Greta Garbo --- Part Two

Greta Garbo --- Part TwoIt wouldn’t do for other players to take up Garbo’s distant ways, as there was water but for few at the anti-stardom well (folks never liked their idols standoffish). G.G. drew from that successfully from almost the beginning, but how does that solitary image reconcile with an allegedly torrid laison with John Gilbert? Could there have been more publicity than truth in their off-screen relationship? It’s just possible Garbo relented for once and sought the press she’d receive for linking with Jack, and Metro would certainly have been complicit, but what of poor Gilbert? Was he played for a chump here? How passionate could this woman have been for any man, when all evidence points to a continuing preference for Mimi back home, and the delights to be had upon their forthcoming Swedish reunion? It seems Gilbert was the only one who bought into the notion of a Great Love, just like in the movies, for that’s the alternate reality Jack lived in most of his adult life. A newly empowered Garbo was meantime rattling studio chains with walkout threats (she wasn’t kidding either), and unilateral scheduling which found her Euro-bound before retakes could be completed on her latest MGM show. No longer could Mayer intimidate with dire warnings of suspension and talk of disobedience and insubordination (typical verbal fallbacks in previous Garbo addressed memos). She merely got on the boat and said she’d be back for $5000 a week … no less. Never was such power so vested in a contract player. Metro would make medicine or feel the wrath of exhibitors. Flesh and The Devil had scored $466,000 in profits, The Divine Woman $354,000 --- Garbo was, along with Chaney, the most consistent profit-getter on the lot.

Established silent names made handy cannon fodder for the talkie revolution. Headliners of once solid standing were now so much carrion for the crows. Foreign accents were deadly. Emil Jannings split altogether to avoid embarrassment. Vilma Banky flipped pancakes (!) in her first audion for Goldwyn (This Is Heaven), but Hungarian leading ladies were a hard enough sell in Hungary, let alone here, so Banky retired. Precipitous was a word that might apply to these sooners --- busting out of the gate in early 1929 exposed any number of limitations, and MGM was loathe to feed Garbo into such a career chipper. Her final silent would also be the studio’s last (The Kiss), and that didn’t open until November of 1929. By then, virtually all of Metro’s femme leads had spoken. There was much at stake with Anna Christie. Uncertainty as to its prospects, especially in view of what had happened with so many others, must have been considerable. Reassuring was the fact that MGM’s prowess with sound had gotten Shearer and Crawford over the hump, but even their initial sound numbers couldn’t touch Garbo’s --- Anna Christie took $576,000 in profits to The Trial Of Mary Dugan’s $421,000 and Untamed’s $508,000. The formula for Garbo was rigid, if not ossified. Leading men were non-threatening (though Clark Gable was an alarming one-shot exception). Gavin Gordon, (a young) Robert Montgomery, and (an intimidated) Melvyn Douglas would serve nicely in keeping all eyes upon Greta, for hers was a fragile image after all, and it wouldn’t do to mis-match this actress with too-dynamic leading men (but wouldn’t it be great to see Garbo paired off with Cagney or Warren William in a Warners pre-code?).

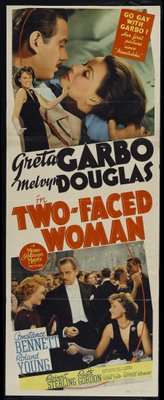

Hollywood and Sweden remained on competing sides of Garbo’s Ping-Pong table. Metro panicked whenever she boarded ship, always fearful she may not come back. Could that explain the two pic a year contract signed in 1933 --- at $250,000 per show? Obviously, these would be specials. Queen Christina was co-penned by one Salka Viertel, whose Svengali influence ensnared a now art-for-art’s sake Garbo. Viewers began noticing a morose overcast in both Garbo and her chosen vehicles. Anna Karenina was good, if unnecessary, especially as she’d done the story before, and with a more effective leading man (Gilbert). Conquest in 1936 would be Garbo’s baptism in red ink. The loss was a stunning 1.3 million, the worst hit Metro took that decade. There were pretenders. Marlene Dietrich was Paramount’s copy-cat, and for a while, it looked as though her exotic vehicles with director Josef Von Sternberg might overtake Garbo, but a fickle public tires quickly even of new things, and after the first few successes, that series was hemorrhaging. MGM was having trouble enough with their genuine article. Unless she could be softened, if not humanized, Garbo herself would run aground. The triumph that was Ninotchka proved she could play comedy, but the real magic was Ernst Lubitsch’s, though he was unable to get her on the phone for a proposed rematch. Bad move on Garbo’s part, for the next (and final) one left her to Metro’s ham-fisted mercies. Two-Faced Woman revealed what a truly bad vehicle can do to even the finest actress. Critics, whom she no doubt read despite assurances to the contrary, were aghast. They’d always considered her one of them, and above such vulgar exhibits. For all their feeling of betrayal, she might as well have co-starred with The Ritz Brothers. What was left of Garbo’s contract was settled with a willing Metro, but did she intend to quit for good?

