Welcome To the Inner Sanctum

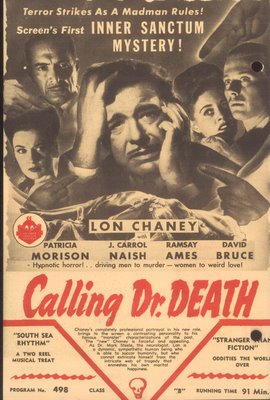

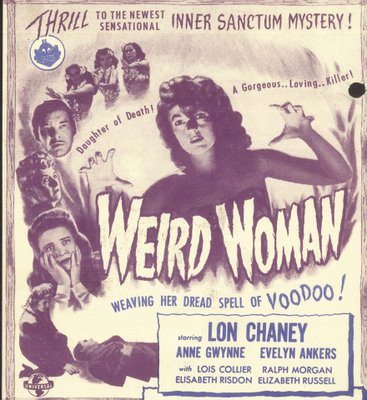

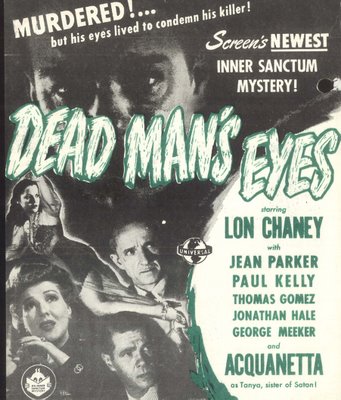

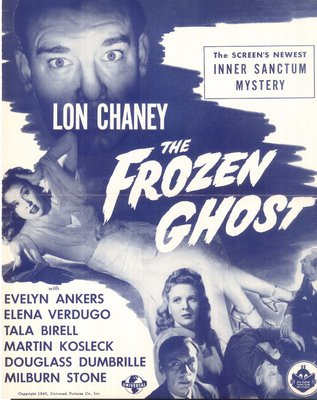

Inner Sanctums are neither fish, fowl, nor mammal. They aren’t horror movies, even if their presence on the old Shock Theatre implied they were. They’re not film noir --- we’d be stretching that term beyond its already fragile limits to include them. To a degree, you could call them mysteries, but we think of those in terms of a series format with charismatic continuing characters, like Charlie Chan or Sherlock Holmes. A single common thread weaves through all six Inner Sanctums, that being Lon Chaney (Jr.). You’d have thought Universal would cast Chaney as the police investigator or private eye that breaks the case and unmasks the killer(s), but detection is only incidental to these pictures. Chaney’s usually the object of suspicion --- brooding, tormented, and often as not, sharing his misery with the audience by way of voiceover monologues labeled Place Exposition Here. Lon’s got to be the most sedentary mystery series lead I’ve come across --- an obtuse, long-suffering punching bag for all variety of machination practiced upon him by revolving casts in support. Evelyn Ankers very nearly frames him for murder in Weird Woman, J.Carroll Naish ruthlessly exploits him in Strange Confession, Patricia Morrison has him bound for the hot seat in Calling Dr. Death. Introduce a best friend or sweetheart for Chaney in the first reel of a Sanctum, and they’ll almost certainly be revealed as the killer in the last. Nobody in movies was played for such a sap as Lon in a Sanctum. Watch all six end to end and you realize Universal pretty much sized him up for one offscreen as well. The Sanctums may have seemed like a welcome change of pace for an actor determined to break the cycle of low-budget horror films, but by the time this series played out, Chaney was wrung dry, all his limitations having been cruelly laid bare…

