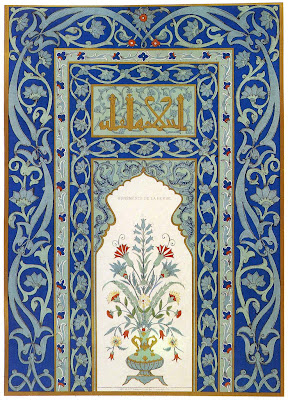

Illustration: Persian manuscript page.

The influence of Islamic decoration on the decorative arts of Europe has been both fundamental and long-standing. From the early medieval period onwards the influence on European surface pattern in particular, has been an important element both as an inspiration and as a developmental tool. The interaction between southern Europe and North Africa for example, proved to be creatively inspiring, producing an inter-locking cultural mix of Islamic, Classical and Christian motifs and pattern work that was to produce some of the most important developments in textile pattern work.

By the nineteenth century one of the main areas of intrigue and fascination for Europeans involved in the decorative arts was that of Persia, modern day Iran. The history of the decorative arts in Islamic Persia was considered by many Europeans to be of fundamental importance, with highly sophisticated decorative work that could do nothing but be inspirational to designers in Europe. The extension of the Persian culture into Northern India through the Moghul Empire had proved to be particularly inspirational to the British who came into direct contact with the cultural heritage through their assimilation of India. It was this combination of Persian and Northern Indian decorative work that proved to be so inspirational to a number of British designers.

Illustration: Indo-Persian manuscript border designs.

Decorative pattern work in Islam came in many forms and tended to be spread across most of the decorative art disciplines. It was therefore used on an inspirational level within European industries that supplied the growing interiors market. Ceramics and textiles proved to be particular beneficiaries in the latter half of the nineteenth century with both disciplines producing a formidable amount of work, both obvious and subtle, with Britain being particularly susceptible to the style.

Islamic decoration tends to be perceived as following two main themes geometric and floral, and while this is true to a certain extent, there is a complexity to the culture, one that has incorporated a number of different regional and cultural themes, that makes this too simplistic, but sometimes useful when dealing with the larger themes of pattern work. Interestingly, of the two perceived themes, the British in the nineteenth century tended more towards the floral than the geometrical, despite the persistent persuasion of such critics as Owen Jones who saw the fundamental and varied building blocks of the geometrical as a perfect vocabulary for an endless complexity of pattern.

Illustration: Persian manuscript page.

All of the illustrations shown in this article are facsimiles of historical Persian manuscripts that were reproduced for a European audience to both marvel at and see as being potentially inspirational. In some respects, they were produced as an historical and cultural evaluation of Persia, but they were also an obvious portfolio of possible decorative techniques for use in contemporary European pattern work. The percentage of active inspiration depended on both the individual designer and the company involved. William Morris for example, was both intrigued and inspired by Persian and Moghul decorative qualities and techniques, but did not actively copy any of the results that he came across in his research. However, his surface pattern work in both printed textiles and carpet design did use some of the general techniques that could be found in Persian floral decoration. It is sometimes not always the direct approach to observational inspiration that is the most useful; often it is the slow and almost sub-conscious result that proves to be the most rewarding. However, others were more aware of the direct allure of what was termed as the 'Orient' and its potential for profits, and therefore a much closer observational inspiration was chosen.

Whichever path proved to be the most profitable, the creative or material, or even a combination of both, Persian and Moghul elements seeped into the decorative format of nineteenth century British decoration. So much so that the imported style can be seen as being an intrinsic part of many of the formats and disciplines that made up the decorative arts, from textiles to ceramics, and from illustration to metalwork. Some of the decorative inspiration is practically and blatantly obvious as in the output of Liberty for example, while some is much less so and forms a foundational level, as in the case of Morris and Co.

Illustration: Persian manuscript page.

However, no matter what the level of inspiration, it is fascinating to evaluate the influences and cultural overlaps that are always such a part of the history of decoration. It is intriguing to see the historical possibilities that may have been produced between the creativity of two different cultures in different parts of the world. The creative connections formed by Britain from that of Iran, many of which were not necessarily consciously achieved, show how important this form of cultural fermentation has been in the development of the decorative arts in general and in that of Britain specifically, an island that has always had a natural tendency to absorb decorative formats, embellish even transform them and then redirect them for both domestic and external markets. It is this form of creativity that perhaps lies at the heart of Britain's nineteenth century relationship with both Iran and its Moghul extension in British India.

Further reading links: