Rudolph Valentino Gets His Start

My eighth grade class once staged a little program for the school wherein, among other things, we spoofed old-time silent movies. The softest target was, of course, Rudolph Valentino. Everyone young and old could laugh at the Sheik. How did audiences ever taken him seriously? My own participation in the show was half-hearted. I’d only been exposed to Valentino via photos in Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer’s book, The Movies, but something suggested there was more to this actor than the absurd caricature we were kidding so mercilessly. It’s forty years later now, and thanks to remarkable recent discoveries, Rudolph Valentino may finally get his belated due. The real surprise within these buried treasures is how good he was from the very beginning. A look at The Married Virgin, thought lost until 1995, reveals an actor so assured as to single handedly transform not only his character, but also the story itself. Cast as a fortune-hunting scoundrel, Valentino brings nuance and sympathy to a stock role anyone else would have played along standard villain lines. You know an actor’s good when he keeps you wondering how the show is going to turn out, even when you know all along how it’s got to turn out. Valentino spent three or so years transcending stereotypes and defeating efforts at typecasting. I’d read of swarthy gigolos he played in those early films, but that seems too simple a designation. Rudy’s scoundrels were above simple acts of perfidy. His performances work against cliches inherent in these stories and often overcome them. There are layers of yearning and complexity reflecting an offscreen life in close parallel with rogues he impersonates. His own dalliances with scandal and crime prepared Valentino for parts like these. Perhaps Rudy was dramatizing incidents experienced on the fringes of a New York society he’d inhabited just a couple of years before. In those early days of the twentieth century, a man could still run away from an unsavory past and start anew…

Valentino never came of peasant stock, as some biographers would maintain. If anything, he was overindulged as a boy. The father’s death when Rudy was 11 left him without direction or discipline, and a lifestyle given over to indolence and sloth seemed to loom before him. Rudy wanted to amount to something, and toward that end, talked his mother into staking passage to New York at the age of 18. Picking up English where he could, it would become the fourth language he’d master. Rudy liked the high life, and was quite the pretender within a social structure where appearance was everything. He made friends easily. Hanging around cabarets feigning wealth and status was all well and good until the money ran out, then it was odd and often menial jobs, plus occasional nights sleeping on a park bench. Rudy had a way with the latest dances and made himself available for afternoon tango teas where rich and idle women paid for the titillation of swirls around the floor with handsome, exotic strangers. People liked him and wanted to help out, even when he screwed things up. Sometimes the blunders arose from his own good intentions. An effort to assist a society doyen in shedding an unwanted husband made powerful enemies. Rudy served as a witness against the woman’s straying spouse and the man sought revenge. A charge of white slaving lodged against Valentino in 1916 was probably a frame, but it consigned him to The Tombs (New York’s notorious lock-up) for several days and tarnished him among gentlefolk once friends. The finishing touch came when Valentino's divorcee consort went after her estranged mate with a pistol and emptied the chamber into his head. It was time for Rudy to take a trip.

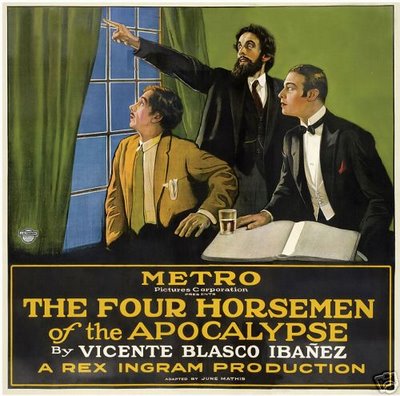

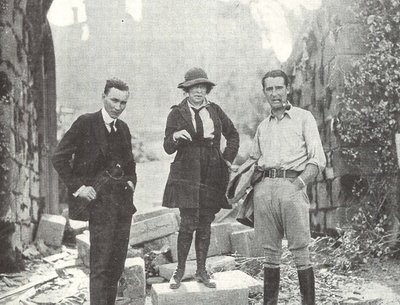

Upon arriving in California, Valentino used his dancing skills to promote a stage career. Success in New York ballrooms might have led to a renewal of those pursuits in Los Angeles, but Valentino now shunned the unsavory occupation of dance partner for hire, itself only one step removed from dreaded gigolo status. Movies were the goal he sought, and again, people went out of their way to lend a hand. Big names like Viola Dana, Gloria Swanson, and the Gish sisters were early boosters, but none took notice of Rudy as lothario or swoon artist. This was one performer who would epitomize sex on screen, while assuming a near polar opposite image off. It really was all just an act. Those lounge lizards he portrayed mirrored the pose Valentino had to maintain for his own survival, but being close to roles he was often obliged to assume in life, they seemed particularly degrading to him now. He was set upon breaking free of these when writer-producer June Mathis caught his seducer act in Eyes Of Youth and committed herself to promoting him for The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse, a proposed roadshow special for Metro. Mathis was a capable, but homely, sort --- maybe Rudy was her idea of a perfect lover, but she was his idea of a perfect big sister, and that was something he really needed at this career juncture. For $350 a week (up from the $100 he got for doing The Delicious Little Devil in 1919), Valentino got the lead in The Four Horsemen, but had to provide his own costumes. The elegant wardrobe he wore throughout was courtesy Rudy’s own New York tailor, and it would take the actor two years to pay off the tab for those twenty-five custom suits.

There’d been a marriage, to an actress named Jean Acker. She locked him out of the bridal chamber and vows were never consummated. Seems Jean neglected to tell Rudy she was a lesbian. This wouldn’t be his last dance around that maypole. The union was dissolved before he got into big chips, though Valentino would forever seem incapable of making it work with women in any capacity other than friend. He had a generous bounty of those, plus a coterie of male pals that shared his interest in fast cars and motorcycles. Few in the industry were as well liked, and after The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse, none so much in demand. What was his performance here but a distillation of promise shown in the gigolo ghetto from which he’d finally been sprung? It’s a shame so many of those early films remain lost, for I suspect there’s all sorts of good work that would anticipate the riveting performance he gives in The Four Horsemen. For a picture made in 1921, it still plays remarkably modern, and Valentino is at all times natural and convincing in the lead. The big tango sequence represents his grand entrance, and indeed, history tells us this was the moment his star was truly launched. For the five short years he enjoyed as a major name, Valentino would never again be in a picture this big, and certainly not one so successful. The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse appears from time to time on TCM. It’s a long show, but an epic one, and well worth 131 minutes of anyone’s time.

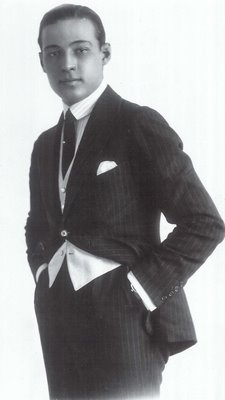

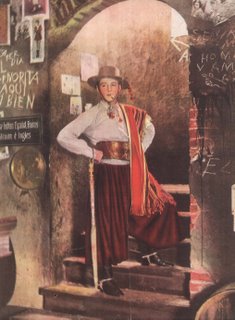

Photo Captions

Early Portrait --- Rudolph Valentino

Valentino In The Married Virgin (1918)

With Mae Murray in The Delicious Little Devil (1919)

Valentino in Eyes Of Youth (1919)

Portrait of Jean Acker, Valentino's first wife

Valentino as Julio in The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse (1921)

Six-Sheet Poster for The Four Horsemen

Cameraman John Seitz, writer/producer June Mathis, and director Rex Ingram on location for The Four Horsemen

Valentino performs his famous tango in The Four Horsemen

With Alice Terry in The Four Horsemen

A great website devoted to Rudolph Valentino can be found HERE.