skip to main |

skip to sidebar

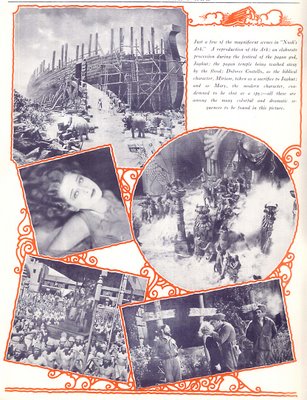

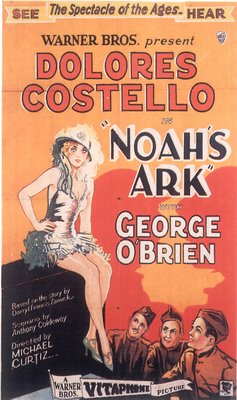

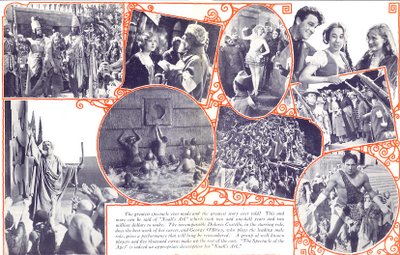

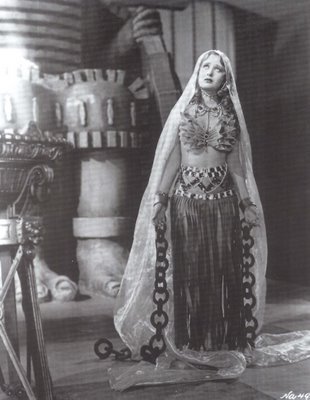

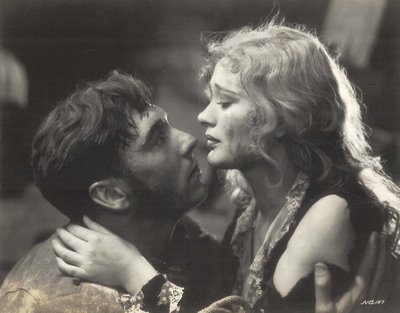

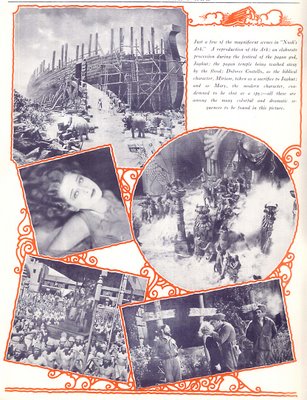

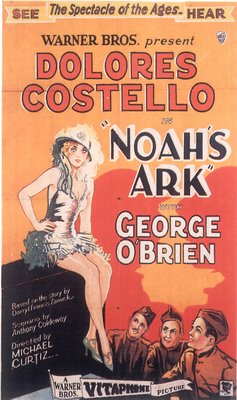

Life Was Cheap On Noah's Ark Once upon a time there were epics like Noah’s Ark. So many, in fact, that we took them for granted. This particular one cost a million dollars and at least two lives. The money spent was well publicized. Those who died or were injured were not. Names as well as their specific fates are unknown today. One man was said to have lost a leg. None of this story got out at the time. Whatever documentation arose from the incident was no doubt purged from studio files long ago. It’s often said they got away with murder in Hollywood --- here’s a show to back up that assertion. Director Michael Curtiz turned massive drums of water loose on 5000 screaming extras, and it was every man for himself. In a latter day landscape faked up with computer generated cataclysms, it’s truly startling to see a real flood enacted on screen, with people actually struggling for their lives. I got fascinated with this movie all over again while looking into Dolores Costello’s career with Warner Bros. She still remembered the horror of Noah’s Ark fifty years after it was completed. Mud, Blood, and Flood was what she called it. Wounded extras laid outside her dressing room door as fleets of ambulances carried away victims of the carnage. It must have taken some adroit handling on Warners' part to keep all this under wraps.

