Buried Treasures --- The Tall Target and The Young Philadelphians

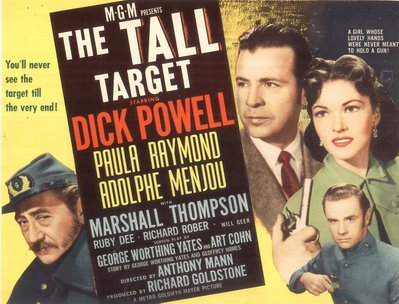

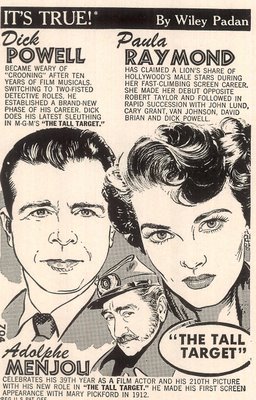

Buried Treasures --- The Tall Target and The Young PhiladelphiansA friend of mine who’s a Hollywood literary agent gave me a peek at a screenplay he’s getting ready to offer. The Lion’s Den deals with certain hidden aspects of the Lincoln assassination and the conspiracy behind it. I’d no idea that the Booth/Lincoln families intersected prior to that night at Ford’s Theatre, and came away from my reading with the hope that someday this script would find its way to the screen. The Lion’s Den also reminded me of another Lincoln-inspired thriller, The Tall Target, in that both utilized historic incidents as a launch for suspense and fast-paced action. In fact, The Tall Target, with its dramatization of a prior attempt on the President’s life, may be the only authentic pre-Civil War noir ever made. Certainly, it’s a unique and gripping depiction of a real-life chapter in Lincoln’s life I’d been unaware of. Anthony Mann directed this between Devil’s Doorway and Bend Of The River. He was quoted as saying that The Tall Target was his attempt to emulate Hitchcock, but these taut 78 minutes were more akin to Mann’s own T-Men, Raw Deal, and Railroaded, three budget noirs upon which his solid reputation was then based. They’d provide the critical and commercial traction to get him into Metro where crime thrillers and gritty westerns were perhaps more plentiful than a lot of us recall today. For a company primarily associated with musicals and glossy star vehicles, MGM veered toward meaner streets after the war. Major names were now doing on-screen police and detective work. Van Johnson, Robert Taylor, and Robert Montgomery were unexpected noir dwellers, but studio overhead demanded a steady flow of product, and the happy result was pictures like Border Incident, Side Street, Devil’s Doorway, and The Tall Target, all directed by Anthony Mann. The fact that three of the four lost money was no reflection on their quality. Border Incident, for instance, was a film without stars (and a final loss of $178,000), while Devil’s Doorway got by on Robert Taylor’s name and a modest $188,000 profit. Critics have mistakenly referred to Mann’s MGM output as "B" pictures. Economical yes, but these weren’t "B’s." Noirs at Metro subsisted on negative costs averaging around $750,000. The Tall Target had a higher tab of $966,000 and lost $594,000. Anthony Mann would need to move up to, and stay with, lucrative westerns with main line star James Stewart in order to become a money director.

Much of The Tall Target is viewed through the steam of its arresting locomotive. This was an ideal story for a studio with the best set and costume inventory in the business. A Metro historian more observant than myself could no doubt point out any number of plush chairs, gas lamps, and pocket derringers previously used in a hundred MGM releases dating back to silents. No one calls our attention to all that casual verisimilitude. It’s just there. Those seasoned artisans, many of them having been on the lot for decades, could summon up virtually any moment in history. What treasure troves those warehouses were, and what a tragedy they’d be so callously sold off within a few decades. Star making was a faltering enterprise by 1951. Metro had to know youngsters like Marshall Thompson and Paula Raymond would never make the feature grade, but it’s fascinating to note all the others that show up in largely uncredited roles. Barbara Billingsley? Even she had a run at Metro stardom (seven years of bit parts there between 1945 and 1952) before television conferred immortality. Star Dick Powell would at times seem to be paving the way for forthcoming Charles McGraw in RKO’s The Narrow Margin, its own arrival a matter of months away. There’s even an obnoxious kid riding both trains and supplying near-identical bumps in the narrative. Powell was by now on the cusp of TV entrepreneurship, and The Tall Target would be his final essay in the second career tough-guy persona he’d devised so brilliantly for himself. It’s interesting how a movie like this exists in a sort of obscure twilight, as if waiting for a DVD release to give it new life. You can see it on TCM if you’re willing to catch the train at its designated departure time, or perhaps set your Tivo.

