Alfred Hitchcock Blog-A-Thon Today!

Better writers than myself have been flogging the Hitchcock oeuvre for the past forty years, and in deference to them, I’ll spare you my own ruminations on the deeper meanings of the Master Of Suspense and his films. The Film Vituperatem is the host for today’s Blog-A-Thon devoted to Hitchcock, and you can go HERE for coverage and events related to this auspicious celebration. There’s nobody I’d rather talk about than Hitchcock, having done it previously HERE and HERE, but finding fresh game to lay upon that table is something else again, for this is far and away the most discussed and (over) analyzed director in the history of movies. Well, why not? His work is so accessible. You don’t watch him out of a sense of duty. His shows are a pleasure even for teen-agers otherwise hostile to classic film. In all the college programs I’ve done, Hitchcock always rings the bell. You don’t have to justify Hitch or apologize for him. There’s never a need to put this director in historic context or make excuses for dated devises. There's no begging your audience to just give him a chance. Girlfriend Ann saw Psycho theatrically at the Liberty in 1972. We bonded on her memory of that day (but why wasn’t I there --- being an hour away at college was no excuse --- I should have walked home for that!). I did get to spend a day watching him direct Family Plot (then called Deceit) on a Universal sound stage, and stood there the whole time thinking what an epochal moment this was in my life. Hitch sat quietly as cast and crew members approached his chair and sought instruction. My USC class got in by virtue of some tie-in the school had with the studio. After forty or so minutes, he walked over and called Action on a garage set with Karen Black and another actor. That was the summer of 1975.

A lot of us saw our first Hitchcocks on NBC Saturday Night At The Movies. That’s where I encountered Rear Window, Vertigo, and The Man Who Knew Too Much. CBS premiered North By Northwest in 1968. What a night. We never dreamed so many of these would disappear shortly thereafter. Hitchcock had a deal with Paramount that called for negatives to revert to him after a specified period. Rear Window, The Trouble With Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo (along with a Warners release, Rope) were in lock-up by the mid-seventies. You couldn’t see them (legitimately) anywhere. I remember small ads in Variety around that time offering rights to them. I assume those were run by Hitchcock’s representatives. The asking price must have been prohibitive during his lifetime. All five negatives were said to have been improperly stored. The restorations that took place years later were all the more difficult because of this. For all I know, Hitch had the things shoved to a corner in his wine cellar. 16mm collectors occasionally ran across prints that had once been rented by Films, Inc. Most of these were three-color Technicolor originals. You can imagine how coveted they were. A friend of mine bootlegged a negative of Rear Window from one of these treasures. It looked almost as good as the real thing. Being able to exhibit this one at your party in 1981 was quite the status symbol. A few years later, Universal bought the titles from Hitchcock’s estate and ground out ugly prints no better than our pirated ones, but we chased after them anyway. A lot of these were done for airline showings (they were still running 16mm on planes in the eighties!), and sometimes we’d run across three or four copies of Vertigo shoved under a dealer’s table at a collector’s show. The price? As with Xanadu, no man can say, but generally anywhere from $600 up, and this for a yellowish blur on a full-framed mockery of the intended Vistavision frame. But why go on rambling about the old days of film collecting when we can buy a superb rendition of Vertigo on DVD for a mere ten spot?

