AIP Loses Its Innocence

Few of us would propose Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine as one of the seminal films of the sixties, but from the standpoint of American-International Pictures and exhibition in general, it does represent a turning point. Within months after Goldfoot’s release (November 1965), AIP would abandon virtually all of its old formulas and embrace what we now remember as The Sixties. Consider the cultural divide between The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini (released April 1966) and The Wild Angels (July of the same year). A weakened Production Code was being dismantled in favor of an eventual ratings system. Nicholson and Arkoff saw all of this coming and overhauled their schedule to meet it. The rubble left behind included beach movies, strongman epics, Corman/Poe thrillers --- all those beloved staples we'd associated with AIP would be replaced with bikers, protesters, retro-gangsters spun off Bonnie and Clyde --- even the posters got ugly. I remember being shocked, but more depressed, at seeing The Wild Angels. There’d be no crossing the divide back to those AIP pictures I’d enjoyed but a year before. If it was possible for a boy of twelve to lament a lost youth and innocence, then I most surely did upon seeing this one. Goldfoot played against the setting sun of the fun sixties, when The Four Seasons, Beach Boys, and early Beatles provided background music for life that was more an extension of the fifties than an indication of darker things to come. No doubt there were hints of changes on the horizon, but I didn’t see them during that winter of 1966 when Goldfoot played the Liberty. Neither, I suspect, did showmen whose grass-roots ballyhoo as shown here would itself disappear from the exhibition scene.

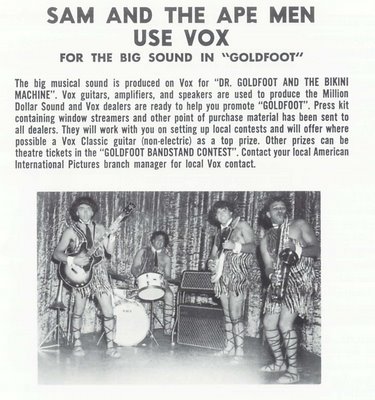

Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine had the sort of Wow opening in Milwaukee they don’t get anymore. Back then, every arm of media opened wide to enthusiastic campaigns like this one. The Palace Theatre had a teenage couple parading downtown streets clad in the film’s signature gold tuxedo with matching shoes. Dr. Goldfoot "money bags" were presented to various news editors when the youths dropped in on Milwaukee dailies. Chocolate coins (wrapped in gold foil, natch) and gold balloons soon adorned copy desks as reporters tied in with the Palace for advance Goldfoot promotion. The kids also hit local TV stations, where vid personalities featured them along with clips from the movie. Since this was a December opening for Milwaukee, Goldfoot figured into the annual Christmas parade by way of a yellow convertible (closest thing they had to gold, I suppose) festooned with signs promoting the show. Radio giveaways included watches, cameras, guitars, shoes, and nylons, all of these contests touting Goldfoot. There were four "teenage rock and roll bands" performing nightly in the Palace lobby (though hopefully not at the same time) and kids were encouraged to dance around the concession area. "The famous bikini machine float" (shown as backdrop for the band here) toured drive-ins, and Vox musical instruments allied with AIP to push both the film and their product. Dr. Goldfoot got national exposure when he was paged during three football games broadcast over CBS. The black-and-white kine captures shown here are from an ABC Shindig special which ran November 18, 1965. The Wild, Weird World Of Dr. Goldfoot featured a sort of pocket version of the movie (with musical interludes) in which Tommy Kirk and Aron Kincaid stood in for the feature’s Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman. There were surprisingly no scenes from the feature itself, though Vincent Price and Susan Hart did appear to reprise their roles. If you want an idea of how primitive network television could look as late as 1965, by all means check this out. It’s included as an extra on Vincent Price --- The Sinister Image, a DVD collection of interviews and V.P. ephemera.

