Of Dallas and Comfort Westerns

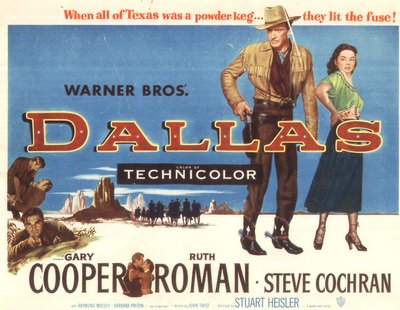

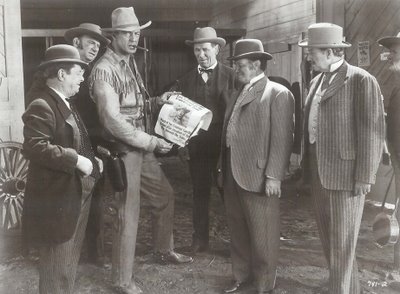

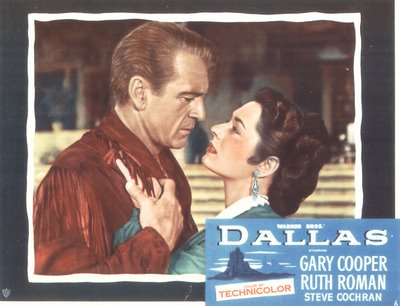

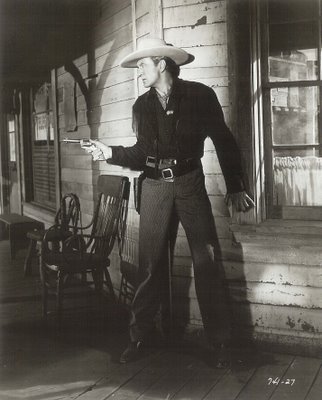

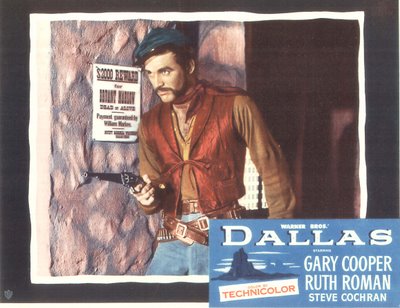

Of Dallas and Comfort WesternsIt must have come as quite a shock when Gary Cooper received the script for his fourth starring vehicle under the Warner's contract he'd signed in 1948. After three classy features (The Fountainhead, Task Force, and Bright Leaf) with first-rate directors (King Vidor, Delmer Daves, and Michael Curtiz), Dallas was a distinct comedown. It had been announced for Errol Flynn, but Cooper was assigned at the eleventh hour. The studio's choice of journeyman Stuart Heisler to direct was hardly a vote of confidence. If you look at Cooper's gag cameo in the previous year's It's A Great Feeling, you get a pretty good idea of how his new employers regarded the star. The appearance is brief --- Cooper is carelessy photographed (at a time when age was starting to betray him), and the exchange with Dennis Morgan trades on old yup and nope routines that had dogged him since the beginning of his career. Two decades of fine performances had taken Cooper way beyond that insulting cliche, yet here he was, engaging in self-parody that had to rankle. To some extent, Dallas is more of the same. There is Technicolor, though it doesn't flatter him (in 16mm, his hair looked almost orange at times, even on original dye-transfer prints), and the whole thing has a slapdash, backlot feel about it. So my recommendation? You must get this movie! It's practically a textbook on the declining careers of a pre-war generation of great leading men, that fallow period during the late forties when youngsters like Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster, and Robert Mitchum were getting the really interesting parts, while veteran stars---Gable, Flynn, Cooper --- were having to get by in studio product with no allowance made for changing times, or the leading man's advancing age(s). Gary Cooper is fabulous in Dallas, giving his best to a bad job. He's winging dialogue, peppering dull scenes with quirky mannerisms; in short, making plenty out of nothing --- getting a lemon, and giving us lemonade. Watch for his introductory scene --- it's a classic --- and only Cooper could make it look so good; burning that wanted poster and lighting his cigar --- great. The leading lady is Ruth Roman --- I guess that's where Warners saved some money. After all, Coop didn't come cheap. For the record, Dallas had a negative cost of 1.390 million (significantly below the money spent on his previous WB's), and final worldwide rentals were 4.490 million, so Cooper in a western was still boxoffice. Too bad WB didn't think enough of him to put a little more effort into the piece. I still love it though, and what a kick to see Raymond Massey in a seedy land-grabber villain role (and Steve Cochran's his brother!). Bet Massey loved telling that one to his lunch companions at the Player's Club. Barbara Payton's there too. Read her sleazy auto-bio, watch this movie, and think about it. There's lots to like in Dallas --- a wonderful Max Steiner score --- Cooper masquerading as a "dude" --- and a sock finish when he finally corners Massey. High Noon was a year away, but you could argue this one’s more fun….

