Mae West --- Part Two

Mae West --- Part TwoNearing forty before stepping in front of cameras, Mae West was a frequently overweight and by now anything but alluring figure who, nevertheless, brilliantly portrayed a sex symbol. It was through exercise of indomitable will that she presented herself as America’s foremost man-eater. Love scenes were always about build-up, never consummation. When time came for the kiss, her leading man would spin Mae away from the camera so we’d seldom see lips meet. Male co-stars could always depend on at least one close-up of the back of heads. Sexual excess always took place off screen, even in the pre-codes. For movies all about Topic A, hers are the most sexless of all. Men lavished Mae with diamonds and furs, but there was seldom even suggestive dissolve to indicate what their remuneration might be. Any given actress at Warners scored more illicit fadeouts (if not on-screen couplings) in a month than West would in an entire career, but none got so many laughs out of it, and that’s what finally tripped Mae up with the censors.

Mae didn’t just wink at sex in interviews --- she gorged herself on it. A policy of provoking media critics had worked to her advantage in New York, but these were far more provincial movie audiences she was tweaking, and their patience wore thin with ribald tales of West’s legion of lovers. Viewers were laughing with her, but she was laughing at them. It was time to bring Mae down a few pegs. Forceful demonstrations by the Catholic Church got the fearful message across --- either clean up or close down. West had three pictures in release when the newly enforced Code paid a call. Paramount exchanges were obliged to pull these for shelf duty, while her newest, It Ain’t No Sin, went back to drawing boards. In view of scrutiny applied here, there'd surely be no sinning by the time it reached theatres. The title was first to be jettisoned --- some were offended by it --- thus Paramount yanked down billboards and issued recall to a nationwide flock of parrots that had been trained to recite, It Ain’t No Sin! for benefit of passerbys. Leo McCarey directed, salvaged a good picture out of wreckage, then vowed in accordance with colleagues before and after never to work with her again. Mae confounded the PCA edict by shooting highly censorable footage, then meekly submitting to its removal, knowing stuff she really wanted wouldd be overlooked during furious exchange of memos. That worked for a while, but you can only fool some of the people part of the time, and these weren’t fools she was up against. Indeed, they would have her movie career on a plate within a few short years.

Mae didn’t just wink at sex in interviews --- she gorged herself on it. A policy of provoking media critics had worked to her advantage in New York, but these were far more provincial movie audiences she was tweaking, and their patience wore thin with ribald tales of West’s legion of lovers. Viewers were laughing with her, but she was laughing at them. It was time to bring Mae down a few pegs. Forceful demonstrations by the Catholic Church got the fearful message across --- either clean up or close down. West had three pictures in release when the newly enforced Code paid a call. Paramount exchanges were obliged to pull these for shelf duty, while her newest, It Ain’t No Sin, went back to drawing boards. In view of scrutiny applied here, there'd surely be no sinning by the time it reached theatres. The title was first to be jettisoned --- some were offended by it --- thus Paramount yanked down billboards and issued recall to a nationwide flock of parrots that had been trained to recite, It Ain’t No Sin! for benefit of passerbys. Leo McCarey directed, salvaged a good picture out of wreckage, then vowed in accordance with colleagues before and after never to work with her again. Mae confounded the PCA edict by shooting highly censorable footage, then meekly submitting to its removal, knowing stuff she really wanted wouldd be overlooked during furious exchange of memos. That worked for a while, but you can only fool some of the people part of the time, and these weren’t fools she was up against. Indeed, they would have her movie career on a plate within a few short years.

