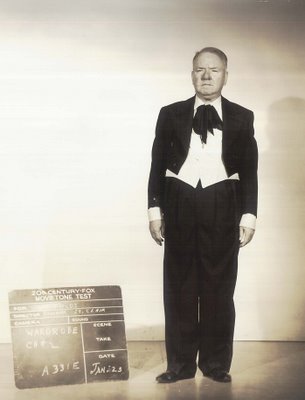

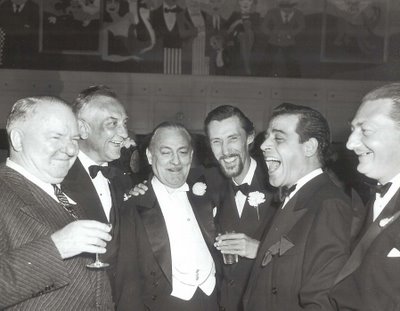

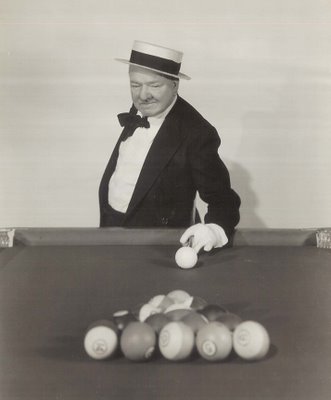

This merry group you see with Bill includes a well-lubricated John Barrymore, John Carradine, and John Decker, among others. It was this sort of company that laid Fields low during final years when he couldn’t get insured to do another feature. Audience apathy was another factor. James Curtis writes that The Bank Dick and Never Give A Sucker An Even Break were both D.O.A. at the B.O., so Universal wanted no further part of him. From here on in, screen work would be limited to specialty appearances and "guest" cameos (here playing pool in one of them, Follow The Boys). The costume test is from Tales Of Manhattan, but Field's contribution to that omnibus feature was cut prior to release, despite preview audiences who said it was the best thing about an otherwise unremarkable show. Now it’s back at last, in a DVD compilation of Fox outtakes, and Field’s footage is alone worth the price. One of his secretaries from those idle years (could it be the one seated outdoors with him here?) recalled Bill only once using his stage voice, and that when they encountered some fans while out on a drive. I wonder what W.C. Fields did sound like when he wasn’t being W.C. Fields… Anyway, toward the end he speculated as to how things might have turned out had he left the whisky alone. A longer life perhaps, but he surely wouldn’t have been the Fields we know and revere.