Monday Glamour Starter --- Mary Miles Minter

Monday Glamour Starter --- Mary Miles MinterMary Miles Minter was cursed from the day her evil mother committed an unholy act that surely consigned the two of them to eternal damnation. More about that in a minute. First, I’d address the question of why an actress who disappeared from the screen in 1923 should qualify as a Greenbriar Glamour Starter. Was she good? Nobody really knows. They probably never will, because most of the films have long since gone to nitrate heaven. If we hear of Mary Miles Minter nowadays, it’s probably in connection with an unsolved Hollywood murder she was mixed up in. Frankly, I’m writing about her because I think she’s kinda hot --- a sexy Mary Pickford (after whom her career was patterned) who seems to have had a refreshingly robust libido beneath those ribbons and pinafores. Pickford always looked shapeless to me, forever doing the take charge thing as she dragged orphans out of gator-infested swamps. She’ll never make the Glamour Starter cut, I fear, unless they come up with some footage to redeem that cold and sexless image I have of her. Not so Mary Miles Minter. Her life ran the gamut from Hell to stardom, which was Hell itself for Mary, then back to just plain Hell, as she went the Norma Desmond/Baby Jane route so beloved of writers anxious to shock and titillate their editors and readers. I pledge to remain above such lazy devices --- Mary was not Norma --- Norma wanted back in, Mary never did --- Baby Jane maybe, but more about that later as well.

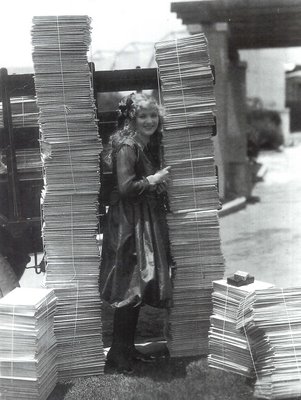

Juliet Reilly was her real name. That got changed when her diabolical mother packed off Juliet and her sister for New York and the stage. There was a father once, but he’d been jettisoned after raising objections over Charlotte’s plans for their daughters. Even among ultra-aggressive stage mothers, Charlotte was a bitter pill. She once advised Juliet to "be powerful, even if you have to walk across the graves of others to get it!" Well, that’s exactly what they ended up doing when the Gerry Society (a group set up to enforce child labor laws) expelled ten year old Juliet from her long running stage hit, The Littlest Rebel, where she had the title role. Seems Charlotte had a sister and a niece who’d died seven years previous --- mother and daughter had both consumed apple cider laced with lethal snake venom. Now, I can’t let that last part go by without comment, like for instance, how the deuce would snake venom wind up in a barrel of apple cider?? Was this somebody’s idea of a flavor enhancement? They sure had some radical ways of checking out during the teens. But back to Charlotte’s niece. Her name was Marie Miles Minter. She was only ten when she died. In those days before Social Security numbers, it wasn’t that difficult to purloin someone else’s identity. Charlotte stole the dead child’s birth certificate and did just that, assigning Marie’s name to Juliet (with the slight modification of "Marie" to "Mary") and "introducing" the now seventeen-year old Mary Miles Minter as the new star of The Littlest Rebel (there’s gotta be a real pay-off in perdition for somebody who would do a thing like this). Movie offers followed, and they prospered. Paramount would eventually dangle $1.3 million for a twenty-picture commitment (here’s Mary with two massive piles of fan photos ready to go out in the mail). Charlotte spent the money as fast as Mary could earn it (that’s become almost a parable around here, hasn’t it?). The sister, Margaret, seethed with jealousy (like Blanche Hudson?). Mother clearly missed her calling as a white slaver, for she had poor Mary down to a minute schedule as efficient as any of the streetcar companies, so much so as to make the teenager positively loathe her star status and obligations. Was this, then, the dead girl’s curse? Had the real Marie Miles Minter, whose name and identity they’d stolen, come back to collect? If so, she had a large account, because Mary, her mother, and her sister, would pay … and pay … and pay.

