Beginning Of The End For John Gilbert

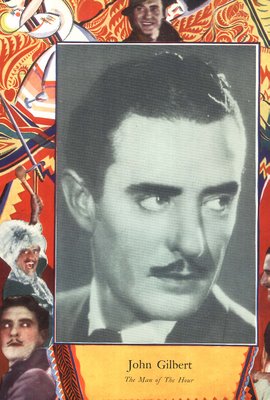

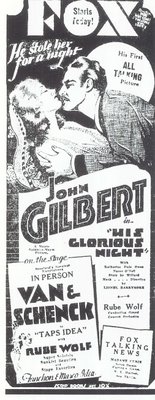

I have never understood the collapse of John Gilbert’s stardom that followed the coming of sound. He’d been the screen’s "Man Of The Hour" (as witness this trade ad) and had appeared in an unbroken string of profit pictures, some of these among the biggest hits of the silent era --- The Merry Widow, The Big Parade, Flesh and The Devil. Even the least of his formula vehicles consistently went in the black --- The Show, Four Walls, Masks Of The Devil. The myth of a "white voice" was disposed of years ago, but it died hard, and carried a lot of persuasive force for many decades after Gilbert’s career had been smashed by its cruel implications. How could a man at the very summit of popularity find himself so completely discredited within less than a year, abandoned by the public, his pictures losing money one after another? It all happened between October of 1929 and the autumn of the following year, when The New York Times would refer to Gilbert’s following in the past tense. Contrary to legend, it was not an "overnight" plummet brought on by His Glorious Night. Indeed, that one was a financial success, and it wasn’t Gilbert’s talking debut in any case.

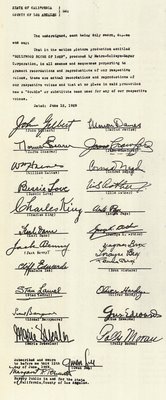

He’d started 1929 with another hit, albeit silent (featuring synchronized music and effects). That was Desert Nights, which opened in March. Gilbert’s voice had actually been heard from the screen prior to this, in a special short (Voices Across The Sea) commemorating the opening of the new Empire Theatre in London. He was shown exiting the lobby with Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, and Marion Davies, joining in their chorus of praise for the lavishly appointed showplace. This subject would have seen little play in the U.S., but it was John Gilbert’s debut in sound. Most of MGM’s other artists made talking bows in The Hollywood Revue Of 1929, which had its opening in June of that year, and ran through remaining months to enormous crowds ($1.1 million profit). Concern over voice authenticity resulted in an affidavit (shown here) in which all the stars "certify" they’ve not been doubled for purposes of recording. Gilbert and Norma Shearer contributed a rendition of the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, first played straight, then spoofed up with twenties slanguage. Two-color technicolor augmented what surely was considered the highlight of this show and the stars even let their hair down for a comic exchange with director Lionel Barrymore. Gilbert plays the Shakespeare in earnest fashion, acquits himself well during the lampoon portion, then relaxes and appears to ad-lib in his concluding exchange with Shearer and Barrymore. This could not have been considered anything but an auspicious talking showcase for the actor, and audiences responded accordingly. No published review I’ve seen had anything other than praise for Gilbert in The Hollywood Revue Of 1929.

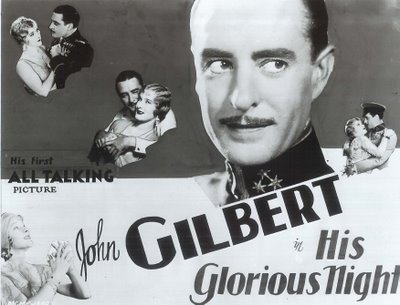

Was Louis Mayer out to get him? There was another of those real-life Hollywood dramas in which Gilbert was supposed to have punched the studio executive's face when Mayer made an indelicate remark about Greta Garbo, long recognized as The Great Love of Gilbert’s Life (here during a brief shack-up period they’d recently enjoyed). Greta had allegedly stood up Jack at the altar that very day, and tempers were running high, so much so that a bloodied Mayer swore he’d finish John Gilbert if it’s the last thing I do (or words to that effect). Later research suggests that Garbo was at work that day and never intended to marry Jack or anyone else. I suspect this is one of those stories too good to debunk, and since it had its origins with long-retired silent star eyewitnesses (Eleanor Boardman chief among them), how can anyone say with certainty that it didn’t happen? There was hostility toward Gilbert within Mayer’s camp, but this was owing to the fact that Loew’s head Nicholas Schenck had quietly pledged Gilbert to a renewal of his contract at fantastically generous terms (and without consulting Mayer) in December of 1928. This New York office chicanery tended to undermine the authority of the studio bosses where talent was concerned, but what could they do? --- Loew’s owned MGM, and Schenck required neither their permission nor approval. This was probably where John Gilbert really lost his moorings, and one couldn’t help but smell a rat by the time His Glorious Night showed up in October 1929.