Life Was Cheap On Noah's Ark Once upon a time there were epics like Noah’s Ark. So many, in fact, that we took them for granted. This particular one cost a million dollars and at least two lives. The money spent was well publicized. Those who died or were injured were not. Names as well as their specific fates are unknown today. One man was said to have lost a leg. None of this story got out at the time. Whatever documentation arose from the incident was no doubt purged from studio files long ago. It’s often said they got away with murder in Hollywood --- here’s a show to back up that assertion. Director Michael Curtiz turned massive drums of water loose on 5000 screaming extras, and it was every man for himself. In a latter day landscape faked up with computer generated cataclysms, it’s truly startling to see a real flood enacted on screen, with people actually struggling for their lives. I got fascinated with this movie all over again while looking into Dolores Costello’s career with Warner Bros. She still remembered the horror of Noah’s Ark fifty years after it was completed. Mud, Blood, and Flood was what she called it. Wounded extras laid outside her dressing room door as fleets of ambulances carried away victims of the carnage. It must have taken some adroit handling on Warners' part to keep all this under wraps.

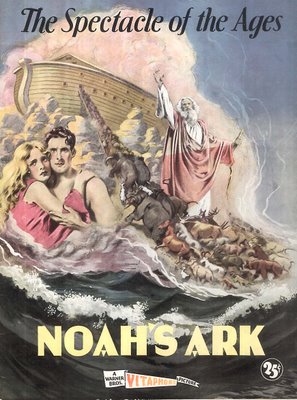

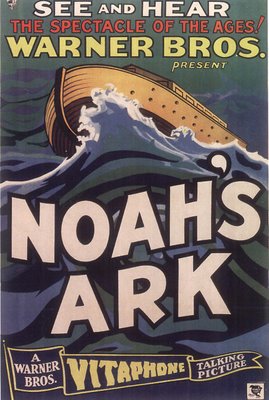

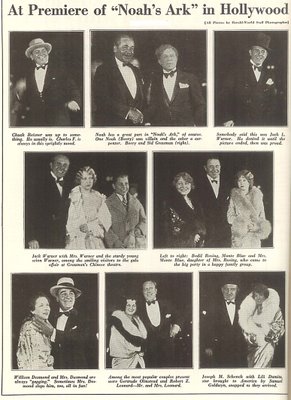

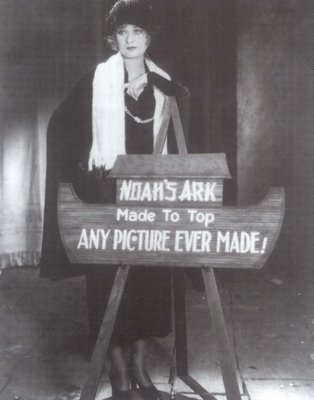

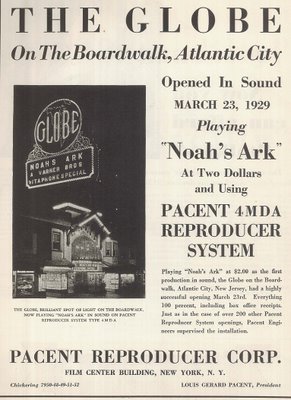

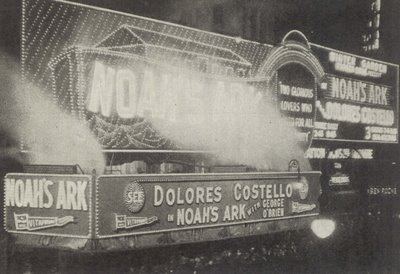

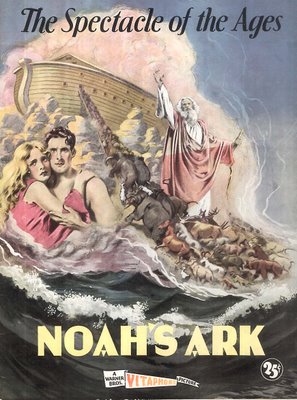

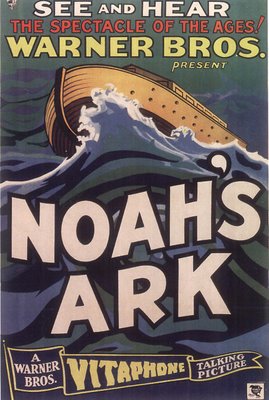

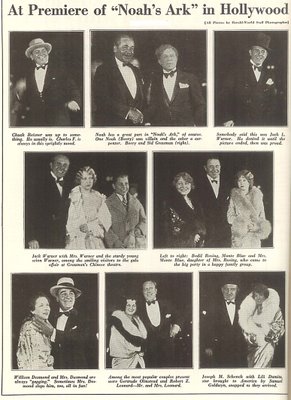

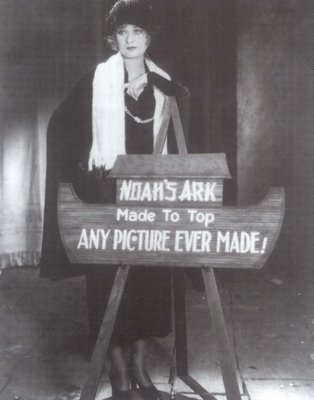

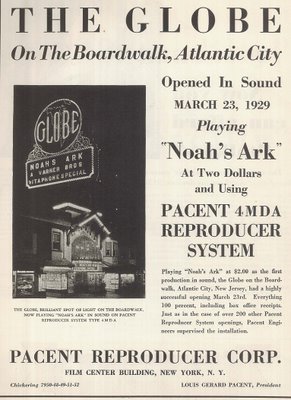

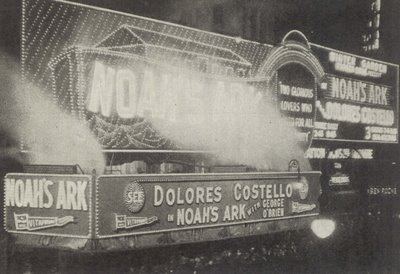

