1952 Hollywood Eats It's Own

The Bad and The Beautiful was MGM’s black-and-white melodrama counterpart to the joyous musical celebration of old Hollywood that is Singin’ In The Rain. And it is indeed "old" Hollywood that both these films seek to commemorate, as they were made by technicians who had themselves given decades of service to the studio establishment. Everyone’s favorite movieland myth seems to have made its way into The Bad and The Beautiful. Historically speaking, that porridge doesn’t always jell, but why leave anything out? No one was checking dates and events that closely in 1952. "Hollywood History" seemed like an oxymoron. Why research a subject that was so ephemeral to begin with? Would Metro have dug into back issues of Photoplay to insure accuracy? I doubt it. Seems more likely that a handful of old-time industry vets, probably sitting around a card table (much as they do in the party scene during the movie) or walking down the fairway at Lakeside Country Club, came up with most of the anecdotes that resulted in the three dramatic episodes of The Bad and The Beautiful. The movie actually has a casual, scrapbook quality that makes for great repeat viewing. It’s very much like Singin’ In The Rain in that respect. The tortured adherence to historical verisimilitude that would come years later with things like The Aviator is thankfully missing here. It’s the spirit of Hollywood they wanted to capture, and at that, The Bad and The Beautiful succeeds brilliantly.

I wonder how the town’s aging charter membership felt whenever they saw one of the silent era’s discarded relics getting a sympathy (if that) cameo in these fifties movies. It was not an uncommon thing. Ford and DeMille used to decorate their sets with fallen idols, and Metro kept a roster of once celebrated day players, now reduced to crowd scenes and walk-ons. It wasn’t just old actors in the waste bin. John Ford took joy in pointing out one-time big shot director King Baggot, now an extra, to upstart beginner Robert Wagner when they were doing What Price Glory --- this happened the same year The Bad and The Beautiful was made. That minister with an affected, booming testimonial for Kirk Douglas’ father in the opening reel of T.B.A.T.B. is Francis X. Bushman, well-known hard luck case who’d even run print ads seeking a wife (any wife!) to save him from poverty. Bushman was typical of the cast-off generation --- good for occasional press (which he, and Metro, got for having appeared here), but strictly hands-off when it came to substantive work. His feature finish would be in 1966 with The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini (notice how the title itself implies end-of-career degradation?). Deserted mansion motifs come into play several times in The Bad and The Beautiful. One serves as baleful home of deceased, and debt-ridden "Hugo Shields", father of the Kirk Douglas character, referred to as "not a heel … he was the heel." That was inspired by Lewis J. Selznick, and son David threatened to sue when he got wind of it (never did, of course). The Shields/Selznick parallels were pretty cheeky in view of the fact that DOS was still an active producer at the time --- could it be the town already knew he was slipping and decided to have a little fun at his expense? The other crumbling ediface belongs to a dead Hollywood martyr modeled after John Barrymore. Kirk Douglas and Barry Sullivan are able to walk right through the front door. I found myself wondering if deserted Hollywood residences were really so accessible after their owners went broke or passed on. Were these old homes so unattended at that time? If I’d been around in 1952, could I have toured Barrymore’s former digs, or Valentino’s legendary Falcon’s Lair without a pass, as it were? Somehow that scene in The Bad and The Beautiful does have a ring of truth about it, as if it were based on repeated, actual incident.

Vincente Minnelli’s essential snobbery comes through in those scenes wherein he depicts the filming of a western and a horror movie, two genres he clearly knew nothing about, and cared less. The staged cowboy stunt looks patently phony, even when we know it’s supposed to look phony. It’s as though Minnelli were saying, "See? This is the way all westerns look." Very condescending, Vince. His biggest sneer is reserved for horror movies, presented here as the bottom-scraping start of Kirk’s career as a movie producer. It’s a Cat People-inspired "B" that Val Lewton-esque Douglas lifts out of the doldrums by suggesting scare scenes instead of showing the monsters. Minnelli and his writer’s general disdain for horror themes is amusingly portrayed by a costume shop scene where tatty cat suits are modeled by run-down-at-heels prop assistants --- truly a low-rent district of the industry Minnelli wants no part of. The "Gaucho" character played by Gilbert Roland is a real anachronism. This had to have been noticed even in 1952. He’s presented as a "Great Latin Lover", which is fair enough if we’re dealing with the silent era, but Gaucho’s bestriding the top rungs of stardom in what is implied to be thirties/forties Hollywood, a time when Latin types were relegated to B’s and supporting roles (with Gilbert Roland chief among them). The only serious push for a latter-day Valentino seems to have been Paramount’s disastrous wartime efforts on behalf of one Arturo De Cordova, a real stiff that blighted a handful of expensive productions (Frenchman’s Creek, A Medal For Benny) before fading into obscurity (though he did go back home to Mexico where he enjoyed greater success). The "Von Ellstein" character, based on guess who, is presented as an autocratic untouchable all Hollywood is dying to work with … at a time when his real-life inspiration, Erich Von Stroheim, literally went begging for jobs (a group of sympathetic Metro employees actually got together a food and gift basket for the Stroheim family one Christmas during the mid-thirties, so dire were his circumstances at the time). Leo G. Carroll’s Hitchcockian director is priggish and vain. You wonder what Hitchcock said to Carroll after he got a squint at that portrayal. Chances are he laughed along with everyone else. It’s really Selznick that comes in for the drubbing, as more or less played by Kirk Douglas here. His later movies are presented as grotesque overproduced monstrosities. It’s like watching Selznick behind the scenes on Duel In The Sun, The Paradine Case, and Portrait Of Jennie. Very insulting to DOS. I don’t blame him for being annoyed.

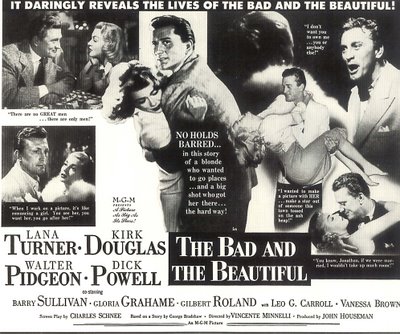

Maybe 1952 audiences didn’t get all the references in The Bad and The Beautiful, but they did go to see it. In a year when most of MGM’s product lost money, this one brought back a $534,000 profit against a negative cost of $1.5 million, with domestic rentals of $2.3, foreign at $1.0, for a worldwide total of $3.4 million. As you can see from these ads, it was sold for glamour, sex, and melodrama. The fashion tie-ins were a natural for a period movie that never went to undue pains in evoking a period, so all the clothing and sets looked more or less contemporary. You may not want to score yourself on that Bad and The Beautiful "friendship and romance" quiz, as it’s pretty much spelled out that if you total below 40, you’ll come to a bad end. The very interesting on-the-set candid shows Minnelli directing (on the boom) as Leo G. Carroll "directs" on the stage below, as though two films were in production at once. Boredom inherent in sitting around waiting on a sound stage is captured by this shot of Carroll and Walter Pidgeon listlessly playing checkers as a barely interested Kirk Douglas looks on. A dreary business, this moviemaking. That’s Vincente Minnelli touching up Lana Turner’s non-existent eyebrow (she’d shaved them off for a thirties role and they never grew back). This had to be for publicity, as I imagine the union would have frowned upon Vince invading their fiefdom. Once again, the Germans give us a powerful image for a movie poster --- Kirk looks almost maniacal here.