Would The Circus Ever Come Back To Town?

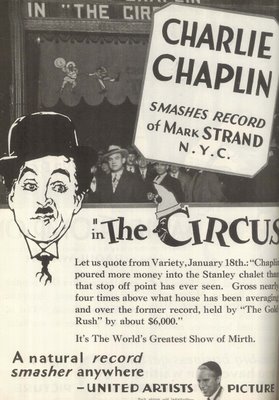

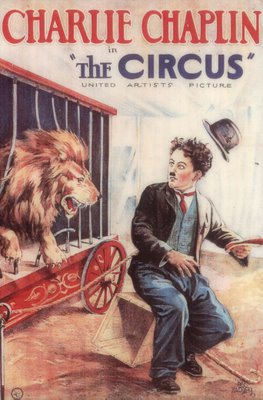

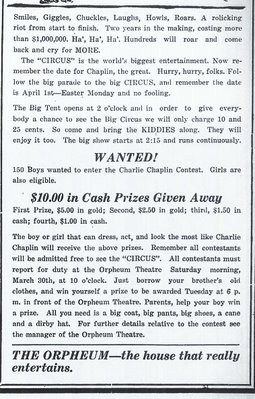

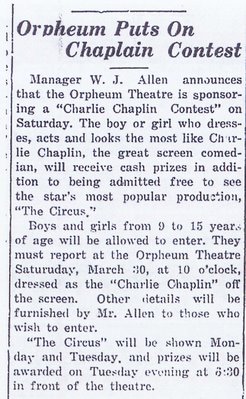

I’d have to assume there weren’t a lot of gold coins in circulation around my hometime back in April 1929, so the fact they were given away as prizes in a Charlie Chaplin Look-A-Like contest at the Orpheum Theatre is all the more astonishing in hindsight. Hard times for our community arrived long before the depression. I’ll bet people ate grass. Life was not unlike what we saw in To Kill A Mockingbird, except few houses were as nice as the one Atticus Finch occupied. The Circus had opened in January 1928 at the Mark Strand in New York. We got it fifteen months later. The Orpheum’s newspaper ad was the largest one submitted in all of that year (so much so I’ve broken it into two parts for illustration here), surpassing even their announcement of sound on disc in December 1929. Manager W.J. Allen would eventually take over the Orpheum (in 1941) and give it his name, operating the same clear through to a fire that would gut the premises in 1962. Boy and girl contestants from nine to fifteen were invited to don Tramp outfits and report to the theatre on Saturday morning, March 30. I’m betting a lot of them merely wore their school clothes for all the likely difference between those and Charlie’s raggedy screen attire. Parents would no doubt have lent assist toward scoring five dollars in gold (first prize), with another $5.00 for runners-up. Craven grown-up imposters might well don Chaplinesque garb themselves to get in on money like this, despite the stated age limit. I did ask one of our venerable locals (now in his nineties) if by chance he recalled the contest, but no luck.

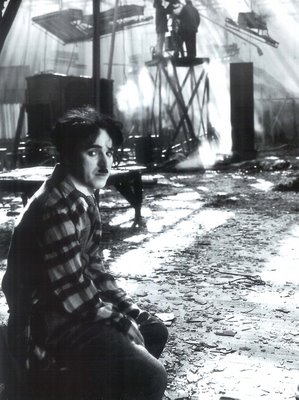

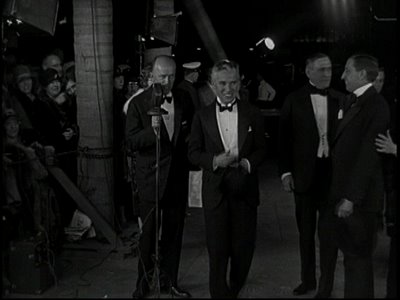

That Orpheum ad refers to The Circus costing over $1,000,000, and indeed, that isn’t puffery, for the final tab rose to $1.1 million, thanks to cost overruns brought on by a series of disasters that plagued production from start to finish. Chaplin's big-top tent blew away in a gale, then all the sets burned down in a cataclysm that nearly laid waste to the studio itself. This shot of Charlie amidst the rubble was a photo-op he could have done without, but I like the way he’s incorporated even that disaster into another visual chapter of individual myth-making. The nervous breakdown that followed put him on the ropes for another eight months of delayed production, and Lita Grey’s bird-dog legal team had designs on the unfinished negative (as with The Kid and Mildred Harris, Chaplin was obliged to hide it). The Jazz Singer had meantime opened in the Autumn of 1927, and holdovers for that one (as shown below) actually delayed The Circus openings in some houses. Latter-day legend abounds as to a critical and commercial chill, but Charlie’s new show was boffo, if not quite in The Gold Rush’s league (here he is at the Hollywood premiere). $1.9 million in domestic rentals led to a worldwide $3.008 total (against $2.2 domestic and $4.3 worldwide for The Gold Rush). For all that success, there were still a few exhibitor sourpusses, though it’s hard to imagine B.R. Parsons of the State Theatre in Springfield, Minnesota was watching the same movie as the rest of us when he wrote, If this is Chaplin’s best, I would hate to take a look at his worst. This is absolutely a lemon, the poorest thing I have seen in many a month. If you buy it for thirty-five dollars and sell it to the public for thirty-five cents, it might please. But don’t play it as a big special because it isn’t there. With support like this in exhibition, is it any wonder Charlie’s hair turned white by the end of shooting?

