The traumatizing prospect of a Loopy De Loop cartoon being shown theatrically would seem a near-impossibility today, yet such a thing did happen when Columbia announced its glittering roster of short subjects for the 1967-68 season. I hesitate to dwell upon the horrific bill of fare on studio schedules during that benighted year, a truly frightful period for theatre-goers. 1967-68 heard the dying gasp of old-time exhibition --- showmen and distributors still clinging to antiquated notions that short subjects could bring customers back to theatres. Newsreels had finally disappeared with the closure of Universal and Metro’s units, and cartoons were being farmed out to independent producers or temporary hirelings whose sole concern was to make them cheap and quick. I can still recall the feeling of dread evoked by opening fanfares for sixties cartoons. Knowing the vintage ones on TV were infinitely better, we’d have better been spared Pink Panther or Woody Woodpecker intrusions into otherwise desirable programs. I was shocked to learn that there were over 300 short subjects released in 1967-68. This sounds very much like the motion picture equivalent of as many shots in the belly they give when you're bitten by a rabid dog (okay, maybe 300's a bit of an exxageration, but it was at least 20). I can’t imagine their being shown to any audience today other than recalcitrant prisoners of war from whom one is trying to extract classified information.

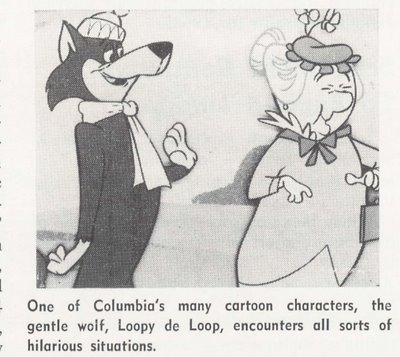

As you’ll note in the captioned still, "the gentle wolf" Loopy De Loop was Columbia’s star attraction for the season. Hanna-Barbera had been commissioned by the studio to produce these cartoons for theatres. An act of colossal effrontery, you might say, considering the fact we’d been getting all of H&B’s output for free on the home screen since, what, 1959? Was that the year Huck Hound first appeared? Anyway, things had deteriorated far enough by the mid-sixties that I for one could no longer tell these Photostatic characters apart. There was a Hokey Wolf, as I recall. How did he differ from Loopy? No doubt they were both gentle, befitting pabulum diets we were getting from TV cartoons by way of vigilant cereal and toy sponsors determined not to frighten children or offend their parents. Other than minor species differentials, what indeed was the distinction between Wally Gator, Lippy Lion, Magilla Gorilla, and The Hillbilly Bears? These were dark days for animation. It’s a wonder our generation survived it. Never mind the damage sustained by Viet Nam and the drug culture. It was these cartoons that consigned many of us to a lifetime of sloth and indirection. Hanna and Barbera, you were great with Tom and Jerry, but you still have much to answer for!

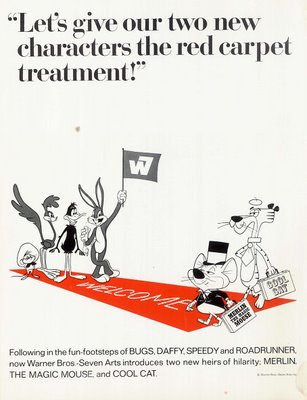

One can overlook Universal. Those Woodpeckers were never much good to begin with, let alone Chilly Willy and the rest of the Lantz menagerie, but Warners! How could they? By this time, they’d even junked the tunnel opening for their cartoons. Sacrilege! Note Bugs Bunny and his welcome banner for the two arriving nondescripts. Was there ever an uglier logo than that of Warner Bros./Seven Arts? The idea that it would now open a WB cartoon is a stench in the nostrils of Heaven. I’ll not speculate as to who Cool Cat and Merlin The Magic Mouse are. I’ve not seen any of their adventures, hope never to, have no idea how many cartoons they appeared in, and refuse to look it up. Am I too harsh? Are they undiscovered classics? Merlin looks sorta like a Chuck Jones creation in this trade ad, while Cool looks like a H&B clone --- but wait, Top Cat was cool too, and he came first (and for free), so why pay to see this guy? I wonder if any of the Cartoon Network offshoots run these late Warner shorts. I do know what some of them cost to make. On the high end, there was Bunny and Claude, a "special", which had a negative cost of $35,360. Chimp and Z was $35,065. Average cost for the 1967-68 group was a lean $26,704. This was only a couple thousand more than they were spending in the early fifties, but in those days, of course, you got a lot more for the money (Duck Dodgers was made for $24,022 in 1953).

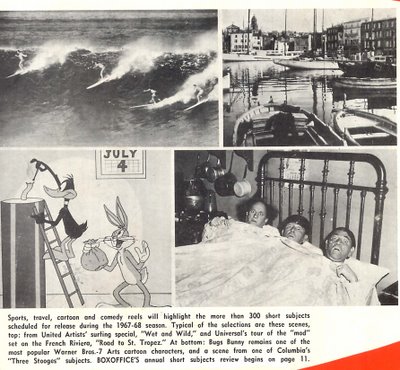

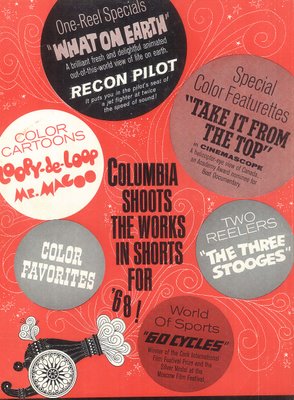

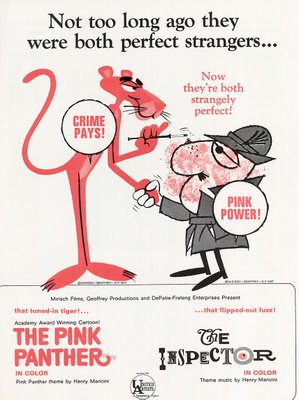

MGM promised eight new Tom and Jerry cartoons for 1967-68, along with twelve "Gold Medal" subjects (re-issues). Average cost for a T&J that year was $32,603. The total cost for the season was $260,826, but rentals only added up to $199,386. The Tom and Jerry series was now a losing proposition theatrically, but television revenues from the cartoons would make up the loss. The twelve re-issues were more lucrative. Total rentals for these were $179,833, and this was clear profit, beyond prints and distribution cost. Car Of Tomorrow was making its third go-round for rentals of $15,657 --- it had gotten over $135,000 total since initial release in 1951. Bad as these new Tom and Jerrys were, Metro at least knew how to market them. While other cartoon libraries were being ground up in syndication, the T&J series enjoyed network play throughout the sixties and much of the seventies. These sales helped MGM get back that money they’d lost in the theatres. United Artists, meanwhile, had over a dozen Pink Panther cartoons in the pipeline, along with the Inspector series. The formulaic structure of these was rigid, if not calcified. I used to take seven minutes to linger around the snack bar and check out posters in the lobby whenever one would start. The live action shorts mentioned in these ads were about as stimulating as filmstrips at school, notwithstanding the fact that we were watching them on our own time, and paying an admission for the dubious privilege of doing so. Our suffering wouldn’t last much longer, as short subjects disappeared altogether within a few years. No frills exhibition would soon become the norm. If there is a modern equivalent of shorts, it may well be the endless commercials that delay the start of contemporary movies by as much as twenty minutes.