The Idol Of Every Boy In The World

Tom Mix might have auditioned for Boris Karloff’s eventual role in Frankenstein. Physically qualified at the least, his body had been scarred, smashed-up, then held together by wiring through much of a fabulous career. Mix played cowboys at a time when movies provided no safe haven for western names looking to occupy that top rung. He got to be Number One by sheer dogged refusal to fake anything, thus week after month after year found him rolling off cliffs, dangling above ravines, leaping horseback over chasms … any and all feats not yet attempted and awaiting only Tom's willingness to jump in the fray and risk his fool neck all over again. For a staggering $17,500 a week, Mix broke legs, shattered shoulders, and bore concussions. All his teeth had been busted out through ill-timed horsefalls and punches various bad guys neglected to pull. The good showman in him required Tom to dress out in a rack of glistening store choppers fully capable of biting through flagpoles, though frequent bar-fights and drunken set-to's obliged him to replace these often. Sometimes, damage was collateral (one leading lady drowned on a Mix show), though rewards for a broken body were plentiful. That salary put Tom in a centrally air-conditioned mansion (in 1925!!), and with over 600 pairs of boots, there wasn’t a better-shod westerner in Hollywood (no, let’s make that the whole country). All this for a man who’d barely finished fifth-grade, but applied himself to reading the complete works of Shakespeare and consulting encyclopedias often so he wouldn’t be lost in conversation with formally educated friends and associates. Truly a self-made (and invented) Renaissance man of the west commanding an audience vast beyond the comprehension of modern-day faux celebrities and their niche followers. Kids loved Tom, but so did parents. They expected each show to be more thrilling than the last, and no one was counting the pounds of flesh Mix was expending to provide just that. The Monarch Of The Plains (so named by his studio) presided over this Roman coliseum through (some say) 336 films, though exact numbers are hard to pin down, so many being re-titled --- then lost --- thus the sketchy record of trails he rode. Tom would have better insured his safety as a lion tamer or bullfighter, for making western movies was for him like Russian Roulette with all six chambers loaded. His last was The Miracle Rider, well named as it was a miracle Tom could still ride, and this final curtain call at age fifty-five was proof if nothing else that he was truly King of those cowboys who knew how to live dangerously, both on and off the screen.

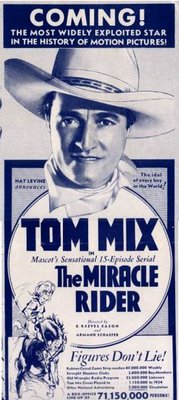

Producer Nat Levine dangled $40,000 before Mix for his pledge to top-line The Miracle Rider over a four-week shooting schedule. Nat’s Mascot Company was the go-to place for low-budget serials peddled on a State’s Rights basis (here’s the sales force posed amidst lobby displays for a 1933 offering, The Lost Jungle). Their doozy of a logo featured a Bengal tiger with paws draped over the world globe, roaring as those words Mascot Pictures encircled from the right. Kids must have cheered plenty when they saw that. Individual franchises would buy exclusive rights in Levine’s chapter-plays and squeeze whatever coin they could in distribution time allowed. Each serial was an individual crapshoot that could make or break Levine, but Tom Mix was the nearest to a sure thing he ever had. The cowboy legend was persuaded not only by Mascot's money (he'd recently bought a circus and needed to prop up those tents), but by Nat’s stealth appeal to his conservative notions regarding social issues. Criminals on the loose. Boys and girls learning Communist propaganda in schools --- these were anathema to Mix and a return to the screen would be his means of combating them. When Mascot Pictures Corporation showed me the story of "The Miracle Rider," I knew I had the kind of rip-snortin’, he-man chapter-play which would thrill every kid in town. Those fifteen installments would also help sustain interest in Tom’s circus, struggling to separate patrons from their hard-earned Depression change during a year when disposable income was at an absolute nadir. Levine spent $80,000 getting The Miracle Rider made (with half that gone to Mix), and hoped to increase bookings that had previously hovered between eight and nine thousand (Rider would end up with over 12,000 engagements). He put three units to work so as to speed production. One would shoot dialogue and interiors, with two more busy staging action and chase segments. Silent villain turned stuntman Cliff Lyons doubled for a star no longer able to withstand the rough tumbles. Tom had retired out of Universal three years earlier figuring his game was up. A burst appendix and near-fatal bout with peritonitis in 1931 was proof enough he might be mortal after all, but then as if to reassure himself otherwise, Mix cleaned out saloons over the Mexican border during re-laxation breaks between circus and vaudeville jobs. Those miles really told on him now. Jet black hair-dye fooled nobody, and dialogue that never came easy stuck in the throat which legend claims lodged a bullet fired during a surly exchange with wife number four (of five). Further investigation suggests she didn’t tag him throat-wise after all, but did put one in an arm that settled near Tom’s spine. It seemed wherever Mix went, lead was flying, with his living room no safer than riding in front of outlaw posses.