Circus sightings were rare in years to come. Chaplin had seen fit to bury it, owing no doubt to bad associations he’d maintained. Since C.C. owned the negative, United Artists could not exhibit the film without his consent. There were re-issues of The Gold Rush in 1942 and City Lights in 1950. Both did well. In the wake of Charlie’s re-entry troubles after the completion of Limelight, his films went into US moratorium. Collectors and Chaplin students walked black market by-ways in an effort to fill gaps on comedies they hadn't seen. William K. Everson maintained The Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society throughout the fifties, which was a private screening club made up of NYC film buffs. Bill prided himself on presenting titles otherwise inaccessible. The Circus was forbidden fruit of a particularly exotic flavor. Everson played it to the group, first in 1953, again in 1957, an excerpt in 1959, and finally complete again in 1964. His program notes from each of these shows are fascinating. The initial print was described as very much scratched and chopped up --- defects consist primarily of the clipping short of certain scenes, and the total elimination of certain shots --- it was, in fact, missing nearly a reel of footage. The one he presented in 1957 was taken from the same bootlegged negative, but was at least in better physical condition. In those days, it was a thrill seeing anything on The Circus. Revival theatres couldn’t get bookings, as Chaplin had no interest in making it available. Everson’s group, with their indifferent (and constantly changing) venues, straight-backed chairs, and chattering 16mm projectors was the only way you could view The Circus in New York for all those decades before Chaplin's authorized reissue finally came in 1969.

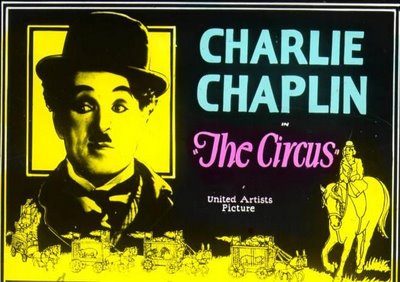

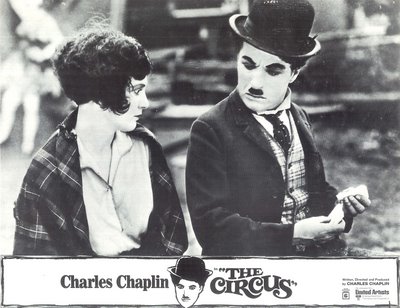

United Artists opened The Circus at the 72nd Street Playhouse on December 15, 1969. It was the first time a major distributor had gambled on a silent movie in years. Other Chaplins had played US dates in the late fifties. The Gold Rush and Modern Times were briefly available under the auspices of Lopert Pictures, a UA sub, but these had limited playdates. The Gold Rush got by on 338 engagements and brought back $89,000 in domestic rentals during 1959, hardly an indication that the public was ready to embrace Chaplin again. The Circus re-issue wound up going in the tank with just $97,000 in domestic rentals (though foreign reached $921,000). Prints and advertising would have eaten up most of that, as UA did prepare new posters and trailers for the revival. The finish line was flat rentals at kiddie matinees. After 808 playdates, The Circus was unceremoniously dumped (compare that number with other UA releases of the period --- Battle Of Britain had 9,885 dates and The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes, another flop, 3,307). A pity so few (stateside) people saw a movie for which Chaplin supplied an all new musical score, and pristine 35mm prints to showcase it. United Artists' loss was the private collector’s gain, however, for within months, 8 and 16mm pirated negatives were surfacing in underground labs across the country, and The Circus was available for (albeit unauthorized) purchase. Mine was in 8mm, and the cost was $40. The dealer from whom I acquired this hot potato lived in a trailer just beyond the fence of a well-known insane asylum down in the eastern part of the state. He even provided a reel-to-reel tape of Chaplin’s new score to go with the feature. That was in 1971. By 1974, I’d graduated to a 16mm bootleg from a seller whose address was somewhere in the California desert (perhaps near that sweltering location where Stroheim shot Greed? --- you'd like to think so). This time I paid $140. Playing it for a fifty cent admission at my college that year, I half expected Chaplin himself to swoop off Swiss alps with his team of lawyers. Those prints are long gone now, and The Circus is readily available, like so many once inaccessible titles, on DVD. I sometimes wonder if our pleasure in films like this might have been enhanced by the sheer difficulty of seeing them. Watching The Circus again this week was enjoyable enough for me, but I can’t say the experience approached the excitement of unspooling that renegade 8mm print back in 1971, and trying to synchronize the sometimes recalcitrant tape that accompanied it!

Special Thanks to Dr. Karl Thiede for invaluable data and assistance with this article.