Noah’s Ark was designed for all-out showmanship. The show started outside New York’s Winter Garden Theatre with lighted displays and a forty-foot blimp hovering over the marquee. Eight "sunlight arcs" poured changing colors on the leviathan as wires caused it to dip and sway toward a giant replica of the ark electrified with rain effects and clouds of steam. Inside the auditorium, more deluge greeted the audience as wind and water signaled the Vitaphone overture. First-nighters paid eleven dollars a seat, and all were filled. Subsequent tickets went for two dollars, which caused resentment among reviewers whose own lukewarm response to Noah’s Ark was in part a rebuke of Warners for having oversold what these critics considered an ordinary and derivative picture. Seventy-seven years have a way of changing perspectives however --- were it remade today, Noah’s Ark would no doubt invite all sorts of controversy, considering the social agenda set forth in its dynamic opening reel. After a sobering glimpse of biblical era excesses, we’re treated to a montage of jazz age depravity. The Worship of the Golden Calf Remains Man’s Religion is the title preceding a frenzied day on Wall Street, where barter and loss of fortunes result in bloodshed on front steps of the exchange. Is this chaos and immorality a natural consequence of capitalism gone mad? Further dissolves depicting suicide, prostitution, and alcohol abuse suggests it is. Here’s a society badly in need of overhaul --- and this was months before the crash. Was Warners looking into a crystal ball? Theirs is a merciless commentary. Skyscrapers are modern Towers of Babel. America’s headed down a ticker tape highway to hell. If anyone tried selling a philosophy like this today, the very least they’d get is a good media spank for playing politics. Unsubtle as it is, Noah’s Ark packs a mean wallop with that opening, so much so that we’re almost sorry to see it veer off into a more prosaic World War One story for the hour or so that follows.