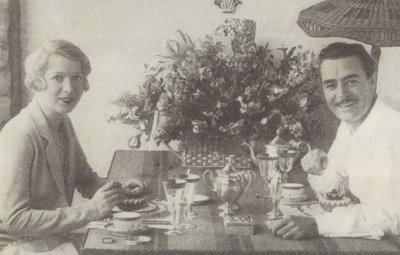

The biggest stink bomb chucked in Gilbert’s direction came from Variety. None of the other reviews approached this one for sheer vitriol. I’m convinced it was a ringer, planted there to start him down the skids. A few more talker productions like this and John Gilbert will be able to change places with Harry Langdon. His prowess at love-making, which has held the stenos breathless, takes on a comedy aspect in "His Glorious Night" that gets the gum chewers tittering at first and then laughing outright at the very false ring of the couple of dozen "I love you" phrases designed to climax, ante and post, the thrill in the Gilbert lines. Variety’s snide review went way beyond other critical reactions to the film. Both Mr.Gilbert and Catherine Dale Owen contribute competent performances, said The New York Times, and exhibitor reaction, which could be tactless and brutal in the best of times, reserved their brickbats for the film itself and specifically Metro’s sound recording, while others praised His Glorious Night and limited complaints to what they considered unreasonable rental terms ($85.00 in one situation). John Gilbert returned from his European honeymoon with Broadway actress Ina Claire just after the picture opened (here they are at afternoon tea), and according to a later interview, found Metro publicists waiting at the dock in gleeful anticipation, scathing reviews clutched in their hands. Maybe Gilbert’s memory was colored by the truly awful developments he’d witness over coming months, because at this point, the only scathing notice was Variety's --- The love lines, about pulsating blood, hearts, and dandelions, read far better than they sound from under the dainty Gilbertian mustache --- another vicious quote from that very suspect review. General press coverage would eventually follow suit --- bad Gilbert pictures wouldn’t help. Redemption was actually shot before His Glorious Night, but adjudged so lousy as to be shelved for nearly a year. 1930 would see the release of that and creeping doubt as to John Gilbert’s boxoffice future. Mind you, Redemption was the first of his MGM output to lose money (His Glorious Night had returned $202,000 in profits). The power of suggestion (but whose?) had finally extended to The New York Times by September of that year --- John Gilbert, who was once the great lover of the silent screen, cannot be said to have maintained his lofty position since dialogue was coupled with films. He has only appeared in two films, which have not increased his popularity. He has recently finished work in another audible film called "Way For A Sailor", which so far has not been presented, and on which his future screen success depends largely. Well, in such circumstance as this, how could Way For A Sailor be anything other than a failure? Indeed, it would tank ($606,000 lost) as would every single Gilbert vehicle to come (excepting Queen Christina, but that was Garbo’s show, and Gilbert’s was charity casting). Chaplin tried to throw him a lifeline by announcing a forthcoming slate of silent dramas to star Gilbert --- in March 1930 --- but this was likely more of CC’s posturing against the encroachment of sound and not to be taken seriously.

I finally realized a near-lifelong dream of seeing His Glorious Night at the 1997 Cinecon. It was a movie I’d read about since Arthur Mayer and Richard Griffith’s The Movies book back in sixth grade, and Gilbert’s voice, though nowise approaching a Ronald Colman or William Powell, was still more than adequate, even if it’s not what we’d expect of the silent Gilbert. It seems to me the man was wiped out less by the failure of his performance and popularity than by the perception of failure, fed by a press and public easily influenced by rumor and suggestion. It happened to Burt Reynolds in the eighties, and we still see parallels today. The recent course of Tom Cruise’s career comes to mind, and there are others. Stardom was seldom so fleeting a thing as John Gilbert experienced it, but no actor, today or the day after tomorrow, should ever imagine that this couldn’t happen to him.