Region 2 Round-Up --- Part One

Region 2 Round-Up --- Part OneRegion 2 can be a rich vein in which to mine for DVD rarities. Sometitles available across the pond may never see light of day here. It’s true our hardware won’t play them, but there’s (easy) ways around that, and effort of retrofitting your player (or purchasing a so-called region free model) is rewarded ten-fold by features like A Distant Trumpet, and 1962’s The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse , along with many others which continue to surface in countries like France, Germany, and the UK. Legendes Of Cinema and Collection Grands Classiques Du Cinema Americain are French umbrellas for DVD groups dedicated to auteur directors. We might wait years to get some of these released stateside. I’ve enjoyed eight this past week, and have found quality consistent with what’s released here. The PAL conversion resulting in a slight speed-up is something I’ve not noticed, but I can’t hear dog whistles either, so maybe there’s advantage after all in growing old and deaf. My first submersion was Fritz Lang’s Moonfleet, released in 1955 and largely ignored since. Maltin’s guide calls this one tepid, but I didn’t find it so. A welcome antidote to kid-friendly pirate movies, especially those which share a child protagonist, Moonfleet is refreshingly adult and way more sophisticated than earlier Disney and MGM forays into similar waters (Treasure Island being most similar). Lang didn’t have luxury of prep time he’d enjoyed in Germany, but Metro expertise in staging period pageantry is still intact, though for perhaps a last time with Moonfleet (did they do another serious in-house costume picture after this?). It’s absence from the MGM Children’s Matinee inventory during the late sixties/early seventies reflects an integrity and refusal to soften material for juvenile sensibilities (though 1955 kids surely enjoyed, and were probably flattered by, Moonfleet’s mature approach). Atmosphere is well maintained throughout. Graveyard scenes are creepy and onscreen deaths are at times grisly. George Sanders’ presence reassures that we aren’t watching a kiddie show, despite moments when his disinterest was such that I thought GS might actually nod off on camera. I see where Moonfleet lost nearly a million dollars, no disgrace as other worthy Metro pictures of that year performed even worse (The Cobweb and It’s Always Fair Weather, for instance). The Stewart Granger actioners were losing ground just as Robert Taylor’s costumers hit the rocks. Both Moonfleet and The Adventures Of Quentin Durward ($908,000 lost) put paid to future MGM ventures along these lines. Were audiences as content to sit home watching Sir Francis Drake and Richard Greene’s Robin Hood on their televisions?

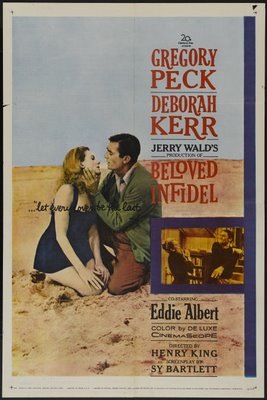

Gregory Peck plays some excruciating drunk scenes in 20th Fox’s Beloved Infidel, a supposedly fact-based story of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald’s affair with Hollywood columnist Sheilah Graham. The movie was produced by post-Peyton Place Jerry Wald, so you’d expect more of a cutting edge, but director Henry King (who applauded the Code and its strict application) lends an old-style formality that no doubt contributed to a $1.5 million bath his studio took on this picture. Hollywood decadence is suggested by extras chasing each other around a sound stage pool, and never was Tijuana depicted so clumsily as here (WB’s Viva Buddy cartoon from 1934 seems near-documentary in comparison). Eddie Albert is again the alcoholic’s best friend and severest critic (must it always be Eddie in such parts?). Greg crawls in and out of his bottle like a serial hero in quest of the treasure map, while Deborah Kerr forgives and waits patiently for a next walloping. Beloved Infidel is what they once called "mature entertainment", but for my money, The Colossus Of New York offers more nourishing food for thought. Best parts were shot around the Fox lot and on sound stages, lending Beloved Infidel what little verisimilitude it has. Though specific studios aren’t identified, at least we don’t resort to signs above gates reading Mammoth, Monarch, or Miracle Pictures, as so many filmland depictions invariably do. They’re shooting In Old Chicago during one sequence, but the haughty and pampered leading lady gets a (fictional) name other than Alice Faye. It’s doubtful any but the most sharp-eyed observers in 1959 would have noticed origin of that scene being filmed, since In Old Chicago had been out of theatrical circulation for years, and was otherwise a fixture (among hundreds of other Fox oldies) on late night television. Latter-day viewers will be alarmed to see Gregory Peck drinking from a smuggled quart bottle of gin on a passenger flight (and no seat belt either!), while Deborah Kerr occupies what appears to be the plane's lone sleeping berth (at least it’s an upper!). The only thing lacking is one of those observation platforms such as Bill Fields enjoyed in Never Give A Sucker An Even Break. Welcome character support Herbert Rudley graduates from The Black Sleep to play Peck’s producer boss. The two were old friends from starting-out days and Greg threw Herb work both here and in 1958’s The Bravados. Movies about drunks are frustrating for predictable seesaw characters invariably ride. The only question is whether he/she will live or die in a final reel, but this being Fitzgerald’s story, even that element of suspense is vitiated by our knowledge he’ll surely collapse before that finish.