Noah’s Ark was designed for all-out showmanship. The show started outside New York’s Winter Garden Theatre with lighted displays and a forty-foot blimp hovering over the marquee. Eight "sunlight arcs" poured changing colors on the leviathan as wires caused it to dip and sway toward a giant replica of the ark electrified with rain effects and clouds of steam. Inside the auditorium, more deluge greeted the audience as wind and water signaled the Vitaphone overture. First-nighters paid eleven dollars a seat, and all were filled. Subsequent tickets went for two dollars, which caused resentment among reviewers whose own lukewarm response to Noah’s Ark was in part a rebuke of Warners for having oversold what these critics considered an ordinary and derivative picture. Seventy-seven years have a way of changing perspectives however --- were it remade today, Noah’s Ark would no doubt invite all sorts of controversy, considering the social agenda set forth in its dynamic opening reel. After a sobering glimpse of biblical era excesses, we’re treated to a montage of jazz age depravity. The Worship of the Golden Calf Remains Man’s Religion is the title preceding a frenzied day on Wall Street, where barter and loss of fortunes result in bloodshed on front steps of the exchange. Is this chaos and immorality a natural consequence of capitalism gone mad? Further dissolves depicting suicide, prostitution, and alcohol abuse suggests it is. Here’s a society badly in need of overhaul --- and this was months before the crash. Was Warners looking into a crystal ball? Theirs is a merciless commentary. Skyscrapers are modern Towers of Babel. America’s headed down a ticker tape highway to hell. If anyone tried selling a philosophy like this today, the very least they’d get is a good media spank for playing politics. Unsubtle as it is, Noah’s Ark packs a mean wallop with that opening, so much so that we’re almost sorry to see it veer off into a more prosaic World War One story for the hour or so that follows.

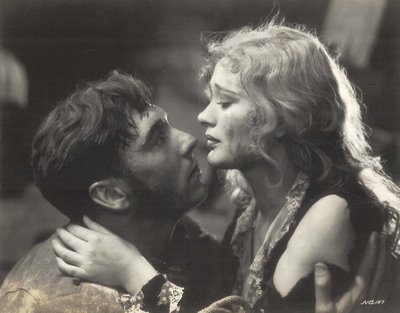

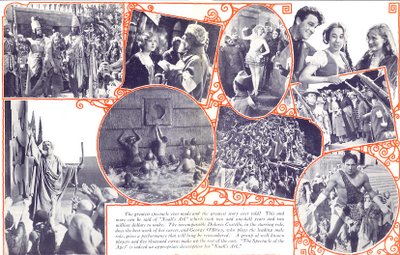

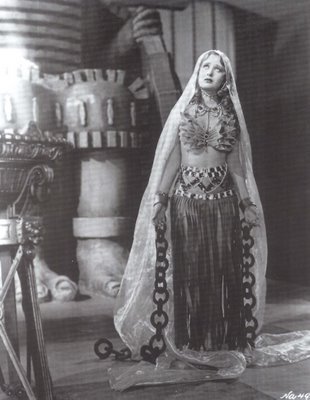

That wartime and biblical stuff rang a bell for 1929 audiences. They’d seen most of it before in The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Big Parade, and any number of inbred blockbusters that had so far racked up huge grosses. Noah’s Ark never pretended to be anything other than grand spectacle. What it stole would later be stolen from it. Pagan soldiers burn out George O’Brien’s eyes and bind him to a gristmill. DeMille got even for Warners’ pillage from his own biblical epics by lifting this plot device wholesale and using it in Samson and Delilah --- twenty years hence. Producers knew better than to be too original with this sort of material --- patrons came with certain expectations and expected them to be met. In Noah's Ark, trains are wrecked, maidens are abducted, and villains die horribly. Truly an exhibitor’s dream picture. Even against that million dollar negative (Warner’s biggest outlay as of that year), there was a profit of $523,000. Foreign sales were stimulated when director Michael Curtiz appeared on camera and narrated a series of Vitaphone trailers (in the appropriate language) for Hungarian, French, German, and Austrian theatres. Dialogue sequences spurred the domestic boxoffice. Isolated here and there, and accomplishing nothing other than bringing the narrative to a dead halt, they were a necessary evil and useful sop for fans expecting at least a little recorded bang for their buck. Poor Dolores Costello once again took a critical rapping (emotionless, stilted delivery), but the climactic flood more than put over the sock everyone had paid to see. For all his culpability regarding those doomed extras, Curtiz surely knew how to construct his epics. What a shame this Noah’s Ark had to run aground for sixty years after its initial release. It’s only by way of UCLA’s restoration miracle that we now can now recapture some semblance of what audiences enjoyed in 1929.

