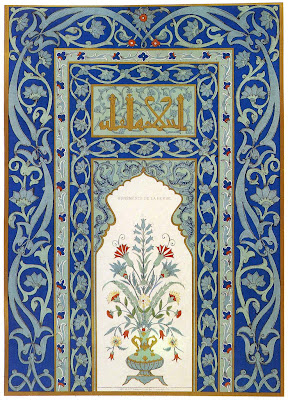

Illustration: Manuscript page, from Les Ornements de la Perse by Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont, 1882.

In 1882, Les Ornements de la Perse was published in France. It was produced by Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont and was part of a general European trend to both document and understand the major and minor decorative cultural styles of the world. Islamic pattern work came in for much attention due to a number of factors including the increasingly aggressive European influence on the Turkish Empire and its provinces leading to a point where France become de facto ruler of much of North Africa. Further east the expansion of Russian influence in Central Asia and the British in India brought both Empires face to face in Iran. Each Empire aggressively forced increasingly unrealistic and unfair concessions from Iran, which had to acquiesce in order not to be divided up between Britain and Russia, as had so many other nations throughout the region.

Illustration: Manuscript page, from Les Ornements de la Perse by Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont, 1882.

These and other factors gave increasingly liberal access to European explorers, designers, architects and collectors some of whom admittedly were interested in the novel and exotic. However, others were genuinely interested in the factors that went to make up design, decoration and ornamentation in what had previously been areas of the world with limited or no easy access to Europeans.

With so many publications being produced during the nineteenth century on Islamic decoration, sometimes more emphasis is placed on the authors and their European country of origin than the subject matter that they published. It is always hard to strike the right balance but it seems perhaps because of the beauty of the plates and their subject matter, it would be preferable in this case to concentrate on the illustrations from Les Ornements de la Perse.

Illustration: Borders from manuscript pages, from Les Ornements de la Perse by Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont, 1882.

Of the five examples shown in this article three are illustrations of Persian manuscripts, one of a carpet border design and one more showing a decorative panel of a door. These beautiful plates give at least some indication of both the range and technical skills that were available throughout the Islamic history of Iran. All are well balanced, harmonious and have a particular penchant for the use of floral motifs and pattern work that has made the Iranian decorative arts leaders not only in the Islamic world, but in the world in general. Designers and decorators across Europe used Iranian decorative styling across a number of disciplines, but particularly in ceramics, textiles, wallpapers and even book and metalwork design.

Islamic design, architecture and pattern work have been inextricably entwined with European architecture and decorative arts for so long that it is sometimes difficult to extricate and examine the obvious. Two simple examples are the Gothic pointed arch which is widely thought to have first originated with Islamic architecture, although there is still reluctance in certain quarters of Europe to admit to such, another being the more obvious arabesque which has been used constantly throughout European decorative arts history. There are a number of other examples some of which are long-standing while others are more recent developments.

Illustration: Border of carpet given by a Shah of Persia to Louis XIV of France, from Les Ornements de la Perse by Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont, 1882.

Owen Jones and William Morris were particularly interested in Islamic pattern styling for their different approaches to pattern and for that reason they were interested in different geographical areas or historical eras of Islam for their inspiration. Jones was interested in developing the idea of pure geometry as a working contemporary base for pattern work. Therefore, he was much more interested in the purer abstract styling of Islamic non-representational work. However, Morris with his lifelong interest in the dimension that the natural world could instil in contemporary pattern work was far more interested in Islamic decoration as interpreted through Iran. Looking at the illustrations shown in this article it is not surprising that Morris found affinity with the complex floral pattern work that is so much a part of Iranian styling. Morris himself tended towards the North Indian interpretation of Iranian decorative arts, but this was not so much a preference as a practical development as Morris spent long hours at the South Kensington Museum which had an increasingly large and developed collection of Islamic decoration from British India.

It is unknown whether Jones or Morris had a copy of Les Ornements de la Perse, although Morris did have a copy of Jones The Grammar of Ornament. However, what is certain is that publications like this one were important factors in extending the vocabulary of decoration and ornament. It must also have made it increasingly clear to those who critically leafed through books such as Les Ornaments de la Perse that decoration and pattern is a complex subject with many overlapping and borrowed innovations and general styling, an increasing number of which were to be designated as originating outside of the European sphere.

Illustration: Reposse work from a door of the College of Shah Sultan Hussein in Isfahan, from Les Ornements de la Perse by Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont, 1882.

It is perhaps wise for us to see the contribution that the decorative arts of Iran had not only on the general region that today's Iran occupies, but on a much wider scale which would include both the Islamic and European cultural regions. These illustrations can only give a glimpse as to the importance that Iran played in the development of pattern, decoration and ornament. That it has indeed been a vital factor in the journey towards today's contemporary pattern work, should go without saying.

I have used the term Iran throughout this article rather than Persia, even though the 1882 book title gives the name Perse. I hope this does not lead to any confusion.

Reference links:

Islamic Decoration and Ornament as seen by Owen Jones

Persian Ceramic Designs (International Design Library)

Persian carpet designs to color (The International design library)

Persian Designs (Design Source Book)

Persian Designs and Motifs for Artists and Craftsmen (Dover Pictorial Archive Series)

Persian Textile Designs (The International Design Library)

Indian and Persian Textile Designs CD-ROM and Book (Dover Full-Color Electronic Design)

Persian Textiles and Their Technique From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Centuries Including a System for General Textile Classification

Western Persian Textiles 18th-20th Centuries

Persian Needlework (Soozandoozi haie sonati Iran)

Persian Calligraphic Designs

Persian Ceramics: From the Collections of the Asian Art Museum

Persian Ceramics: 9th - 14th Century

Persian Rugs and Carpets: The Fabric of Life