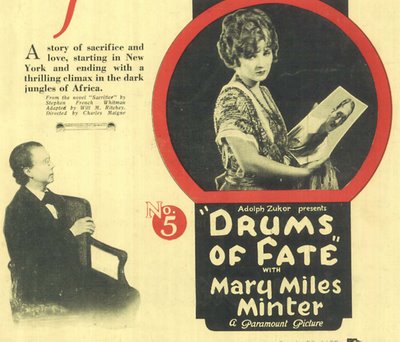

William Desmond Taylor was a bon vivant fifty-year old director with a cultured manner and apparent pedigree. Truth is he was a rotter who’d abandoned his family back in New York years before (guys did that a lot back then) and had since barnstormed the country in alternating roles as gold prospector, hotel night clerk, and finally, a berth for which he was ideally suited, acting. The grass widow back home spotted him on a Nickelodeon screen and the jig was up. By then, Taylor (his seventh adopted alias) had taken up the megaphone and was now directing Mary Miles Minter, a winsome lass who missed her own daddy what got left behind and tagged Bill for a surrogate (here are two pics of Bill with Mary --- Bill’s holding the leaf branch in the three-shot). Contemporary accounts in defense of the old fox vowed her advances were rebuffed, but methinks his "Go away, little girl" entreaties were half-hearted at best, cause pretty soon twenty-year old Mary was pitching camp in front of Bill’s fire. Charlotte saw red in any case. She’d already threatened leading man James Kirkwood with a shootin’ iron after the actor conducted an impromptu, and very private "wedding" ceremony with Mary deep in the woodland location of their recent co-starring film. Jimmy had convinced Minter they were "married in the eyes of God" and managed to square away the consummation before the two were even missed by an inattentive camera crew. Charlotte was, if anything, even more determined to keep her investment away from Taylor. By February 1922, the thing had come to a boil, and on the night of the eleventh, Bill was found on the floor of his bungalow with a bullet in his back. Police dicks found Mary’s love letters hidden in the deceased’s riding boots (nice touch, Bill) and the star was brought in for questioning. Charlotte was the one they should have grilled, and indeed they would, but Mary took the brunt of bad publicity, and was just waiting out her twenty-first birthday anyway so she could dump Mom and the whole dirty star racket. Myth has it that Taylor’s death wrecked her career, but Paramount used Minter in six features following the incident (several of them solid hits), and wanted her for The Covered Wagon, but instead bought out the contract at Charlotte’s insistence. After 1923, Mary Miles Minter would never stand in front of a camera again.

The longer the Taylor case went unsolved the worse it smelled. Mary stayed in the headlines by foolishly brandishing her ongoing romantic obsession with the dead man, boasting of how she’d gone by the morgue to give him a goodbye kiss. Rumors were rife, and suspects plentiful. Had Bill been offed by drug pushers? Each wild speculation beget more, as Mary, Charlotte, and Margaret sued and counter-sued one another through decades of bitter exchange. Mary said Charlotte had looted the million she’d made in movies. Charlotte tried to have Margaret put into a mental institution. Margaret tried to pin the Taylor murder on Charlotte. Charlotte sued a guy for stealing the money she had stolen from Mary. Round and round it went. Mary got round too, ballooning up to 300 pounds in an effort to make up for that starvation diet she’d been on when she was a star. Sister Margaret died a hopeless alcoholic in 1939, and sainted mother Charlotte departed in 1957 --- or did she? Neighbors reported sightings into the sixties, and swore a now reclusive Mary had the old woman sequestered upstairs. Not likely though, as Mary actually wed later in that same year, and had a lucrative second career in real estate. Film historian David Bradley took some of Mary’s old films over to her house for a show, but she was largely indifferent to them. A few times she threatened to sue producers and writers of would-be Taylor exposes and dramatizations (one of them Rod Serling), but those usually fizzled after the obligatory "Where Is She Now" stories ran their course. Silent director King Vidor tried to get a coherent interview out of her in the late sixties, but she was way gone by then. Fans could still get autographs by mail, however, and she’d been the last surviving principal in the Taylor case for some time when she died in 1984 at the age of eighty-two.