That wartime and biblical stuff rang a bell for 1929 audiences. They’d seen most of it before in The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Big Parade, and any number of inbred blockbusters that had so far racked up huge grosses. Noah’s Ark never pretended to be anything other than grand spectacle. What it stole would later be stolen from it. Pagan soldiers burn out George O’Brien’s eyes and bind him to a gristmill. DeMille got even for Warners’ pillage from his own biblical epics by lifting this plot device wholesale and using it in Samson and Delilah --- twenty years hence. Producers knew better than to be too original with this sort of material --- patrons came with certain expectations and expected them to be met. In Noah's Ark, trains are wrecked, maidens are abducted, and villains die horribly. Truly an exhibitor’s dream picture. Even against that million dollar negative (Warner’s biggest outlay as of that year), there was a profit of $523,000. Foreign sales were stimulated when director Michael Curtiz appeared on camera and narrated a series of Vitaphone trailers (in the appropriate language) for Hungarian, French, German, and Austrian theatres. Dialogue sequences spurred the domestic boxoffice. Isolated here and there, and accomplishing nothing other than bringing the narrative to a dead halt, they were a necessary evil and useful sop for fans expecting at least a little recorded bang for their buck. Poor Dolores Costello once again took a critical rapping (emotionless, stilted delivery), but the climactic flood more than put over the sock everyone had paid to see. For all his culpability regarding those doomed extras, Curtiz surely knew how to construct his epics. What a shame this Noah’s Ark had to run aground for sixty years after its initial release. It’s only by way of UCLA’s restoration miracle that we now can now recapture some semblance of what audiences enjoyed in 1929.

Noah’s Ark’s initial deliverer was Robert Youngson, who’d championed the film during the early fifties when he was employed in Warner Bros.’ short subjects department. A lifelong film buff and later producer of all those fabulous comedy compilations, Youngson edited a group of one-reel subjects culled from silent spectaculars such as Don Juan, Isle Of Lost Ships, Old San Francisco, and Noah’s Ark. When Associated Artists bought the Warners pre-49 library for television release in 1956, they ended up with the surviving silent negatives as well, including Noah’s Ark. While 16mm prints were being prepared for TV sales, AAP established a subsidiary called Dominant Pictures, whose mission was to squeeze whatever theatrical bookings they could out of the old Warner product before the video dump. Youngson approached Dominant with his idea of re-editing and "modernizing" Noah’s Ark for a 35mm re-issue. Since they now owned the picture anyway, there was little to lose. The 1957 version would be shorn of all intertitles and talking sequences. Newsreel narrator Dwight Weist provided non-stop explanation and commentary throughout a truncated Noah’s Ark, but this was all the access we’d have to the film until Robert Gitt and the UCLA restoration team got hold of the project in 1988. What’s now shown regularly on TCM is their handiwork, and other than a little missing footage here and there, it’s the complete 1929 general release version. If ever there was a title worth canvassing your TCM schedule for, Noah’s Ark is it. I’d like to think there’s a DVD release somewhere in the offing as well. The definitive production and restoration history of Noah's Ark was written by Scott MacQueen and published in Issue 12 (Winter 1991-92) of The Perfect Vision. A great piece of scholarship and highly recommended.

Noah’s Ark’s initial deliverer was Robert Youngson, who’d championed the film during the early fifties when he was employed in Warner Bros.’ short subjects department. A lifelong film buff and later producer of all those fabulous comedy compilations, Youngson edited a group of one-reel subjects culled from silent spectaculars such as Don Juan, Isle Of Lost Ships, Old San Francisco, and Noah’s Ark. When Associated Artists bought the Warners pre-49 library for television release in 1956, they ended up with the surviving silent negatives as well, including Noah’s Ark. While 16mm prints were being prepared for TV sales, AAP established a subsidiary called Dominant Pictures, whose mission was to squeeze whatever theatrical bookings they could out of the old Warner product before the video dump. Youngson approached Dominant with his idea of re-editing and "modernizing" Noah’s Ark for a 35mm re-issue. Since they now owned the picture anyway, there was little to lose. The 1957 version would be shorn of all intertitles and talking sequences. Newsreel narrator Dwight Weist provided non-stop explanation and commentary throughout a truncated Noah’s Ark, but this was all the access we’d have to the film until Robert Gitt and the UCLA restoration team got hold of the project in 1988. What’s now shown regularly on TCM is their handiwork, and other than a little missing footage here and there, it’s the complete 1929 general release version. If ever there was a title worth canvassing your TCM schedule for, Noah’s Ark is it. I’d like to think there’s a DVD release somewhere in the offing as well. The definitive production and restoration history of Noah's Ark was written by Scott MacQueen and published in Issue 12 (Winter 1991-92) of The Perfect Vision. A great piece of scholarship and highly recommended.