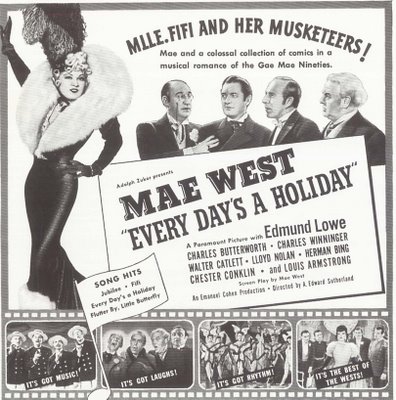

Throughout nearly fifty years living in Hollywood, Mae’s phone number was listed in the book. Not that she was accessible. Fans weren't wanted up close. Once she’d been robbed at gunpoint. The lowlife element figured West for a walking jewelry counter. Well, she was Diamond Lil after all. Violent crime sometimes walked hand-in-hand with celebrity. Mae’s chauffeur/lover and bodyguard both carried guns, while their employer cradled a pet monkey within the linings of her fur. Similar eccentricities were visited upon business associates as well. Mae knew how to keep opponents off balance with extravagant demands and seemingly irrational behavior. By the time they got back their equilibrium, the deal was done, and she had won. It all worked like a charm until the grosses started drying up. Mae West was suddenly like every other actress who'd scorched 'em in pre-codes --- de-clawed and deadly dull. Klondike Annie varied the formula by having her impersonate a missionary, and this she played without irony or condescension. It might have been the best and bravest screen work she ever did, but it was too late. The finishing touch came unexpectedly when Mae guested on The Chase and Sanborn Hour with Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy --- this night that would live in radio infamy was December 27, 1937. Her own proposed script had been nixed by network standards, and she team-played through rehearsals, but when that live broadcast light went on, Mae threw caution to the wind and plunged forward with double-entendre laced dialogue that had much of the country running for telephones telling friends to tune in. NBC was apoplectic, and vowed never to allow Mae West on radio again. Resulting bad publicity sent chills through Paramount soundstages. Motion Picture Herald listed her among stars now labeled "Boxoffice Poison." Efforts to surround West with aged low comedians in Every Day’s A Holiday couldn’t rehabilitate her. The combination of circumstances made getting rid of West a sound fiscal decision for the studio.

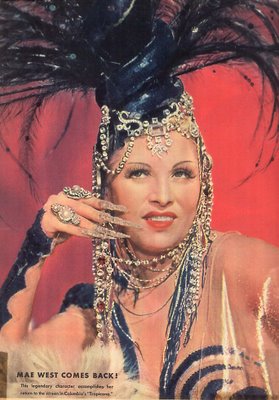

She found refuge back on the stage. A decade long obsession had been to film her play, Catherine Was Great. Now she would weigh herself down in period costumes (one topped the scales at 75 pounds) and take it on a torturous road schedule that wound a path through the provinces and brought the thrill of Mae West In Person to hundreds of smaller towns she’d not encountered since vaudeville. Hollywood still gave her the freeze --- a teaming with Bill Fields did him more good than her, and The Heat’s On for Columbia was a plain disaster. Canteen work during the war was out --- Mae was no good with small talk and loathed the close contact these spots entailed. She was insulted when Billy Wilder offered Sunset Boulevard, but imagine how scary Mae would have been as Norma Desmond --- poor Joe Gillis could never have survived the opening reel of her not-so tender ministrations. Muscle boys in her Vegas cabaret act found Mae a hard taskmaster as well. One of them was sufficiently traumatized by her insatiable demands (both on and off stage) so as to quit the show and join a monastery. Those platform shoes Mae wore made Karloff’s Frankenstein boots seem like carpet slippers by comparison --- straps cut into feet and left her in agony. Mae's own hair and eyelashes were long since ruined with chemicals and enhancements over the years. Now she was a mannequin that had to be dressed as though for a window display. Sister Beverly was an off and again servant who drank. Resentments festering for years boiled up from time to time. When Mae decided to tackle her memoirs, she found that rats had eaten old documents and records. The play was still the thing. Mae West now spoke of herself of in the third person --- there was little of the first person left. Interviewers began commenting on the eerie and gothic nature of encounters with her, and this would become the rallying point for lazy scribes. She was the only cast member in Myra Breckinridge not utterly degraded for participation therein (poor John Huston!), staying above that fray with tried and true material instead of submission to gauchery of a desperate to be with-it Fox. One last starring vehicle at age 84 (Sextette) was clearly not in her best interests, but Mae never knew when to quit, and you had to admire her gamely seeing it through. Performing was the life she knew, age a thing to be daily conquered and overcome. That last hospital stay found her hauling a 16mm projector into the room so she could screen movies --- Mae West movies, of course. She died in 1980 at the age of 87.

Photo Captions

Ad Art for Klondike Annie

Klondike Annie

Paramount Publicity Portrait

Ad Art for Every Day's A Holiday

Every Day's A Holiday

Publicity Still with Charlie McCarthy for The Chase and Sanborn Hour

With W.C. Fields in My Little Chickadee

Color Portrait for Tropicana --- released as The Heat's On

Newspaper Ad for Mae's Stage Show

With musclemen for her Las Vegas Cabaret Revue

With the cast and director of Myra Breckinridge