Paramounts On Parade

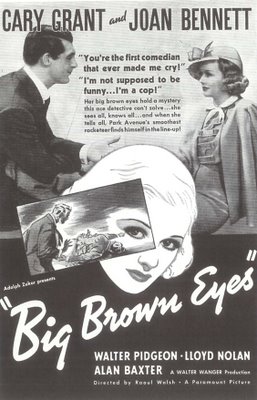

It was sheer coincidence guiding my path toward four Paramount shows this week, that plus recent DVD releases of several I’d been curious about, and as I’d promised myself to just watch movies without feeling compelled to write about them, here I am, of course, writing about them. The earliest was Big Brown Eyes, one of five Cary Grant Paramounts offered up by Universal in its new Screen Legends line (hope these continue). This one substitutes generic wise-cracking for double-entendres we’d prefer, but as Big Brown Eyes was a 1936 release, you know everyone’s going to be wearing Code-cuffs. You could call this a time-waster and offhand name two dozen better Cary Grant films (same for director Raoul Walsh). Any show set in an upscale mid-thirties deco barber shop gets an automatic pass in my book, but I was really put off by the plot device involving a baby shot and killed in its carriage. Now when is a thing like this ever necessary? Had I known of it in advance, I wouldn’t have watched. Movies so slight as this are notable only for details, those things unexpected and perhaps unintended. My impression of major studios as virtual sweatshops was confirmed here, as even fastidious Grant is revealed to be wearing a drenched shirt when alighting from his barber chair in the opening reel, and there’s surprisingly explicit gangland mayhem involving Lloyd Nolan, Alan Baxter, and Henry Brandon. Big Brown Eyes came toward the end of Cary Grant’s cut-and-paste leading man period, and there are glimpses of the accomplished farceur to come, but for the life of me, I can’t remember just what or who he plays in this, even within days of having seen it. Was it police detective, crime-busting reporter, or playboy sleuth? Just pick a number when you sit down to watch one of these, but don’t imagine you’ll recall much about the experience later.

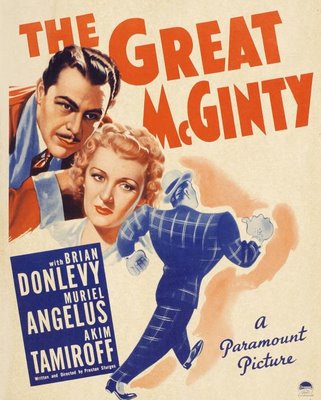

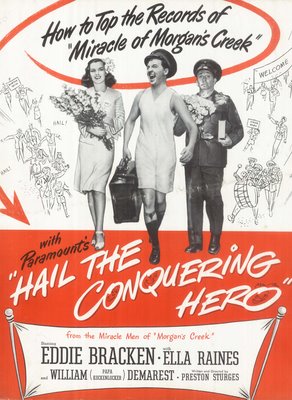

Preston Sturges for me is like a too loud guest at the dinner table. He writes well, but must his players shout it all out? Universal has released seven of the Paramount comedies, and I watched The Great McGinty and Hail The Conquering Hero this week. I guess you could say the first one suggested promise fulfilled by the second. McGinty would have seemed fresher in 1940 when its kind of realist viewpoint was less common in movies, though pre-codes such as The Dark Horse and Lawyer Man routinely skewered the political process and in retrospect seem funnier than McGinty. Sturges was hamstrung by the Code like everyone else and built his reputation by seeming to flaunt restrictions meekly observed by others. He’d have been happier peaking during the early thirties when they’d permit more teeth for his kind of bite. As it is, Sturges just got louder to express his frustration, first with Code shackles, then with unsympathetic Paramount bosses constantly reigning him in. There must have been something in his personality that invited interference. Was it his eccentric mode of dress? --- those silly hats he wore on the set? I understand he wasn’t above belittling perceived intellectual inferiors. Maybe some of them got tired of that and banded together to bring him down. Happens all the time in the workplace. Smart guys often finish last precisely because of it. Even today, there’s a challenge at the front end of every Sturges viewing. Are you bright enough to get what he’s offering, or missing humor operating several levels above your capacity? That seemed to be the burning question of Unfaithfully Yours, and it’s no coincidence this one came at burnout point for the director. Big stars work best with Sturges because they bring discipline and restraint to otherwise chaotic proceedings. Barbara Stanwyck, Henry Fonda, Joel McCrea, and Claudette Colbert are stabilizing influences in The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels, and The Palm Beach Story, probably the only three Sturges features I’d try springing on a general audience. When he turns loose that gallery of character support in The Miracle Of Morgan’s Creek and Hail the Conquering Hero, it’s time to break out earmuffs and headache tablets. Who but Sturges would back up Franklin Pangborn’s cacophony with multiple brass bands? Everyone hollers to get above it. Noise drowns out the wit, but I have to assume Sturges encouraged this. World War II acted like a massive speed pill for American movies, from Abbott and Costello, to overblown musicals, Bette Davis melodramas --- even Frankenstein met The Wolf Man to quicken the pace, so you can’t tag Sturges alone for ramping things up too high. As Miracle and Hero were major hits, he obviously gauged the pulse of 40's viewers, which makes his artistic and commercial collapse all the more puzzling, another of those directors whose life, in the end, may be more interesting than his movies.