Clarence Brown had been her most frequent director. He said Garbo intended to come back, but things happened and the chance got away. I suspect offers were tentative at best. Prestige she could bring to any table, but could Garbo assure ticket sales? That was surely an issue by the mid-forties. Her old films were considered museum pieces. The best of the talkies evoked literature class in high school. Old-timers spoke of her in reverent tones, and independent producers recognized Garbo as the ultimate "get" for projects in development. Walter Wanger persuaded her to test for one, but as is often the case, money was a bugaboo, and even the supposed magic of Garbo’s name was insufficient to raise it. She became a fast-moving target for rude photographers, hoisting the flag of scarves, floppy hats, menus, whatever was handy to shield that inscrutable face. Friends who blabbed were no longer friends. LIFE magazine celebrated her in the mid-fifties, and MGM exchanges took receipt of new prints in case showmen cared to re-run Garbo features. Art houses steeped in foreign product of uncertain stateside appeal could always depend on this one Hollywood star who’d long ago declared opposition to factory excesses. Greta was still the pin-up girl for disaffected intellectuals and the critics who flattered them. You’d watch her and imagine a font of wisdom, still water running to limitless depths . Quite the contrary, according to those with access. She seems not to have been anything other than ordinary, and niece/nephew relations in fact found her amiable and fun-loving during visits, so maybe all that wanting to be alone business was really just wanting to be left alone where strangers were concerned. Since those strangers included all of us, it was hard not to be a little resentful, but honestly, who’d enjoy being accosted in the street by people one’s never laid eyes on? In the end, a reasonable person would have to grant this woman as much privacy as anyone would be entitled to. Considering she’d been out of the entertainment business for so many years, Garbo had at least that coming to her.

Photo Captions

With Erich Von Stroheim in As You Desire Me

One-Sheet --- As You Desire Me

With Clark Gable in Susan Lenox

On The Set of Grand Hotel with John Barrymore

The Astor Theatre's SRO crowd for Queen Christina

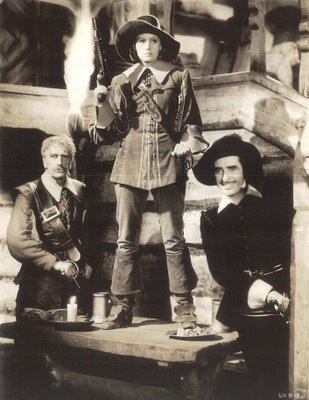

With C. Aubrey Smith and John Gilbert in Queen Christina

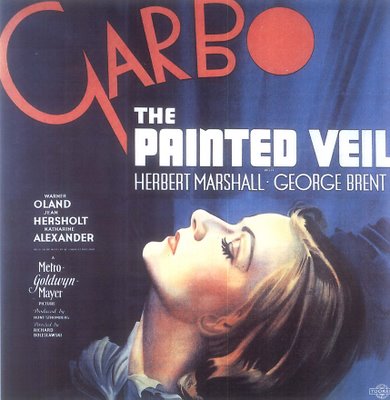

Six-Sheet art for The Painted Veil

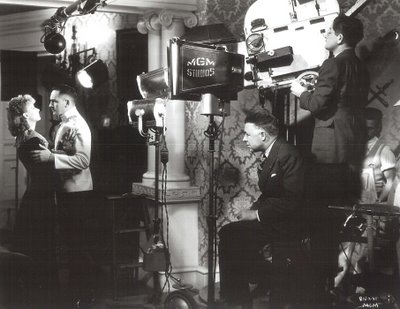

Clarence Brown directs Garbo and Fredric March in Anna Karenina

With Charles Boyer in Conquest

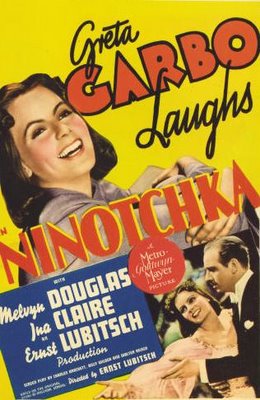

Ninotchka Window Card

Lampooned by Tex Avery and Co. in Warner's Hollywood Steps Out

Insert for Two-Faced Woman