I’d respect Tom less if he recited lines better. Mangled words and halting delivery only enhance the man's credibility as far as I’m concerned. He knew elocution was for sissies. When Mix says secretary, it comes out sec-er-tary. He’ll stop in mid-sentence to ponder whatever the hell those words are supposed to be, surrender to faulty memory, then ad-lib something better and more authentic. The need for speed and Tom’s get-it-done impatience meant no retakes, so what we see in The Miracle Rider is fifteen glorious blooper reels where expecting the unexpected is half the fun. Minus that pesky talk, Mix offers a twilight glimpse of what he’d delivered back in the day. Running inserts are plentiful and that’s sure enough Tom riding Tony (Jr.). Charles Middleton plays a character named Zaroff; all we need to tip us off as to sinister intentions. Tame indians are being forced off the reservation so he can harvest X-94, an explosive so powerful you'd think it would come in something other than feed sacks and be tossed about so promiscuously. Texas Ranger and staunch friend to the red man Mix spends much of Chapters One and Two seeking fingerprints from an arrow discovered in the chief’s back, all of which made me wonder how you could get a useful print off an arrow. As with Mascot’s previous The Vanishing Legion, everything takes place in the present day, so there’s limousines parked beside tethered horses, something I always enjoy seeing. The dog heavies mount up in three-piece suits at one point to pass as "townspeople", chasing a western-garbed (and horsebacked) Mix in their business attire, while Tom’s wardrobe includes a ten gallon (times twenty) hat so majestic as to deserve a credit all its own. Sights like this are unique to the Mascot universe, and much to be savored. There’s a rocket glider called The Firebird, with a neat whistling sound to accompany flight, though I was disappointed in seeing it crash to earth after only two chapters. Modernistic, near sci-fi devices are utilized as though they were common household accessories. Cave hideouts have telephone extensions built into rock walls. Messages are received on television screens concealed behind paintings, while Middleton declares (often, and despite near-constant setbacks) he’ll soon be the most powerful man in the world. Apostle of fair play Tom never guns an opponent down. Pistols are shot out of miscreant’s hands, villains either roped or bulldogged, none seriously injured. Cheater endings sent my remote into reverse mode several times. I’d seen Mix blasted by a trap gun while opening a door at the end of Chapter Five, though he neatly sidestepped that same assault at the beginning of Chapter Six. Seems they’d shot the scene twice to mislead us. Twenty minutes later, horses trampled Tom as Chapter Six concluded, but Chapter Seven found him well clear of the stampede. Maybe a week’s passage helped kids forget such niggling details in 1935, though I’m betting a number of them cried Foul even then.

Nat Levine claimed grosses on The Miracle Rider amounted to one million, though his boosted (and boasted) estimate probably inflated the actual number by at least half. Still, no serial had done this well since Universal’s Tim McCoy special, The Indians Are Coming. Mix’s comeback amounted to a nostalgia trip for boys (now dads) who’d grown up with him in the teens and early twenties. Indeed, Tom may have been the first cowboy selling tickets to both kids and an older generation raised on the venerable star. Summer of 1935 found Nat Levine and Universal once again head to head for chapter-play bookings, but Buck Jones and The Roaring West was no match for Tom Mix. Soon after, Levine teamed with his lab supplier, Herbert Yates, along with Monogram and other states-rights small-timers, to form Republic Pictures, but it wouldn’t be long before Yates bought Nat out with a million cash. That would be the last million Levine would ever see, for within a few years, it was all sucked into betting windows at various tracks, leaving Mascot’s founder dead broke. Nat finally sold his negatives to a TV distributor in the late forties, and The Miracle Rider was among those very first serials experienced by home viewers. It fetched a princely $3000 for single runs during the early fifties, while Nat Levine retreated to management of a small theatre in Redondo Beach. He stayed there two decades, changing marquees and pasting ads. Interviewers got to him from time to time, but Nat chilled once he realized there'd be no money in the conversations. He died at the Motion Picture Country Home in 1989. For Tom Mix, The Miracle Rider was a final curtain call. His circus venture was largely dollars down a rathole. He had all the bad luck short of Lyle Bettger wrecking his train. Tom’s own $400,000 was sunk in the tents, and storms blew one of those away in 1936, then he faced assault charges after dusting it up with a heckler. Income from Ralston-Purina kept him out of bankruptcy. They sponsored the radio show featuring Tom’s name and character, but not Tom. 140 premiums (Straight Shooter’s Secret Club Manuals, glow-in-the-dark belts, etc.) were sold to Mix-mad listeners over a near-twenty year period the show lasted (here he is sharing Ralston cereal with a fan). By the end of its run in 1950, Tom himself was gone a decade, having launched his sport convertible into a ravine far less imposing than those he'd effortlessly leaped but a generation before. He was sixty.

Two great books about Mix and Mascot. Robert Birchard's Tom Mix --- King Cowboy is the last word on the western star, and Birchard's about the best researcher in the business. The Vanishing Legion is Jon Tuska's definitive history of Nat Levine and Mascot.

A couple of new images, links, polishes, etc. on Gail Russell and The Lost Patrol in Greenbriar's archives.