Cooper no doubt wondered when a Broken Arrow or The Gunfighter might arrive to rescue his western prospects, but for stars too high-priced, if not overly typed , these bolder projects seemed denied. Warners found it simpler, and more lucrative, to continue on autopilot with increasingly formula vehicles along the lines of Dallas (1.9 million profit), Distant Drums (2.2, one of WB’s biggest that year), and Springfield Rifle (1.3). What’s the sense of challenging the Cooper audience with thoughtful scripts when these were pulling such figures? Dallas is really little more than a variation on the Randolph Scott model, and those were being turned out two to three a year by directors no more inspired than Stuart Heisler. It works, as little care seems to have been applied, so unlike pretentious westerns of the Broken Arrow school, it’s loopier and more unpredictable. Dialogue comes out of left field. You don’t get a sense of anyone looking over writer’s shoulders. What’s at stake when you know the fans will be there in any case? Cooper’s less inhibited and more willing to fall back on old tricks. Dallas gives full vent to his way with breaking up lines, flexing trigger-fingers, and doing that showdown walk reserved for westerns he couldn’t otherwise take seriously. Confusion over whether Dallas was serious or send-up merely enhances the fun, for Cooper seems to have come in some days willing enough to play straight, while on others he’s back in Along Came Jones mode, less self-consciously this time and all the better for it. You can’t help feeling sorry for Raymond Massey, though. There’s one agonizing scene where they put him on horseback --- a real horse --- and the man looks terrified. Only two years previous, he’s wearing three-piece suits behind the owner’s desk at The New York Banner, and now this (but worse was yet to come, for within a few months, he’d be tangling with Randolph Scott in Sugarfoot!).

High Noon (an outside picture) might have turned the tide at anyone else’s home studio, but Warners saw no reason to elevate Cooper toward more challenging work --- thus there was Blowing Wild, which had him hauling nitro and shunning Barbara Stanwyck. Opening sequences are near identical to Treasure Of the Sierra Madre, as though some of that quality might rub off. I’m only sorry Warners no longer owns this negative, for it would make a great addition to The Gary Cooper Collection --- Volume Two. Dallas is happily available however, and don’t let anyone kid you it’s among the lesser offerings. Any western that pairs Steve Cochran and Barbara Payton as desperado lovebirds has to be getting something right, even if unknowingly. I understand the two frequently repaired to remote corners of the backlot for R&R. This I would expect from Cochran/Payton, but where was Coop? Surely he exercised a leading man’s prior claim, and my understanding of B.P. suggests she’d have been more than willing, as even model of rectitude Gregory Peck succumbed to her charms when they made Only The Valiant a year later. There’s a major biography of Barbara Payton forthcoming, and the author’s website includes a sample chapter. Based on that, it should be definitive. In the end, I’d imagine Dallas to be the sort of commonplace western Dean Martin used to watch on his television instead of going out with Frank and the boys. No academic will write monographs about this one. It’s the ideal respite from intellectual and emotional demands made by The Searchers and The Wild Bunch, as one’s own advancing age makes these seem somehow more oppressive. I used to wonder why middle-aged men sitting in front of the tube made no distinction between a John Ford and an Audie Murphy. Now at least it seems a little clearer. I’d never have interrogated my father with regards the aesthetic gulf between Red River and an episode of Wagon Train. Dallas and Audie and the lesser Scotts entertain without imposing, and that’s well enough for those men who prefer enjoying their westerns without being turned inside out.