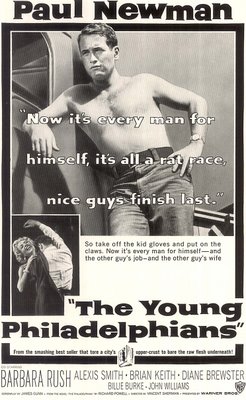

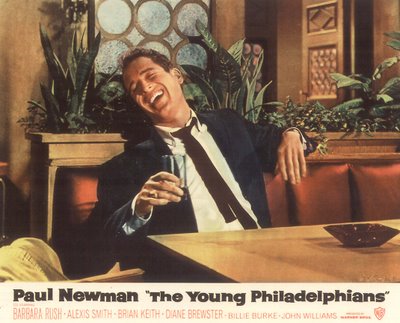

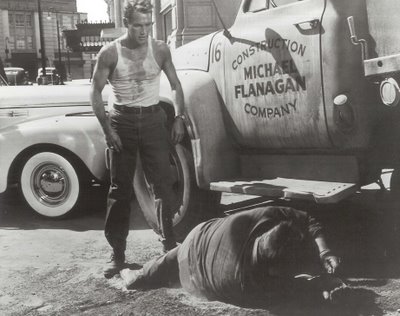

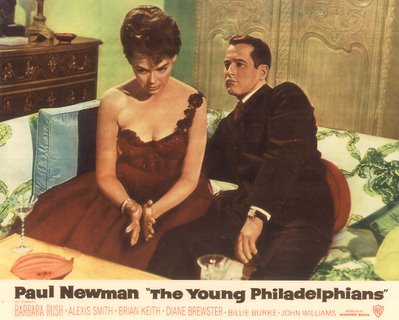

It’s quite a jump from all those resources at MGM’s disposal to the stripped-down economy of The Young Philadelphians, an otherwise tremendously enjoyable Warners melodrama just out on DVD. That title suggests a very specific background, but from the looks of things here, Warners might just as well have set it in Providence, Rhode Island, or Spartanburg, South Carolina. I hadn't the sense of even a second unit having gone to Philadelphia, let alone any of the principal cast venturing there. Warners spent $1.6 million on the negative. The picture doesn’t look cheap, but neither has it the care and production values that would have gone into something along the lines of Paramount’s Vertigo from the previous year, where the San Francisco setting was exploited to its full. Neither could it compete with your typical 20th Fox Cinemascope release, where backgrounds and art direction were vital elements of the whole. For all of that, I still prefer The Young Philadelphians over other selections in the Paul Newman DVD Collection. No other feature captures the Warner ethos quite so well, with its happy collision of up-and-coming stars (Paul Newman), eager beginners (Robert Vaughn, Adam West), and seasoned vets (Otto Kruger, Billie Burke, John Williams … that list is endless). Every time one of those balsa wood doors open, a welcome face emerges, and what inspired casting! Adam West as a Paul Bern-ish husband fleeing the marital bed, "Fred" Eisley just this side of Hawaiian Eye and vid greatness, Paul Picerni years before he’d become one of the most gracious of celebrities at autograph and collector shows. The Young Philadelphians is compulsive viewing. I’d challenge anyone not to like it, from inventive credits that reminded me of the later Ocean’s 11 to a climactic courtroom showdown pitting Newman against Richard Deacon. There’s something inherently pleasing about stories where nice guys are turned ruthless by experience and bitter circumstance. In this case, the worm turns early on and Paul Newman settles into what would become his dominant sixties persona. After prestigious turns in The Long, Hot Summer and Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, this had to have been regarded a comedown by the star. I suspect Paul thinks little more of The Young Philadelphians than he would of The Silver Chalice, yet he’s far more relaxed and natural here than amidst the lugubrious (and non-stop) confrontations of the Tennessee Williams adaptation. Playing opposite Paul Picerni would seem far less intimidating than scenery-chewing ordeals with Summer's Orson Welles, and Newman’s frankly more appealing with some of his intensity ramped down. Standing on tiptoes doesn’t necessarily enhance a star’s performance. The Young Philadelphians gives its supporting cast opportunity to rise to the occasion of meaty parts and show what they could do outside customary TV environs. Robert Vaughn was even nominated for an Academy Award here, having vaulted from Teenage Caveman rigors of only a year before. Barbara Rush and Brian Keith deserved higher profiles in features, though I wonder if the long-run money in prolific television work wasn’t actually better. Vincent Sherman brought tempo and variety to all such overheated mellers he directed --- I was reminded of his Ice Palace, The Hard Way, and The Damned Don’t Cry --- pictures like these can be mighty satisfying when executed by such a sure hand. There are many classics of a higher pedigree than The Young Philadelphians, but few you could spring on a general audience with as much assurance of positive feedback. By all means, try this one with your next movie gathering. Chances are they’ll thank you for it.

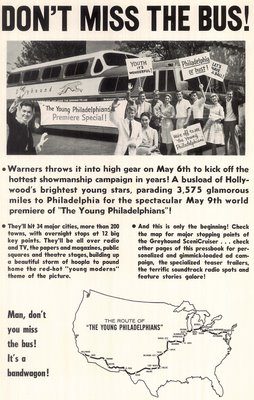

The Tall Target addressed a traumatic historical incident otherwise forgotten. So did The Young Philadelphians, only this one took place on a grueling cross-country publicity junket dubbed The Warner Transcontinental Star Parade by studio publicists. The idea was to load ten young contract players aboard a Greyhound "Scenicruiser" and transport them 3,475 miles from Burbank to Philadelphia, with stops in 27 cities and 200 towns. The bus would depart on May 6 and arrive at the premiere on May 19. At each stop, the players are instructed to pitch in wherever possible in granting interviews, posing for pictures, making theatre appearances, and, in general, creating good public relations for Hollywood as well as "The Young Philadelphians." The ten participants included Connie Stevens, Diane Jergens, Roger Smith, Alan Hale, Jr., Will Hutchins, Peter Brown, Jacqueline Beer, Troy Donahue, Ty Hardin, and Arlene Howell. Pounding home the red-hot young moderns theme of the picture from all those public squares and theatre stages had to be punishing work after sitting for hours aboard what I suspect was a sweltering bus (did Greyhound offer air-conditioning in 1959?) and traversing highways far less developed than those we enjoy today. Recalling my own family’s cross-country road trip to California in 1962, there were moments when it seemed we were pioneers in a covered wagon, such were travelling conditions in states like Arkansas and Oklahoma. For the modest wages these WB contractees were pulling down, this must have been akin to pulling oars in a ship’s galley. I’d love to hear from one of the survivors as to what they experienced.