Judgment At Nuremberg

One thing that always diminishes the suspense for me in a Spencer Tracy picture is the fact that Spence always gets to be right --- especially in those later ones when he’s an old man (albeit one in his sixties who looks to be in his eighties), and gets all the zinger lines that invariably end arguments in his favor. That happens a lot in Judgment At Nuremberg. People are constantly coming at Spence with well reasoned positions that seem perfectly sensible --- only to forget they're dealing with Spencer Tracy, and Spence is never wrong. He’s the font of wisdom for every occasion, and I don’t wonder that a little of that bled off-screen, as they say Tracy didn’t like contradictions there either. It’s really a good thing he was such a great actor, cause he sure was a truculent sort from everything I’ve read. Long-suffering columnist Bob Thomas thought he and Spence were buddies when he visited the Nuremberg soundstage, but all Bob got for his trouble was a sound cussing and a tail-between-legs exit off the set. Seems the hapless scribe had made the mistake of joshing with that intensely serious ac-tor Burt Lancaster, inquiring as to which among the all-star cast would "out-ham" the rest. Affronted Burt took the matter to Spence and the chill set in. I was actually thinking of chills when I observed those opening scenes of Tracy touring the Nuremberg locations. He’s wearing an overcoat, as are a number of extras and townsfolk in the distance, and I wondered momentarily if the notoriously fragile Tracy might get pneumonia on those damp streets. What if he’d been laid low after the first two or three weeks? Stanley Kramer and United Artists would have had to file an insurance claim, then replace their lead actor. It would have been Solomon and Sheba all over again. Well, clearly I wasn’t into the story of J.A.N. at this point --- I was thinking about movie stars --- but what to do, when there were so many more of them to come?

We’re not a reel into this three-hour monster when the door opens and young Bill Shatner walks in. You know what? He’s good in this show --- and if I ever meet Bill, I’m going to tell him so --- and he’ll thank me for not jabbering on about all his Star Tricks, which has got to be the most boooring subject in the world for him (sure is for me). Neophyte Bill was ringside for a thespic showdown where each contestant made their way up to that witness stand to be sworn in by his character, who then sits quietly by as they shout, blubber, collapse, twitch, and tremble their way through the most extraordinary series of nakedly determined bids for an Academy Award this viewer has ever seen. A number of them would be nominated, but only Maximillian Schell would win. Max got special recognition for Best Supporting Performance Where Everyone Shouts A Lot. Jim Cagney ran them all a close second for One, Two, Three, but Academy voters tend to prefer dramatic shouting over merely comedic exertions, so a disillusioned Jim retired to his farm and didn’t make another movie for twenty years. You know you’re in trouble with Judgment At Nuremberg when opposing sides start raising voices from the trial's very outset. I don’t know what kind of direction Dick Widmark got, but he comes in roaring like a lion, which is all well and good, I suppose, but with three hours left in the marathon, what do you do for a climax?

That tragic wreck of a once fantastic actor Montgomery Clift is frankly exploited here as his walking wounded role calls up any number of disturbing parallels with the devastation of Clift’s own life. 1961 audiences had to be shocked by the horrific effect of those few years since he was the most promising young romantic star in movies. Watching him struggle through what amounts to an extended cameo is a painful thing to witness, especially if memories of Red River and A Place In The Sun are fresh in the mind. The long speeches were an impossibility by this time, so Spence lent a hand by advising Monty to wing it as best he could and direct his "testimony" to Judge Tracy. Kinder critics lauded Clift’s interpretation, but this may have been one time when an actor got a little too close to the truth. After one more disastrous lead (Freud), Montgomery Clift was pretty much through in the business. Judgment At Nuremberg came during the third act for Judy Garland as well. Her character takes the stand twice, and you know they’re just warming us up with that first round because Judy’s all subdued and that, of course, is not in keeping with the histrionic powderkegs they’ve been lighting so far in this movie. Sure enough, when she gets up there the second time, all hell breaks loose with an emotional breakdown that again crosses the line between artifice and reality. Two great "confessional" performances, but neither Clift nor Garland would really benefit from them. Even wily Burt Lancaster seems defeated by a miscast old-man impersonation where his German accent wavers and the pressure to bellow out his long-awaited speech is just too great for Burt to resist. The most effective performances are ironically those of supporting players, and it’s nice to see veterans like Ray Teal and Virginia Christine lending understated expertise to an enterprise that can sure use it.

That tragic wreck of a once fantastic actor Montgomery Clift is frankly exploited here as his walking wounded role calls up any number of disturbing parallels with the devastation of Clift’s own life. 1961 audiences had to be shocked by the horrific effect of those few years since he was the most promising young romantic star in movies. Watching him struggle through what amounts to an extended cameo is a painful thing to witness, especially if memories of Red River and A Place In The Sun are fresh in the mind. The long speeches were an impossibility by this time, so Spence lent a hand by advising Monty to wing it as best he could and direct his "testimony" to Judge Tracy. Kinder critics lauded Clift’s interpretation, but this may have been one time when an actor got a little too close to the truth. After one more disastrous lead (Freud), Montgomery Clift was pretty much through in the business. Judgment At Nuremberg came during the third act for Judy Garland as well. Her character takes the stand twice, and you know they’re just warming us up with that first round because Judy’s all subdued and that, of course, is not in keeping with the histrionic powderkegs they’ve been lighting so far in this movie. Sure enough, when she gets up there the second time, all hell breaks loose with an emotional breakdown that again crosses the line between artifice and reality. Two great "confessional" performances, but neither Clift nor Garland would really benefit from them. Even wily Burt Lancaster seems defeated by a miscast old-man impersonation where his German accent wavers and the pressure to bellow out his long-awaited speech is just too great for Burt to resist. The most effective performances are ironically those of supporting players, and it’s nice to see veterans like Ray Teal and Virginia Christine lending understated expertise to an enterprise that can sure use it.

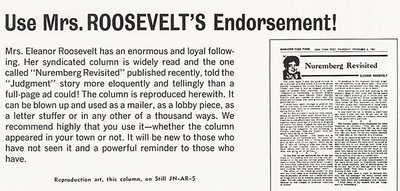

Old-fashioned ballys for this kind of show would have been frowned upon, so exhibitors were advised to go the dignified route. No doubt a lot of thoughtful readers would have acted on Eleanor Roosevelt’s endorsement and bought a ticket, but how many thoughtful readers were still going to movies by 1961, a year in which The Absent-Minded Professor and The World Of Suzie Wong were counted among the most popular? I like that telephone display, but notice that showmen were advised to "rig up" one themselves, and by the looks of this rather elaborate model, that would have been a pretty tall order for the smaller houses (my sister had one of those Princess phones in 1961, by the way, and they were sure enough neat). The stills give us a glimpse of most of the names we mentioned earlier, though it’s worth noting Marlene Dietrich’s rather pinched expression in this shot with Spencer Tracy. She’d had (another) face-lift just before production, and the usual lighting tricks she demanded would betray her this time, as they’d cruelly emphasize, rather than conceal, the lack of mobility in her facial features. This final candid was taken at the premiere of Judgment At Nuremberg in Berlin, where a hostile German press merely exacerbated the already bizarre behavior of Montgomery Clift (bearded here for his role in Freud), who, according to one observer, "showed up stoned and drunk out of his mind, jumping on Spence’s back." Things got worse when Monty crawled on his hands and knees between the aisles, and "screamed all sorts of crazy things," causing Tracy to flee from the auditorium. Judgment At Nuremberg ended up with what had to be a disappointing $3.9 million in domestic rentals, with an additional $2.2 foreign, for a worldwide total of $6.1 million.