Life Was Cheap On Noah's Ark Once upon a time there were epics like Noah’s Ark. So many, in fact, that we took them for granted. This particular one cost a million dollars and at least two lives. The money spent was well publicized. Those who died or were injured were not. Names as well as their specific fates are unknown today. One man was said to have lost a leg. None of this story got out at the time. Whatever documentation arose from the incident was no doubt purged from studio files long ago. It’s often said they got away with murder in Hollywood --- here’s a show to back up that assertion. Director Michael Curtiz turned massive drums of water loose on 5000 screaming extras, and it was every man for himself. In a latter day landscape faked up with computer generated cataclysms, it’s truly startling to see a real flood enacted on screen, with people actually struggling for their lives. I got fascinated with this movie all over again while looking into Dolores Costello’s career with Warner Bros. She still remembered the horror of Noah’s Ark fifty years after it was completed. Mud, Blood, and Flood was what she called it. Wounded extras laid outside her dressing room door as fleets of ambulances carried away victims of the carnage. It must have taken some adroit handling on Warners' part to keep all this under wraps.

Life Was Cheap On Noah's Ark Once upon a time there were epics like Noah’s Ark. So many, in fact, that we took them for granted. This particular one cost a million dollars and at least two lives. The money spent was well publicized. Those who died or were injured were not. Names as well as their specific fates are unknown today. One man was said to have lost a leg. None of this story got out at the time. Whatever documentation arose from the incident was no doubt purged from studio files long ago. It’s often said they got away with murder in Hollywood --- here’s a show to back up that assertion. Director Michael Curtiz turned massive drums of water loose on 5000 screaming extras, and it was every man for himself. In a latter day landscape faked up with computer generated cataclysms, it’s truly startling to see a real flood enacted on screen, with people actually struggling for their lives. I got fascinated with this movie all over again while looking into Dolores Costello’s career with Warner Bros. She still remembered the horror of Noah’s Ark fifty years after it was completed. Mud, Blood, and Flood was what she called it. Wounded extras laid outside her dressing room door as fleets of ambulances carried away victims of the carnage. It must have taken some adroit handling on Warners' part to keep all this under wraps.

Noah’s Ark was designed for all-out showmanship. The show started outside New York’s Winter Garden Theatre with lighted displays and a forty-foot blimp hovering over the marquee. Eight "sunlight arcs" poured changing colors on the leviathan as wires caused it to dip and sway toward a giant replica of the ark electrified with rain effects and clouds of steam. Inside the auditorium, more deluge greeted the audience as wind and water signaled the Vitaphone overture. First-nighters paid eleven dollars a seat, and all were filled. Subsequent tickets went for two dollars, which caused resentment among reviewers whose own lukewarm response to Noah’s Ark was in part a rebuke of Warners for having oversold what these critics considered an ordinary and derivative picture. Seventy-seven years have a way of changing perspectives however --- were it remade today, Noah’s Ark would no doubt invite all sorts of controversy, considering the social agenda set forth in its dynamic opening reel. After a sobering glimpse of biblical era excesses, we’re treated to a montage of jazz age depravity. The Worship of the Golden Calf Remains Man’s Religion is the title preceding a frenzied day on Wall Street, where barter and loss of fortunes result in bloodshed on front steps of the exchange. Is this chaos and immorality a natural consequence of capitalism gone mad? Further dissolves depicting suicide, prostitution, and alcohol abuse suggests it is. Here’s a society badly in need of overhaul --- and this was months before the crash. Was Warners looking into a crystal ball? Theirs is a merciless commentary. Skyscrapers are modern Towers of Babel. America’s headed down a ticker tape highway to hell. If anyone tried selling a philosophy like this today, the very least they’d get is a good media spank for playing politics. Unsubtle as it is, Noah’s Ark packs a mean wallop with that opening, so much so that we’re almost sorry to see it veer off into a more prosaic World War One story for the hour or so that follows.

