Jean Harlow --- Part Two

Jean Harlow --- Part TwoCode enforcement signaled the end for Jean Harlow’s established image as surely as it had for Mae West. The character may have been played out in any case, but clearly something had to be done to accommodate the Code and maintain Harlow as a viable ongoing attraction. Hold Your Man was produced and released before the crackdown of mid-1934, but already MGM was softening content, perhaps in response to outcry over Red Dust. This second Gable/Harlow co-starring vehicle was like two wildly disparate movies under a single wobbly umbrella. The first thirty-five or so minutes was bare knuckle pre-code hijinks we could all appreciate (and still do), but that final half doled out excessive punishment to both the actors and their audience, as if to chastise us for having enjoyed what went before. It was a harbinger of worse things to come, not only for Jean Harlow but for a generation of actresses who’d defined themselves in terms of pre-code freedom of expression. Things would never be the same for any of them after this. The Girl From Missouri was the final selection from a menu of titles --- Born To Be Kissed clearly wouldn’t do under the new order, 100% Pure was someone's idea of sarcasm, while Eadie Was A Lady sounded like a Stay Home warning to Harlow’s fan following. August 1934 was the release date, and The Girl From Missouri proudly displayed its PCA seal before the opening credits, assurance for local censors otherwise inclined to apply their own scissors. We’re briefed within minutes as to the rules, and by Harlow herself. I have ideals … I’m a lady … etcetera … a whole new declaration of principles from an actress whose characters had gotten along nicely without them. Harlow was swimming against a new tide, and 1934 audiences had to wonder if they weren’t being sold mislabeled product.

It was a testament to her public’s confidence that Harlow maintained popularity despite the neutering, though a $125,000 loss on Reckless and $63,000 down with Riff-Raff suggested patience might be wearing thin. Metro’s answer was to polish off some rough edges. First, the hair had to change, which was good because it was nearly gone anyway, having been coarsened and ruined over years of mistreatment. The new brownette look went hand in hand with gentler Jean, no longer the barbed wire that wrapped herself around leading men, but an unassuming helpmate, best exemplified by a subdued turn in Wife vs. Secretary. This was 1936, and the adulterous games she’d played onscreen during pre-code years was now a deadly serious business with grave consequences for those who transgressed. Jean’s secretary was a nice girl living at home with Mom and Dad, her gelded suitor a just beginning James Stewart. Whatever sizzle audiences recalled with co-star Clark Gable was lost in the mists of time, as PCA prohibitions against re-issues of forbidden titles kept embargoes firmly in place. Harlow’s compensation was now increased ($3,000 a week), but the suffocating mother was a continuing problem, and the star never girded up sufficient will to fight back. Alcohol became the hidden crutch, though it seldom interfered with work, but what about nagging health problems that plagued her? Impacted wisdom teeth led to a procedure that almost proved fatal, and photographers who’d once tabbed hers the flawless face and figure now applied retouching to both. Romance with urbane William Powell held the promise of eternal commitment, only Bill didn't want to commit, and that resulted in public embarrassment for Jean. This was the world’s most desirable woman, after all.

The image modification seemed to have worked. Profits for the next several were up. Suzy ($498,000), Libeled Lady (1.1 million), and Personal Property ($872,000) promised glad tidings to come. Jean was still young enough to sustain at least another decade of success, unlike older thoroughbreds in Metro stables. As Shearer, Crawford, and Garbo were maturing out, Harlow ascended to first chair among female talent. A forthcoming loan to Fox for their spectacular In Old Chicago promised to team her with man of the hour Tyrone Power. That she would die at this moment was unimaginable, but that’s what happened on June 7, 1937. Her kidneys had been degenerating since that scarlet fever episode in 1926. The crisis point was upon her and nothing could undo years of cumulative damage. A lot of friends and co-workers blamed the crazy mother and her Christian Science-inspired determination to avoid doctors, but Mayo Clinic couldn’t have saved this girl. The shock was all the more palpable because Harlow was genuinely liked among peers, and no one imagined such a dire outcome for her. Death was lingering and painful. The official cause was uremic poisoning --- total organ shutdown and a ghoulish tableau for visitors they’d never get over. She was just 26.

