The Elusive Charley Chase

The Elusive Charley ChaseCharley Chase was never an easy comedian to track down. Television exposure of his short subjects was virtually non-existent from the beginning. They were syndicated in the early fifties, but I’ve never spoken to anyone who saw any of them. We certainly never had them down here when I was growing up. About the only way you could see Charley was in one of those Robert Youngson comedy compilations, or on 8mm home movies from Blackhawk Films. Youngson devoted a third of his Four Clowns in 1970 to Chase, but by then it was really too little and too late. To this day, Charley Chase languishes in a no-man’s-land of stored and forgotten negatives --- his talkie output and a number of silents are presently hoarded by the Hallmark Card company, and they’ve got about as much interest in Charley Chase as I have in Britney Spears (did I spell that right?). The only ones you can lay your hands on are public domain shorts originally released by Pathe in the mid-twenties, and Kino Video has done nicely by these in two volumes they've so far released on DVD. To be sure, Chase’s output is a mixed bag. Some of the comedies are gems, some are pretty appalling. Like a lot of other technicians in those days, Charley had deadlines to meet. Sometimes the work met standards, and sometimes it didn’t. Maybe he wasn’t Chaplin, Lloyd, or Keaton (damn those unfair comparisons again!), but Chase deserves a lot better than the obscurity he’s got, and even though I fear he’ll never get the recognition he has coming, there’s still a lot to like for those of us willing to claim membership among a particularly rarified viewing niche.

Like a lot of up-from-nothing performers in those days, Charlie Chase played hometown street corners before small-time vaudeville took him out on the road. Ever notice how easy it was for people to leave home and strike out on their own in those days (well, I'm sure it wasn't easy)? Not like now where guys in their thirties still live in their parent’s basement. Anyway, Charley ends up with Al Christie, then Mack Sennett, and finally Hal Roach. He works with Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd at the very beginnings of their careers. You can see him in some of those frenzied Chaplin Keystones where he’s a dapper young man always getting splattered with something gooey and repulsive. It must have been depressing for these young guys to have nice suits ruined like that. When I watch Charley take a pie, or go head-first off a pier, I always wonder if his wardrobe was provided to him, or if that’s his personal attire getting drenched. Hard for me to picture Mack Sennett picking up a dry-cleaning bill for a struggling beginner. Chase finally gets to wear dry clothes when he goes to Roach as a director. Walrus-mustachioed types like Snub Pollard get the benefit of Charley’s seasoned way with gags. Chase would say later that a good man with comedy was the one with a good memory, for even the clammiest routines could be re-cycled every seven years as new generations entered the viewing marketplace. Is it coincidence then that Disney would later re-issue its animated classics on approximately the same schedule? Chase clearly observed that rule throughout his career, as much of his talkie stuff was reworked from the silents. But for the departure of Harold Lloyd from Roach, Charley might have stayed behind the camera, but they needed a Lloyd type to cover the loss, so he got a starring series beginning in 1923.

It always seemed to me that Charley got a bit of a screwing at Roach. Every time he’d hit a stride with talented writers and/or directors, Roach would "promote" them up to another series he was pushing, and Chase would be left to start all over again with green beginners he’d have to train and develop. Not that he wasn’t up to it. Leo McCarey credited Chase with teaching him everything he learned in the business, but even McCarey got yanked away from the Chase unit when Roach recognized his extraordinary supervisory and directing abilities. Charley was essentially providing traction for a lot of talent that would go on to have bigger careers than he ever would, and that’s kind of sad when you consider that it happened over and over. Meanwhile, his own comedies were building a solid audience, and when he peaked around the 1926-27 season, Charley Chase was the biggest comedy name at Roach, but that would not last long. Laurel and Hardy were just then getting together, and their astounding success would forever eclipse Chase at his home studio. Personal issues, including a major drinking problem, made it that much worse. His voice was ideally suited to the new talkies, but Charlie still got the short end where supporting talent was concerned. No sooner had he established a felicitous teaming with Thelma Todd than Roach withdrew her for a starring series with ZaZu Pitts, and by the by, that $1,750 per week Charlie was getting at Roach was not nearly what he was worth. Even Charley’s own brother, James Parrott, was pulled off his team to go work with Laurel and Hardy. Pretty demoralizing, particularly when it was all Chase could do to show up for work in the morning, his health being what it was.

It always seemed to me that Charley got a bit of a screwing at Roach. Every time he’d hit a stride with talented writers and/or directors, Roach would "promote" them up to another series he was pushing, and Chase would be left to start all over again with green beginners he’d have to train and develop. Not that he wasn’t up to it. Leo McCarey credited Chase with teaching him everything he learned in the business, but even McCarey got yanked away from the Chase unit when Roach recognized his extraordinary supervisory and directing abilities. Charley was essentially providing traction for a lot of talent that would go on to have bigger careers than he ever would, and that’s kind of sad when you consider that it happened over and over. Meanwhile, his own comedies were building a solid audience, and when he peaked around the 1926-27 season, Charley Chase was the biggest comedy name at Roach, but that would not last long. Laurel and Hardy were just then getting together, and their astounding success would forever eclipse Chase at his home studio. Personal issues, including a major drinking problem, made it that much worse. His voice was ideally suited to the new talkies, but Charlie still got the short end where supporting talent was concerned. No sooner had he established a felicitous teaming with Thelma Todd than Roach withdrew her for a starring series with ZaZu Pitts, and by the by, that $1,750 per week Charlie was getting at Roach was not nearly what he was worth. Even Charley’s own brother, James Parrott, was pulled off his team to go work with Laurel and Hardy. Pretty demoralizing, particularly when it was all Chase could do to show up for work in the morning, his health being what it was.

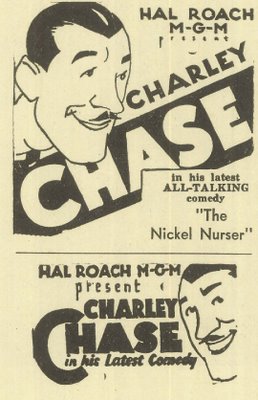

These trade ads from 1926 represent Charley’s season in the sun with Roach. Within a year, Laurel and Hardy would break out and dominate publicity materials from that point on. His Wooden Wedding is one of the notable Chase silents --- there’s comedy here they’d never dare in today’s restrictive marketplace. It’s available on one of the Kino DVD’s. These rare newspaper ad mats were typical of the stock materials provided to exhibitors playing a Chase short. All they had to do was insert the appropriate title. In this case, it’s The Nickel Nurser. That’s Tommy "Butch" Bond with ice-cream man Charley in I’ll Take Vanilla, and off-screen squeeze Muriel Evans in Young Ironsides. His weakness for blondes had Charley in hot water at home, and that hand-carved Meerschaum pipe he kept filled with marijuana was the source of much studio gossip. The wild life has clearly caught up in these later shots. The graying temples on view here in Neighborhood House (his last short for Roach) was nothing new in 1936, but Hal had made him black his hair almost from the beginning, and Charley was only now letting it go natural. The new look couldn’t help but emphasize the age (yet he was only 43!). The little girl on stage with Chase is Our Gang’s Darla Hood. With double features crowding out short subjects, Roach let Charley go soon after this. The Columbia comedies that would wind up his career were a generally inferior lot, but as with Buster Keaton at the same company (and at the same time), there were moments to treasure. Chase did a lot of writing and directing here, and some of the best Three Stooges shorts from this period are his. A final shot from 1938 (with Ann Doran) was nobody’s idea of flattering, but it does offer a game comedian still giving it his all despite worsening health concerns that would allow him only two more years beyond the date of this pose (he died in 1940).