Noah’s Ark was designed for all-out showmanship. The show started outside New York’s Winter Garden Theatre with lighted displays and a forty-foot blimp hovering over the marquee. Eight "sunlight arcs" poured changing colors on the leviathan as wires caused it to dip and sway toward a giant replica of the ark electrified with rain effects and clouds of steam. Inside the auditorium, more deluge greeted the audience as wind and water signaled the Vitaphone overture. First-nighters paid eleven dollars a seat, and all were filled. Subsequent tickets went for two dollars, which caused resentment among reviewers whose own lukewarm response to Noah’s Ark was in part a rebuke of Warners for having oversold what these critics considered an ordinary and derivative picture. Seventy-seven years have a way of changing perspectives however --- were it remade today, Noah’s Ark would no doubt invite all sorts of controversy, considering the social agenda set forth in its dynamic opening reel. After a sobering glimpse of biblical era excesses, we’re treated to a montage of jazz age depravity. The Worship of the Golden Calf Remains Man’s Religion is the title preceding a frenzied day on Wall Street, where barter and loss of fortunes result in bloodshed on front steps of the exchange. Is this chaos and immorality a natural consequence of capitalism gone mad? Further dissolves depicting suicide, prostitution, and alcohol abuse suggests it is. Here’s a society badly in need of overhaul --- and this was months before the crash. Was Warners looking into a crystal ball? Theirs is a merciless commentary. Skyscrapers are modern Towers of Babel. America’s headed down a ticker tape highway to hell. If anyone tried selling a philosophy like this today, the very least they’d get is a good media spank for playing politics. Unsubtle as it is, Noah’s Ark packs a mean wallop with that opening, so much so that we’re almost sorry to see it veer off into a more prosaic World War One story for the hour or so that follows.

That wartime and biblical stuff rang a bell for 1929 audiences. They’d seen most of it before in The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Big Parade, and any number of inbred blockbusters that had so far racked up huge grosses. Noah’s Ark never pretended to be anything other than grand spectacle. What it stole would later be stolen from it. Pagan soldiers burn out George O’Brien’s eyes and bind him to a gristmill. DeMille got even for Warners’ pillage from his own biblical epics by lifting this plot device wholesale and using it in Samson and Delilah --- twenty years hence. Producers knew better than to be too original with this sort of material --- patrons came with certain expectations and expected them to be met. In Noah's Ark, trains are wrecked, maidens are abducted, and villains die horribly. Truly an exhibitor’s dream picture. Even against that million dollar negative (Warner’s biggest outlay as of that year), there was a profit of $523,000. Foreign sales were stimulated when director Michael Curtiz appeared on camera and narrated a series of Vitaphone trailers (in the appropriate language) for Hungarian, French, German, and Austrian theatres. Dialogue sequences spurred the domestic boxoffice. Isolated here and there, and accomplishing nothing other than bringing the narrative to a dead halt, they were a necessary evil and useful sop for fans expecting at least a little recorded bang for their buck. Poor Dolores Costello once again took a critical rapping (emotionless, stilted delivery), but the climactic flood more than put over the sock everyone had paid to see. For all his culpability regarding those doomed extras, Curtiz surely knew how to construct his epics. What a shame this Noah’s Ark had to run aground for sixty years after its initial release. It’s only by way of UCLA’s restoration miracle that we now can now recapture some semblance of what audiences enjoyed in 1929.