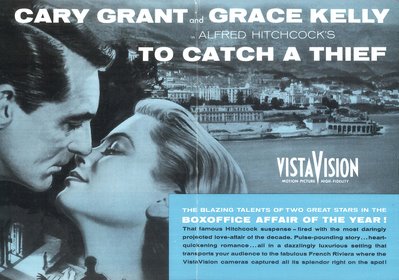

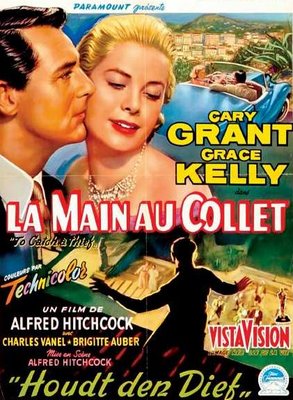

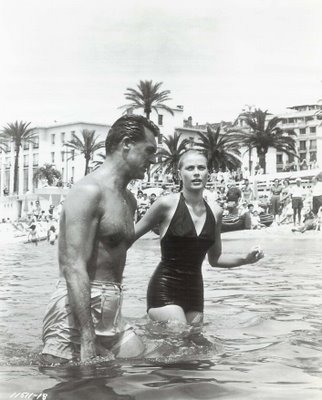

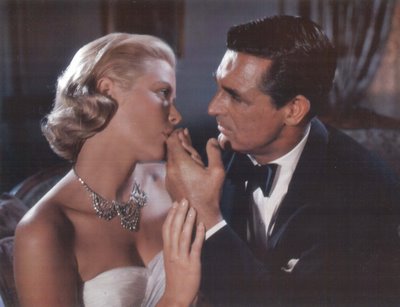

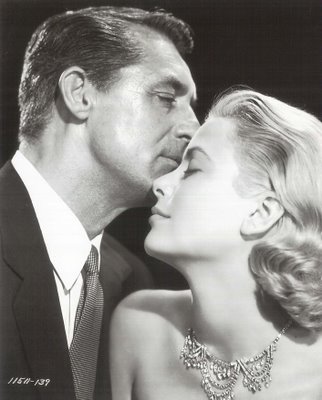

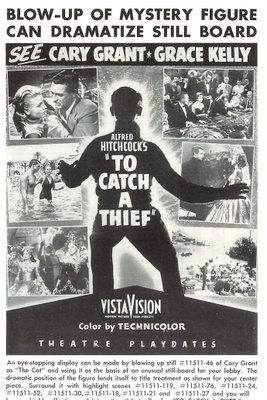

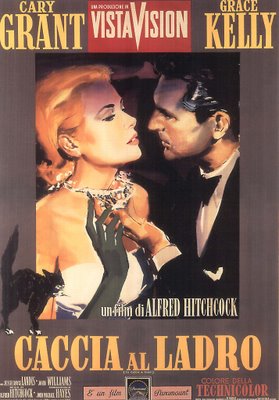

I decided to tackle To Catch A Thief for today’s Blog-A-Thon (why do I keep wanting to type It Takes A Thief? --- I never even watched the old Robert Wagner series). This movie has never come in for much analysis. I’ve not seen charts, graphs, nor blueprints in any of those academic explorations on Hitchcock. People call it eye candy. I’m still surprised and delighted at seeing Hitchcock’s cameo --- I mean, actually seeing it after all those years of being cropped out on television and rental prints. Remember how that was? Cary Grant would look over on the bus at --- nothing. I checked my clock a third of the way in and realized Grace Kelly hadn’t shown up yet, other than a glimpse on the beach. Much of that waiting was spent with yards of exposition. How many times must Cary assure us he’s not the Cat? John Williams sums up the whole thing at one point --- It’s a kind of travel folder heaven where a man dreams he’ll go when he retires. Imagine that Vistavision banquet audiences enjoyed in 1955. Paramount had already done a series of two-reel travelogues using the process. This was essentially the same deal, only it ran 106 minutes. Suspense takes a back seat to sport cars and overlooks. Lots of kissing goes on here. Hitchcock was clearly infatuated with Grace Kelly. Having complained previously about Cary Grant and his chicken leg (HERE), I’ll not revisit that. If any stars can get by without a story, it’s these two. Yes, even at my advanced age, I find that fireworks encounter pretty intoxicating. There must have been a lot of boomer infants conceived in the wake of dates to see this movie. To look at the confidence Grant displays, you marvel all the more at stories of how fussy and uncertain he could be on the set, but perfectionism asserts itself in different ways. For C.G., it seems to have resulted in parts turned down that one regrets all the more in hindsight, but I for one would hate to lose Humphrey Bogart as Linus Larabee. Still, what if Cary had done Sabrina? His good-will outreach during a publicity tour for To Catch A Thief confirmed Grant’s position as a favorite among showmen, as illustrated by this photo of him with Vancouver theatre-men. Regret to say I got an uneasy sensation watching Grace Kelly behind the wheel on a twisting Riviera byway, knowing the fate that awaited her decades later on that selfsame road. Was any director so enamoured of process shooting as Hitchcock? They didn’t spend a minute longer on that location than was necessary.