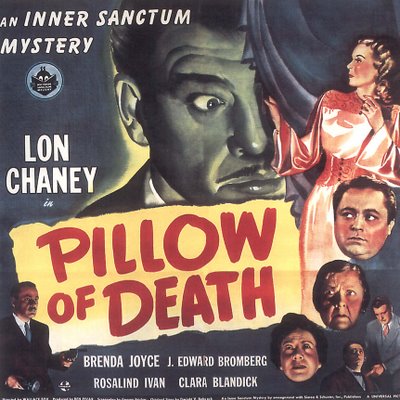

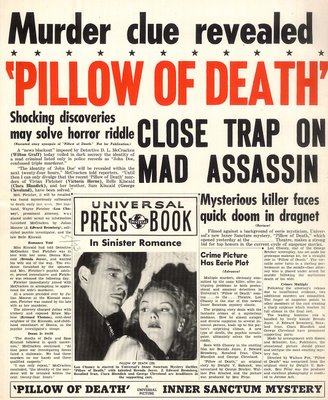

Lon Chaney always struck me as a man to whom promises were made, but seldom kept. He wanted to be a great actor like his father. Universal led him down a garden path with build-ups that suggested roles along the complex lines Lon Sr. had excelled in, but meanwhile, there were serials and westerns to be ground out, and big, beefy Junior seemed made to order for hoisting stuntmen and emptying saloons. A lot of this went on in his private life as well, once Lon realized they weren’t coming through for him. First it was the Phantom Of The Opera remake. That went to Claude Rains (a real actor, as some tactless executive no doubt explained to Lon). Sound stage mentor and adopted big brother Reginald LeBorg said they’d do big things together, but in the meantime, there’s one more Mummy sequel we need to get out of the way. Whatever coinage that remained in Junior's name was being spent in a hurry and Chaney’s alcohol dependence was aging him as well. A Gable mustache effected for the Sanctums was less evocative of Clark than of James Craig, Tom Conway, and a host of other cut-rate leading men. That Chaney face contorted with anxiety does lend a certain conviction to his performance, though we’re more inclined to attribute it to issues arising out of Lon’s troubled relationship with studio employers rather than hackneyed situations confronting him in these. Star Wears Own Clothes In Movie reads a blurb in the Pillow Of Death pressbook, and if that’s to be believed, there's at least reassurance in Chaney's offscreen fashion sense. He’s trim and fit in the Sanctums --- all the more alarming then to see him just a few years later (Manfish, My Favorite Brunette) so aged and disheveled.

Lon Chaney always struck me as a man to whom promises were made, but seldom kept. He wanted to be a great actor like his father. Universal led him down a garden path with build-ups that suggested roles along the complex lines Lon Sr. had excelled in, but meanwhile, there were serials and westerns to be ground out, and big, beefy Junior seemed made to order for hoisting stuntmen and emptying saloons. A lot of this went on in his private life as well, once Lon realized they weren’t coming through for him. First it was the Phantom Of The Opera remake. That went to Claude Rains (a real actor, as some tactless executive no doubt explained to Lon). Sound stage mentor and adopted big brother Reginald LeBorg said they’d do big things together, but in the meantime, there’s one more Mummy sequel we need to get out of the way. Whatever coinage that remained in Junior's name was being spent in a hurry and Chaney’s alcohol dependence was aging him as well. A Gable mustache effected for the Sanctums was less evocative of Clark than of James Craig, Tom Conway, and a host of other cut-rate leading men. That Chaney face contorted with anxiety does lend a certain conviction to his performance, though we’re more inclined to attribute it to issues arising out of Lon’s troubled relationship with studio employers rather than hackneyed situations confronting him in these. Star Wears Own Clothes In Movie reads a blurb in the Pillow Of Death pressbook, and if that’s to be believed, there's at least reassurance in Chaney's offscreen fashion sense. He’s trim and fit in the Sanctums --- all the more alarming then to see him just a few years later (Manfish, My Favorite Brunette) so aged and disheveled.

Unpleasant subject matter is the order of the day among Sanctum mysteries. A faithless wife is beaten to death with a poker in Calling Dr. Death, followed by an acid facial. Naturally, Lon gets tagged for the crime. Dead Man’s Eyes finds thuddingly bad actress Acquanetta switching bottles in Chaney’s cabinet and this time he gives himself the acid facial. A distraught Lon cleaves off his tormentor’s head in Strange Confession and carries it about in a valise. All this unwholesome activity is more implied than depicted, and indeed, the heavy hand of the Code is everywhere in these shows. Chaney wives appear to occupy separate bedrooms. Relationships outside of marriage must be accepted on faith, as physical contact is seldom indicated, despite dialogue suggesting all sorts of libidinous activity on Lon’s part. Others have commented on his unlikely status as catnip for women in the Sanctums, but doggone if the big lug doesn’t acquire a certain oafish charm after four or five of them, so I’m willing to make allowances for that elusive and inscrutable Chaney appeal. Where he really breaks down the fourth wall (sometimes literally!) is when Lon loses his temper. All the Sanctums feature at least one scene where the safety’s off and bestial instincts are turned loose. It’s usually a momentary thing, but always unexpected. Someone will annoy Lon, and he reacts out of all proportion. Players expecting to be merely pushed aside are slung across rooms. Guys who get in Lon’s face come away with crumpled lapels and mild whiplash. Rage is always unconfined when you’re Lon Chaney. Actors must have dreaded onscreen confrontations with him.

Based on what I’ve read, Sanctums were a dumping ground for third-tier studio talent. Producers assigned to them were philistine in taste and boorish in manner. Gin rummy games took precedence over script conferences, Get It Done Quick their only mantra. Astonishing then that the pictures look as handsome as they do, particularly now that we finally have them in beautiful DVD presentations. Again, I'm stunned and delighted at how movie favorites can be reborn when properly delivered in digital format. Universal pictures from the forties have an almost homespun quality. Close your eyes and there’s instant recognition from the title theme’s opening bar. That glittering logo has a way of transporting many of us back to a hundred joyful days and nights in front of the television. Assembly line moviemaking can be a comforting thing as one gets older and tastes regress further toward nostalgia and reassuring familiarity. Why would I sit and look at six admittedly mediocre "B’s" if not to somehow recapture a sensation I felt upon watching them forty years ago? To argue these pictures are "bad" is to miss the point entirely. Certainly for a younger audience they are that and worse --- boring, stupid, banal --- we could rattle off invective for another long paragraph and all the words would fit, but that isn’t what Sanctums are about. Like so many thrillers, mysteries, and monster shows that used to fill TV Guide listings, Sanctums are about isolated moments in childhood and adolescence when school bells weren’t ringing, household chores were done or left undone, and life was a damn sight simpler than it is today.