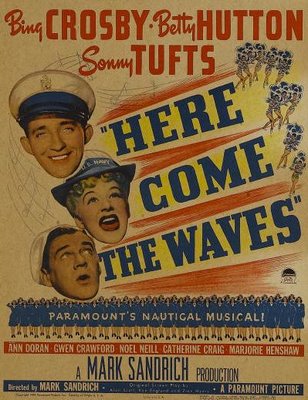

On the topic of restraint, and lack of it, there are two Betty Huttons offered up in Here Come The Waves, a near perfect time capsule of formulas that worked ideally then, but seem remote, if not peculiar, now. Imagine one of those Abbott and Costello service comedies with Bing Crosby and Sonny Tufts instead of Bud and Lou … then sprinkle liberally with thousand dollar bills as opposed to sawbucks invested by Universal. Orson Welles could have given us three more masterpieces at RKO with money spent here --- Val Lewton a whole season. For something so utterly forgotten today, it’s remarkable to look back and realize this was the very sort of show lining them blocks around three-thousand seat palaces in 1944, with customer satisfaction virtually assured, owing to Crosby’s having just come off Going My Way, and Hutton’s being the voice braying out of every jukebox. Here Come The Waves is fun for insights it provides as to what rang the bell with movie-going folk back then. Bing plays a movie star/bobby-sox idol and navy recruit (at age forty-one) whose effect on teen patrons approximates that of newcomer Frank Sinatra. I found myself wondering if by-then veteran Crosby’s impact was so overpowering as depicted here, my point of reference being the Warners cartoon Swooner Crooner, made the same year, wherein the animated Bing’s fervid following seems limited to hens of egg-bearing maturity. Did his singing still lay young girls in the aisle by 1944? Here Come The Waves implies it did. Sonny Tuft’s appeal, far less measurable, vividly illustrates what happens when 4-F talents are left behind to do the work of 1-A stars. He comes across like a non-pro that got into movies for having sent in the requisite number of box tops. There can’t be any explanation for his career other than blind, fool, random luck. Here Come The Waves was directed by Mark Sandrich. He was the ace technician who promised George Reeves a mighty push as soon as the war ended (but died before the pledge could be honored). I kept thinking that if George hadn’t gone into the service, perhaps he’d be filling Sonny’s part, with the whole enterprise being infinitely better for it.

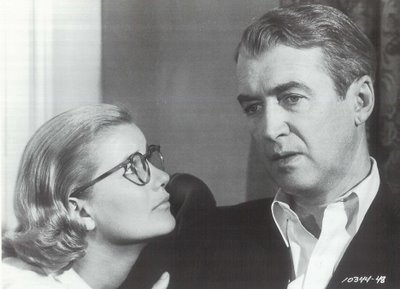

My renewed acquaintance with Vertigo after ten years had a startling effect. Why did it take a lifetime to recognize the greatness of this Hitchcock? Are there movies so rich, so complex, that they should require most of one’s own experience to grow into them? Previous encounters with Vertigo had been tempered with disappointment. Each time, I’d find myself hoping this would be the breakthrough, that all of what they tried to explain in laudatory books and essays would become clear to me. For this boy of sixteen, Vertigo had not the flair of a Rear Window or North By Northwest. 1971 would be the last sighting until 16mm collecting permitted another go-round in the eighties. This time, I’d at least embrace Herrmann’s score and certain bravura highlights, if only the story worked better. It seemed Hitchcock erred in revealing the murder plot too soon, for now what was left to surprise us at the finish? I’ve read this was a bone of contention in 1958 as well, and indeed some at Paramount wanted prints reshuffled to withhold the twist until the end. At this embarrassingly late date, I think I understand. For Hitchcock, the real suspense lay in whether Kim Novak’s "Judy" character would allow Scottie to re-make her as Madeleine, and run the risk of exposing the scheme in which she’d participated. The contrivance of Gavin Elster’s having set up the whole thing just to dispose of his wife was just that --- a gimmick --- which Hitchcock utilized in order to deal with issues more important to him. Why not go ahead and put the audience in the know so they can focus on the real story, which is James Stewart’s obsession and his doomed love for this woman. I think the thing that puts people off on Vertigo is less its lack of humor and familiar Hitchcock thrills than the fact it deals with the sort of personality most viewers have a difficult time identifying with. Obsessive romantics are hard enough selling to other obsessive romantics, let alone to that majority of pragmatic film-goers baffled by characters so willing to plunge themselves into such ill-advised and hopeless quests. I’ve heard Hitchcock fans express great impatience with Scottie Ferguson. Why couldn’t he be more like L.B. Jefferies or Roger Thornhill? Patrons have always preferred doers to dreamers, and that may be the essential conflict between Vertigo and much of its audience.