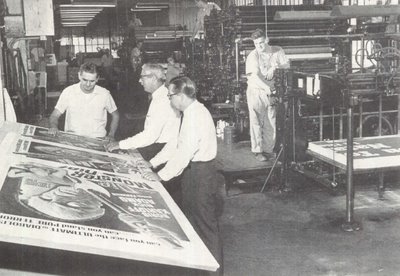

Sam and The Ape-Men is a band I Google-searched. Other than a single Goldfoot reference, nothing came up. They’re featured during a nightclub sequence in the movie, and yes, they wear animal skins. I’m not aware of AIP having released a soundtrack album for Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine, so there’s no certainty as to whether any of Sam’s work survives on vinyl or CD. The title song, however, was recorded by the Supremes. It’s listed as previously unreleased and available in a CD box set released in 2000. The feature itself is a sort of unholy wedding between spy spoofery and the horror genre, with Beach Party personnel stopping in for cameos. Much of Goldfoot’s behind-the-camera talent dated back to Griffith’s day. Director Norman Taurog was a veteran of both Larry Semon silents and Jerry Lewis rib-ticklers. There are actually sight gags with a Murphy bed here, possibly the last time such a prop would be used in a contempo-set comedy. Scriptwriter Elwood Ullman, having penned for Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and the Stooges, furnishes routines that interlock nicely with any number of two-reelers playing television at the time Dr. Goldfoot was released, while verbal references call up (distant) memories of the old Fitzpatrick-Traveltalk series that MGM had discontinued years before. The big San Francisco-based chase finish is an extravagance one wouldn’t expect from AIP, but coming just two years after It’s a Mad … World and in the midst of far more energetic pursuits being staged (routinely) at Disney, it comes off a distant second. Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman, both neatly attired in suit and tie, are as distinctly retro as the Blues Brothers would so self-consciously be in the late seventies. Ray gun sound effects are borrowed from MGM’s Forbidden Planet track, and Hickman’s strapped down on the still-standing Pit and Pendulum table, augmented by long-shot footage of John Kerr in a similar predicament from the 1961 thriller (I remember sitting in the theatre wishing I was watching that rather than Dr. Goldfoot). The rentals for Goldfoot ran pretty even with what the beach series had been getting. 1.1 million was the domestic take, a little less than How To Stuff A Wild Bikini (1.3), but ahead of the disappointing number that finished off that series (The Ghost In The Invisible Bikini with $745,000). American-International’s poster art was often as not the most memorable aspect of these shows. The photo here shows the quality control crew at National Screen’s Continental Litho plant in Cleveland, Ohio (poster collectors will surely recognize that name) checking out just printed sheets for Die, Monster, Die, an AIP release that opened a month before Dr. Goldfoot and The Bikini Machine.

American-International was given to grandiose announcements of future projects. Since the early sixties, they’d promised "roadshow" specials. Now it was May 1966 and AIP was entering into a grand scale phase, which would begin with three films in the three million-dollar class. Top name talents and top directors would lead off with Rocket To the Moon, a Jules Verne adaptation starring Bing Crosby as P.T. Barnum. It was only weeks before European location shooting began that Crosby dropped out and Burl Ives was substituted. The resulting picture, released finally as Those Fantastic Flying Fools, and at a cost of far less than three million, was a disaster for AIP ($282,000 in domestic rentals). There were large-scale musicals on tap --- one of them a major Broadway classic, according to press releases. A high-camp hillbilly comedy was budgeted at $1.25 million (itself more than AIP had thus far spent on any production), and there was even a remake of The Golem planned! All of this was scuttled when The Wild Angels broke out in July. This was a smash hit of the sort they’d never had before. $4.290 million in domestic rentals was more than twice the money AIP had realized on their biggest previous success, Beach Party. By the end of September, the company would announce an immediate slate of "protest" pictures dealing dramatically with realistic commentary on our society and times. James Nicholson (shown here with future wife and Goldfoot star Susan Hart) said these pictures would not be aimed at the youth market, but would instead fit into the category of general audience pictures similar to "The Wild Angels." Nicholson refused to disclose specific details in the interest of protecting the subject matter (!). In the meantime, they’d still be handling Thunder Alley, a follow-up to the very successful Fireball 500, and Dr. Goldfoot and The Girl Bombs, an import sequel that flopped. Within the year, beach parties were out and bikers were in. Little kids (including myself) that made up a large portion of the audience for shows like Dr. Goldfoot were now confronted with Born Losers and The Trip. AIP was happy enough to leave the youngsters behind, as the protest pics brought in far more teenage (and adult) dollars, enabling the company to finally mount some of those blockbusters they’d been planning, though the crash-and-burn of De Sade probably made them wish they hadn’t.