That wartime and biblical stuff rang a bell for 1929 audiences. They’d seen most of it before in The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Big Parade, and any number of inbred blockbusters that had so far racked up huge grosses. Noah’s Ark never pretended to be anything other than grand spectacle. What it stole would later be stolen from it. Pagan soldiers burn out George O’Brien’s eyes and bind him to a gristmill. DeMille got even for Warners’ pillage from his own biblical epics by lifting this plot device wholesale and using it in Samson and Delilah --- twenty years hence. Producers knew better than to be too original with this sort of material --- patrons came with certain expectations and expected them to be met. In Noah's Ark, trains are wrecked, maidens are abducted, and villains die horribly. Truly an exhibitor’s dream picture. Even against that million dollar negative (Warner’s biggest outlay as of that year), there was a profit of $523,000. Foreign sales were stimulated when director Michael Curtiz appeared on camera and narrated a series of Vitaphone trailers (in the appropriate language) for Hungarian, French, German, and Austrian theatres. Dialogue sequences spurred the domestic boxoffice. Isolated here and there, and accomplishing nothing other than bringing the narrative to a dead halt, they were a necessary evil and useful sop for fans expecting at least a little recorded bang for their buck. Poor Dolores Costello once again took a critical rapping (emotionless, stilted delivery), but the climactic flood more than put over the sock everyone had paid to see. For all his culpability regarding those doomed extras, Curtiz surely knew how to construct his epics. What a shame this Noah’s Ark had to run aground for sixty years after its initial release. It’s only by way of UCLA’s restoration miracle that we now can now recapture some semblance of what audiences enjoyed in 1929.

Noah’s Ark’s initial deliverer was Robert Youngson, who’d championed the film during the early fifties when he was employed in Warner Bros.’ short subjects department. A lifelong film buff and later producer of all those fabulous comedy compilations, Youngson edited a group of one-reel subjects culled from silent spectaculars such as Don Juan, Isle Of Lost Ships, Old San Francisco, and Noah’s Ark. When Associated Artists bought the Warners pre-49 library for television release in 1956, they ended up with the surviving silent negatives as well, including Noah’s Ark. While 16mm prints were being prepared for TV sales, AAP established a subsidiary called Dominant Pictures, whose mission was to squeeze whatever theatrical bookings they could out of the old Warner product before the video dump. Youngson approached Dominant with his idea of re-editing and "modernizing" Noah’s Ark for a 35mm re-issue. Since they now owned the picture anyway, there was little to lose. The 1957 version would be shorn of all intertitles and talking sequences. Newsreel narrator Dwight Weist provided non-stop explanation and commentary throughout a truncated Noah’s Ark, but this was all the access we’d have to the film until Robert Gitt and the UCLA restoration team got hold of the project in 1988. What’s now shown regularly on TCM is their handiwork, and other than a little missing footage here and there, it’s the complete 1929 general release version. If ever there was a title worth canvassing your TCM schedule for, Noah’s Ark is it. I’d like to think there’s a DVD release somewhere in the offing as well. The definitive production and restoration history of Noah's Ark was written by Scott MacQueen and published in Issue 12 (Winter 1991-92) of The Perfect Vision. A great piece of scholarship and highly recommended.

Noah’s Ark’s initial deliverer was Robert Youngson, who’d championed the film during the early fifties when he was employed in Warner Bros.’ short subjects department. A lifelong film buff and later producer of all those fabulous comedy compilations, Youngson edited a group of one-reel subjects culled from silent spectaculars such as Don Juan, Isle Of Lost Ships, Old San Francisco, and Noah’s Ark. When Associated Artists bought the Warners pre-49 library for television release in 1956, they ended up with the surviving silent negatives as well, including Noah’s Ark. While 16mm prints were being prepared for TV sales, AAP established a subsidiary called Dominant Pictures, whose mission was to squeeze whatever theatrical bookings they could out of the old Warner product before the video dump. Youngson approached Dominant with his idea of re-editing and "modernizing" Noah’s Ark for a 35mm re-issue. Since they now owned the picture anyway, there was little to lose. The 1957 version would be shorn of all intertitles and talking sequences. Newsreel narrator Dwight Weist provided non-stop explanation and commentary throughout a truncated Noah’s Ark, but this was all the access we’d have to the film until Robert Gitt and the UCLA restoration team got hold of the project in 1988. What’s now shown regularly on TCM is their handiwork, and other than a little missing footage here and there, it’s the complete 1929 general release version. If ever there was a title worth canvassing your TCM schedule for, Noah’s Ark is it. I’d like to think there’s a DVD release somewhere in the offing as well. The definitive production and restoration history of Noah's Ark was written by Scott MacQueen and published in Issue 12 (Winter 1991-92) of The Perfect Vision. A great piece of scholarship and highly recommended.