Curse Of The Fly was, for me, the most unnerving of that waning series. I didn’t even bother going to see it in 1965, but should have. The poster implies more (literal) flies in experimental ointments, but thankfully, there’s none of that. Credibility might well have been strained to breaking points had yet another housefly gotten into the teleportation (is that what it was?) chamber just before switches were turned. Besides, that last Fly head was so oversized as to be unwieldy, Fox no doubt operating on theories that the bigger the appendage, the scarier its effect. In fact, the opposite was true. Curse Of The Fly’s mid-sixties arrival must have surprised fans. You wouldn’t have thought they’d do another one of these after a six-year lapse. This time out, actions have real consequence for the accursed Delambres, as failed experiments over an indeterminate period have left any number of mutated unfortunates imprisoned among convenient cells within the family compound. Fleeting glimpses of these provide harrowing moments in the show, and notions that former wives are stored up along with the rest lends queasy reality that’s a real departure from lazy and conventional shocks delivered by previous Return Of The Fly. Characters emerge from aforementioned chamber with nasty radiation burns (as if portly and drink-addled Brian Donlevy needed yet another handicap!), while mutants, leads, and whatnot are transported willy-nilly from one continent to another without so much as a by-your-leave. I was actually confused as to who went where by the end, though I suspect a few luckless individuals were left in a kind of phantom zone transit similar to the one that entrapped General Zod and his compatriots in the Superman features. Donlevy contributes one of those I’m giving it my best even if it’s unworthy of me performances that were hallmarks of so many leading men reduced to low-budget sci-fi pics in the fifties. A pity he couldn’t live long enough to realize what a devoted following his Quatermass and similar experiments would have among middle-agers who grew up with them. Curse Of the Fly was made for a remarkably frugal $108,000. How could you help but get a profit having spent so little as that? --- and yet there was only $145,000 in domestic rentals and $115,000 foreign. After prints and advertising, the picture ended up dead even, one of the few titles on Fox ledgers that fell neither way.

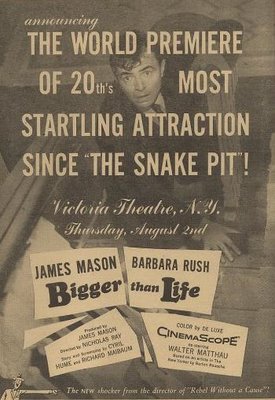

Monsters From The Id seem to have been turned loose in a number of family men during those alleged "repressed" fifties. Walter Pidgeon in Forbidden Planet is an extreme example, but James Mason gets Bigger Than Life by a mere overdose of Cortisone, which I assume they don’t hand out so freely (at least in pill form) anymore, judging by his psychotic reaction here. Initial euphoria leads Mason to imagine there’s an escape from middle-class obligation and petty compromises, and tragedy comes in the realization there’s no way out. Academics have performed tribal dances around this show for decades (or at least since auteurism gained currency), as it seems to confirm all their assumptions about a bleak post-war social landscape. Bigger Than Life is bound to have depressed a lot of 1956 drive-inners unprepared for such an unsparing dissection of their workaday traps. Word-of-mouth was surely ruinous. The fact it would lose $875,000 for Fox might have been something they saw coming from first previews. I wonder if 20th even realized prestige for having made it. Unlike phony-baloney preachments of their late-forties social ventures, Bigger Than Life went right to the bone, and kept slicing. You could dismiss it as melodrama, but only if you’re not paying close attention. Kids ignorant of adult ramifications would have been horrified by one of their number suffering relentless parental abuse. I was so bothered upon seeing it on NBC’s Monday Night At The Movies in 1963 as to avoid further contact for what ... forty-four years? Just this week, I finally steeled myself to watch Bigger Than Life again. Never was the desperation of family responsibility so chillingly enacted. Show this to your teenagers if you want them to stay single. Recent shows like American Beauty and Election undoubtedly drew inspiration from director Nicholas Ray. It’s a miracle Bigger Than Life even got made. Producer-star James Mason must have called in a lot of markers. Why not put Robert Wagner on a horse and have at least some chance of getting your investment back? In fact, that’s exactly what Fox and Nicholas Ray would do the following year with The True Story Of Jesse James.