Would Jean Harlow have sustained her popularity into the forties? You ask these questions when pondering the Valentinos, Lombards, Deans, Monroes --- all those who exited early and took promise with them. I suspect Harlow would have aged uncomfortably. She might have been fated to play June Allyson or Gloria DeHaven’s mother, maybe in one of those wartime boosters where she objects to Van Johnson as a suitor or helps put on a camp show with Gene Kelly. Would they have made her do a Lassie? Reunions with Clark Gable would have been unlikely with Lana Turner about, unless it was a character cameo like Mary Astor had with him in Any Number Can Play. Imagine Harlow doing television --- teaming up with Robert Taylor on an episode of The Detectives for old time’s sake. Sometimes a long life isn’t necessarily the best life when it comes to preserving myths. Harlow’s was shattered, then rebuilt, on several occasions after her death. Iconic status was immediately conferred with Metro’s posthumous release of the unfinished Saratoga, which offered the spectacle of both Jean’s final footage and a name-that-double exercise in studio sleight-of-hand. The girl standing in behind glasses, binoculars, and floppy hat was Mary Dees, who died only last year after (nearly) seventy years refusal to discuss Saratoga. Was she haunted by Harlow’s restless spirit? Opportunistic re-issues supplied their own post-mortem. Hell’s Angels was back, but much of her footage was trimmed, while Columbia sustained interest with a Platinum Blonde revival in the late forties. The big noise arrived in the sixties, when writer Irving Schulman offered up a largely fictionalized bio that lit the fuse of many Harlow co-workers who’d loudly declare his perfidy. Even long retired William Powell issued a statement. Two movies were adapted from Shulman’s speculations, but the three million in domestic rentals Paramount realized from its Harlow had to have been a disappointment for them. A few of Jean’s originals made theatrical rounds as well, but Red Dust and Dinner At Eight were mostly there for a handful of repertory bookings and old-timer matinees. The real Harlow comeback would have to wait for TCM and home video, and here was where long buried treasures like Beast Of The City and Libeled Lady reasserted their presence among fans. As for DVD prospects, Red-Headed Woman is slated for next month, and word is a Harlow box will follow.

Photo Captions

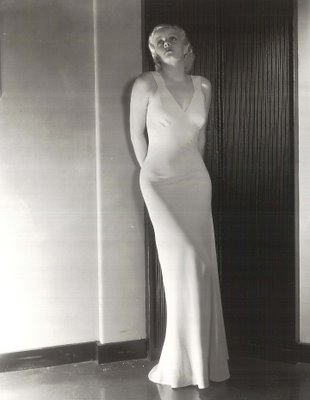

Jean Harlow in Platinum Blonde

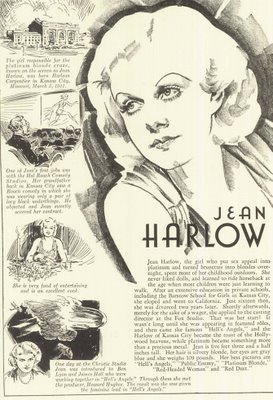

Jean's Picture Personalities Profile

MGM Publicity Portrait

With Wallace Beery in Dinner At Eight

Poster Art for The Girl From Missouri

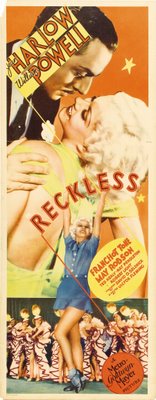

Reckless Insert

Jumbo Lobby Card from Libeled Lady

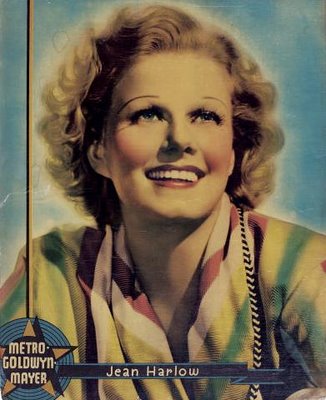

MGM Publicity Portrait

With William Powell in Reckless

With husband Harold Rosson, unrepentant gigolo step-father Marino Bello, and her mother.

Publicity for Harlow's new Brownette hair-style

Filming Saratoga with Lionel Barrymore, Walter Pidgeon, and director Jack Conway --- this may have been her last day on that set before she died.