Illustration: Decorative ceiling of the Carved Parlour, Crewe Hall, England.

Crewe Hall is a Jacobean mansion located in Cheshire, England. It was originally built between 1615 and 1636, although restored, renovated and expanded over the generations. The hall is fortunately still standing, so many have been dismantled over the twentieth century, and although altered it is still considered one of the finest Jacobean houses in England. The three examples shown here are illustrations of the decorative ceilings at Crewe Hall, some of which are the original decoration produced for the house in the seventeenth century.

Decorative ceilings have always been popular from the earliest cultures right through until the end of the nineteenth century and in some cases into the twentieth. However, despite many of the examples that are readily available from so many different periods, it was not a decorative format that was limited to the wealthy. Although stucco ceilings specifically might well have been out of the financial reach of many that did not stop ceilings of the more financially restrained showing the love of decoration and pattern. Many of the smaller cottages of England for example show evidence of painted beams, rafters and ceilings, very often seen in carved wood or using a stencilled technique, giving lively and colourful pattern work that followed the medieval fascination with floral tendrils, birds and even fantastical animals, much of it produced on an amateur scale and on an amateur budget.

Illustration: Decorative ceiling at Crewe Hall, England.

The ceilings of Crewe Hall are a fascinating glimpse of how far decorative art could be expanded in order to encompass all levels and surfaces of an interior. Although they may well not fit in with our own limited and constrained decorative palette, they do show much of what was considered normal for the vast length of the history of decoration, such as a high level of showmanship, a projection of perceived wealth, as well as an understanding of sophistication and belonging. Much of the history of the decorative arts has been about wealth and the showing of that wealth. However, there was also a whole level of the decorative arts that often seemed almost invisible compared to the projections the aristocracy and semi-aristocracy. These two groups of individuals although dominating society seemed often to have had the most fragile egos and were dominated themselves by a sometimes acute sense of insecurity.

As stated earlier, even the relatively financially poor or socially unconnected decorated their homes as best they could, and although this may well have served the same purpose as the wealthier individuals, a projection of status, wealth and sophistication, it also must surely have had at least an element of joy in the use of internal decoration for its own sake. That these forms of decorative art were often not commented on or critiqued, says perhaps much about the stratified snobbery of both decorative art in general and the critic specifically.

Illustration: Decorative ceiling at Crewe Hall, England.

In some respects, by concentrating our admiration on the decorative elements to be found only amongst the rich, we degrade and marginalise the decorative formats adopted, expanded and reimagined by the poorer elements of society, who, through much of human history including our own, were often the majority of the society and therefore the norm.

The nineteenth century Arts and Crafts movement in England tended to concentrate not only on the ideal of the craftsmanship of the ordinary artisan, but also of the decorative work that those artisans supplied, much of it being distributed through the working and lower middle classes, rather than the aristocracy. It is easy to see why the English Arts and Crafts movement quickly took on a political rather than purely decorative stance, with Socialism being at the heart of the movement with its celebration of the working man and woman and their contribution to the creative culture of England through generations of innovation and tradition.

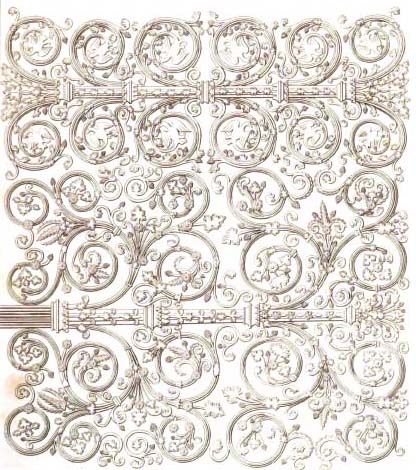

Illustration: Carved wood ornament.

The irony of course was the fact that many in the English Arts and Crafts movement who celebrated the achievements of the ordinary working artisan were selling work produced in the same vein to the rich and powerful of England not to the ordinary citizens, an irony not lost on those intimately involved in the movement and an issue that still dogs the English craft world today.

Therefore, although the ceilings as well as interiors in general that were produced for the wealthy are extrordinarily beautiful and should be treasured as some of the finest workmanship produced during their respective decorative ages, the decorative details that can also be found in the more humble homes across England should also be celebrated as equally beautiful and treasured. After all, fine workmanship is fine workmanship and all adds to the celebration as a whole of English decoration, not just that supplied to the aristocracy.

For anyone interested, there is a good Wikipedia site for Crewe Halland can be found here.

For anyone interested, there is a good Wikipedia site for Crewe Halland can be found here.

Further reading links: