The Great Man --- Part One

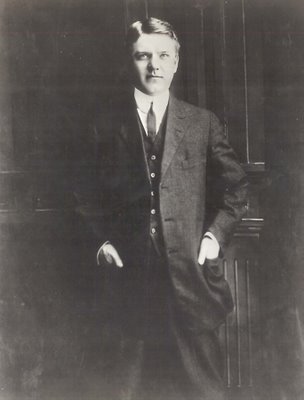

The Great Man --- Part OneThere was a time when W.C. Fields seemed eternal. His persona, his philosophy, seemed to embrace succeeding generations long after he’d left the stage in 1946. A fan following as yet unborn would replace the audience that filed out when he died. Field’s image was a pliable thing that somehow renewed itself and spoke to the children, and grandchildren, of those who saw him first. I grew up thinking he’d always be around, but by the present look of things, it would seem we’ve lost Uncle Bill. Universal’s DVD set of two or three years ago was seemingly their final word on the subject. You’d like to think they’d release the rest of them, but where are those teen-agers and college students of yore that lined up at revival theatres and University campuses to see him? Their numbers have not been replenished --- how can they when the films are long since out of general circulation? My generation had comparatively easy access to him. Kids today haven’t seen Fields on TV since TCM ran off a package at least five (?) years ago. Universal should have nourished this franchise better. Harold Lloyd was late coming back (maybe too late) and Laurel and Hardy remain lost in the wilderness (at least insofar as their best films are concerned), while Chaplin, Keaton, and The Marx Brothers have flourished. Is it still possible for W.C. Fields to (re)claim his rightful place on the comedy pantheon?

I recently listened to a radio program from February 28, 1956 entitled Biography In Sound (you can hear it too, and for free, right HERE). This episode was called Magnificent Rogue --- Adventures Of W.C. Fields, and Fred Allen was the host (Allen died within weeks of the broadcast). This being fifty years ago, there are some pretty incredible interviews spread over the hour-long program --- Leo McCarey, Mack Sennett, Errol Flynn, Baby LeRoy --- what a line-up. Coming within a decade of Field’s passing, this is very much a collection of show-biz anecdotes recalled while reasonably fresh on the minds of their tellers, and you really get a sense of Fields as the outrageous non-conformist they all wish they could have been. I gathered it was easier for these veterans to applaud Bill from the comfortable distance a decade had given them, for his actual life had been anything but cakes and ale.

The biography of Fields was written by James Curtis and published in 2003. It’s the best book on the man I’ve ever read. If you have any interest in W.C. Fields, you will do yourself a service ordering it HERE. Curtis really puts a human face on what had to be a difficult subject. I’ve always liked Field’s comedy, but everything I’d read led me believe he was little more than an unapproachable variation of the most anti-social aspects of his screen character, a person I would have actually been afraid to meet. It was the same way with Groucho Marx --- you just knew these guys would likely tell you to go to hell and leave them alone, whereas someone like Stan Laurel might invite one to sit down and visit a while. Those sorts of imaginings tend to color my perception of all these comedians --- yes, it does matter what kind of people they were off-screen. I’m now reconciled with W.C. Fields, thanks to Curtis --- at least I understand him better, although any real identification would require first-hand experience with childhood traumas and youthful influences I’d not likely have survived. Hardship Fields overcame shocks the conscience and makes you realize just how pampered most of us are in a computerized world of plenty. I’d not appreciated what a violent world he lived in. There were beatings from his father, street crimes in which he might be a victim one day, assailant the next. Fields routinely resorted to near-deadly force in settling arguments, and this didn’t necessarily end when he stepped before footlights. The Follies legend of how he broke a pool cue over Ed Wynn’s head during a routine was likely true. Fields didn’t like his rival’s on-stage intrusion and retaliated in accordance with his background and experience. He was a dangerous man to trifle with.

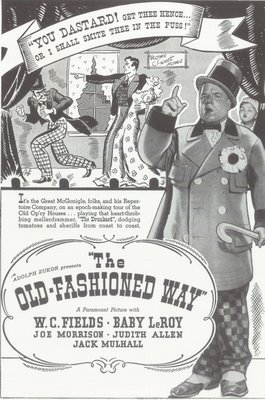

Vaudeville and variety must have been drudgery. Juggling was the start, but later the routines required custom props transported from town to town, and they didn’t fit in overhead compartments. The precision required precluded alcohol use, but when dialogue and verbal humor gained precedence, Fields took to the bottle with a vengeance, and movies allowed for an even more sedentary lifestyle. The silent Fields is largely unknown to us --- those ones that aren’t lost are seldom shown. He wore a grubby little clip-on mustache in all of them, just the thing to remove even the remotest possibility of audience sympathy for him. Ill-judged pairings with grotesque comics of a Chester Conklin sort emphasized retro aspect of these vehicles --- they even remade Tillie’s Punctured Romance in the late twenties (now lost). Many of the routines he’d immortalize in talkies were introduced here, but played silent, they were deadly, and real stardom wouldn’t be achieved until he could step in front of a microphone. Even then, it was slow getting to the top. Paramount used him in all-star concoctions --- this is the beginning of the Fields we know. Watching International House amounts to fairly equal doses of ambrosia and castor oil. When Bill’s on (especially in a parlay with Bela Lugosi), there’s no better comedy to be had, but when it’s Stuart Erwin and Peggy Hopkins Joyce bickering on a mock-up desert soundstage --- lights out. The best Fields work prior to 1934 may well be the four Mack Sennett shorts, which were actually the first exposure a lot of us had to Fields. They were available in 8 and 16mm during the sixties and seventies from Blackhawk Films (one of them, The Barber Shop, is shown here) and it’s no telling how many runs these things had in schools, libraries, YMCA’s, birthday parties, you name it. I remember playing The Dentist once in a gymnasium filled with college students for what we advertised as a BYOB show (that’s Bring Your Own Bottle for the uninitiated). There was something distinctly Fieldsian about that combination of his voice reverberating off cinderblock walls and drunken hoots and catcalls that accompanied the screening. Maybe this is just the sort of exposure his films could use today.