I decided to tackle To Catch A Thief for today’s Blog-A-Thon (why do I keep wanting to type It Takes A Thief? --- I never even watched the old Robert Wagner series). This movie has never come in for much analysis. I’ve not seen charts, graphs, nor blueprints in any of those academic explorations on Hitchcock. People call it eye candy. I’m still surprised and delighted at seeing Hitchcock’s cameo --- I mean, actually seeing it after all those years of being cropped out on television and rental prints. Remember how that was? Cary Grant would look over on the bus at --- nothing. I checked my clock a third of the way in and realized Grace Kelly hadn’t shown up yet, other than a glimpse on the beach. Much of that waiting was spent with yards of exposition. How many times must Cary assure us he’s not the Cat? John Williams sums up the whole thing at one point --- It’s a kind of travel folder heaven where a man dreams he’ll go when he retires. Imagine that Vistavision banquet audiences enjoyed in 1955. Paramount had already done a series of two-reel travelogues using the process. This was essentially the same deal, only it ran 106 minutes. Suspense takes a back seat to sport cars and overlooks. Lots of kissing goes on here. Hitchcock was clearly infatuated with Grace Kelly. Having complained previously about Cary Grant and his chicken leg (HERE), I’ll not revisit that. If any stars can get by without a story, it’s these two. Yes, even at my advanced age, I find that fireworks encounter pretty intoxicating. There must have been a lot of boomer infants conceived in the wake of dates to see this movie. To look at the confidence Grant displays, you marvel all the more at stories of how fussy and uncertain he could be on the set, but perfectionism asserts itself in different ways. For C.G., it seems to have resulted in parts turned down that one regrets all the more in hindsight, but I for one would hate to lose Humphrey Bogart as Linus Larabee. Still, what if Cary had done Sabrina? His good-will outreach during a publicity tour for To Catch A Thief confirmed Grant’s position as a favorite among showmen, as illustrated by this photo of him with Vancouver theatre-men. Regret to say I got an uneasy sensation watching Grace Kelly behind the wheel on a twisting Riviera byway, knowing the fate that awaited her decades later on that selfsame road. Was any director so enamoured of process shooting as Hitchcock? They didn’t spend a minute longer on that location than was necessary.

For me, it always comes back to the plight of the poor exhibitor. This time, they’d gone to war with Paramount over usurious terms on new releases. Every time a showman got out from under one screwing, another was poised to take its place. Paramount ranked second among distributors they loved to hate in 1955 (Warner Bros. was number one!). Harrison’s Reports was the straight-talking voice of disgruntled theatre-owners whose houses were near the point of closure in the wake of declining profits. Cinemascope provided a shot in the arm, but by August of 1955, when To Catch A Thief was released, that novelty had largely worn off, and it was back to bread and water for most small venues. Paramount seemed to offer a lifeline when it promised to address problems affecting exhibition, particularly theatres on the borderline of continued operation. Pete Harrison assured his readers that it was a lot of double-talk. "Distress" assistance seemed limited to those theatres already on the ropes, according to Harrison. Before you can expect relief from Paramount, it will be necessary for you to first "attain" the status of a pauper. Many theatres were struggling on receipts of less than a thousand per week. To Catch A Thief was being sold on a 50% basis, as were most major pictures of that year. It would be at least sixty days after release before they’d drop down to 35%, but that was long after the initial publicity build-up has worn down, according to theatre owners. Hitchcock’s film brought back domestic rentals of four million against negative costs of 2.8. Rear Window had performed better (4.8 million), though To Catch A Thief would top subsequent films from the director, The Trouble With Harry (a significant loss with only one million in domestic rentals) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (3.5). A 1963 re-issue of To Catch A Thief, which billed Cary Grant and "Princess" Grace Kelly, returned an additional $293,000. Unlike the other Paramount Hitchcocks, this negative remained with the distributor. It is the only one of the group not presently owned by Universal.