In Defense Of Satan Met A Lady

In Defense Of Satan Met A LadyWarners recently issued a three-disc special edition of The Maltese Falcon. In addition to a substantially upgraded 1941 version, there are two earlier adaptations of the story that WB produced during the thirties. Both have been unjustly ignored, if not maligned, for many years. Their ongoing status as unwanted stepchildren was reflected by the modest cost of renting both during United Artist’s non-theatrical 16mm heyday. These prices tell the story --- The Maltese Falcon of 1941 was available at $125 per day in 1976, $175 by 1981. The 1931 Maltese Falcon played (few) colleges and film societies at $35, again in 1976, then a measly $60 for 1981. Satan Met A Lady went from $75 to $85 over the same period. I would love to know how many bookings each of these had. 16mm rental would have been about the only way most of us could see those first two versions until TCM came along. I’ll never take for granted the ease of access we now have to both. The memory of those tantalizing stills in Bill Everson’s The Detective In Film and Citadel’s Films Of Bette Davis books, and my mid-seventies conviction that I’d never get to see these movies makes all the more astonishing the fact that, not only can I buy them now … I can buy them at Wal-Mart. For those of us who used to stay up till 3 AM for once-in-a-decade showings of a single classic title on television, DVD and satellite TV are a continuing miracle. That first Maltese Falcon was known as Dangerous Female so as to avoid confusion with the Bogart picture. A lot of writers thought it was actually released under that title in 1931. I was delighted to see the original credits restored on the new DVD. The movie itself is no slouch either, despite pacing a little slow in comparison with other, zippier, Warner pre-codes of the period. Line readings seem overly measured at times. The 78 minutes it takes for director Roy Del Ruth to get the story told could have been disposed of in 65 by a Michael Curtiz. Ricardo Cortez was steeped in playing outright heels, so it's no surprise seeing some of that bleeding into his Sam Spade, but any show that counts Dwight Frye, Thelma Todd, and Walter Long among names in support is by definition a must-see. There’s just no way that John Huston wouldn’t have watched this in preparation for his remake.

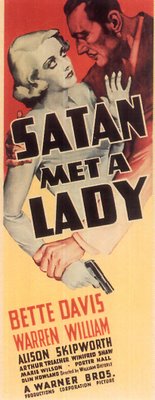

Coming five years later in 1936, Satan Met A Lady was like a cheerful, preemptive rebuke to everything that would be taken so seriously in 1941. It is the whoopee cushion beneath the rear of every critic who has reverently probed the greater meanings of Huston’s classic. They had to give dishes away wherever "Satan Met A Lady" was shown, said a Warner publicity man shortly after the film posted initial losses, and yes, it was a "flop" --- negative costs were $195,000, domestic rentals topped out at $266,000, with foreign only $48,000. Considering that loss of $60,000, and the previous deficit of $75,000 on the 1931 version, you’d almost wonder why they kept remaking this thing. Bette Davis was top-billed, having come off an Academy Award win for Dangerous the previous year, and she’s part of the reason Satan Met A Lady fared so miserably in public hindsight. If you couldn’t see it on television (and we surely couldn’t here in NC), why not take her word that it was one of the worst pictures ever made? Reviews of the time backed Davis up. There is no story, merely a ferrago of nonsense representing a series of practical studio compromises with an unworkable script, said The New York Times. Imagine my surprise last week when I watched it for the first time and discovered what a delightful screwball mystery it is. Those who would uphold the sanctity of Dashiell Hammett should prepare themselves before watching, for his novel is altogether upended by an irreverence gleefully mocking detective movie conventions that were themselves years away from being established. They call Warren William Ted Shane in this --- a name that fits, and one he carries lightly. Sam Spade would have been too intense and burdensome for Warren, whose boisterous cad of a screen persona ran loose for a glorious half dozen or so years before Code strangulation and the actor’s own health issues curbed his activities. Those increasingly flippant Perry Mason mysteries seem to have limbered Warren up for Satan Met A Lady. As far as he’s concerned, this is pure madcap comedy, and he's brilliant in it. If anything, Bette Davis’ discomfort arose from her inability to keep pace with her co-star’s energy. Warren William left Warners shortly after Satan Met A Lady. The pre-code garden where he’d flourished had been plowed over, and his time was past.

It was the obscurity of the first two Maltese Falcons that made a third one possible. The 1931 version would have undoubtedly been denied a Code seal had Warners submitted it for a re-issue in the late thirties, and Satan Met A Lady was adjudged a failure. The studio’s faith in the story was steadfast, however, and the 1941 remake went forward with a determination to finally keep faith with the Hammet novel. Toward that end, it succeeded, but Huston’s film also adopted a straight-faced approach that would have bemused Ricardo Cortez and Warren William. Stakes were never higher than in this Code-dominated world, and every action had real and immediate consequence. Light-hearted attitudes toward sex and crime were unthinkable. Sam Spade paid his dues. Were it not for the artistry of that cast, and Huston’s crisp direction, this would have been an investigation as labored as those conducted by John Hodiak in Somewhere In The Night, or Mark Stevens in The Dark Corner. There weren’t many laughs on the road to film noir. Detectives of a Warren William sort could not have survived here. The Maltese Falcon set the pace for many that would come, but pre-code and screwball elements were no longer welcome. No wonder the previous Falcon and Satan Met A Lady went into deep freeze. There was something almost irresponsible about them. Bogart’s Sam Spade carried the banner for all Code-compliant Hollywood detectives. The solid critical reputation of The Maltese Falcon effectively took it off the burner for purposes of further remakes. Had it not been so well received, I’ve no doubt we’d have seen it adapted again. Consider a possible fifties treatment. Frank Lovejoy as Sam Spade? How about Steve Cochran, or even Gene Nelson? Why not Dennis Morgan? Direction in the capable hands of Andre DeToth, perhaps, or Stuart Heisler. For all I know, the Falcon was remade on any number of 77 Sunset Strip episodes, or Hawaiian Eye. The property was too good to simply ignore. I’ll bet Stu Bailey cracked variations of this case on multiple occasions, with Tracy Steele bringing up the rear the following season with his own Falcon-derived investigation. Warners was shameless about recycling their old properties on those fifties detective shows. Why would The Maltese Falcon be any more sacred than the rest?