Are Human Billboards Necessary?

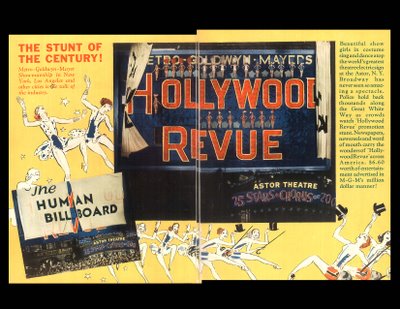

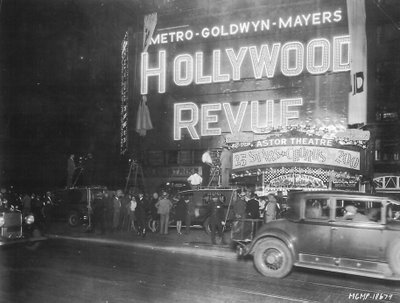

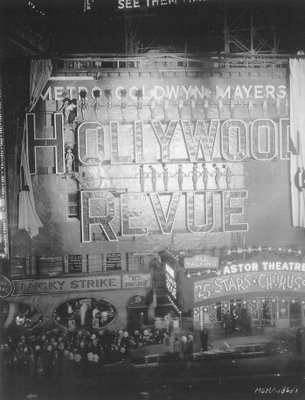

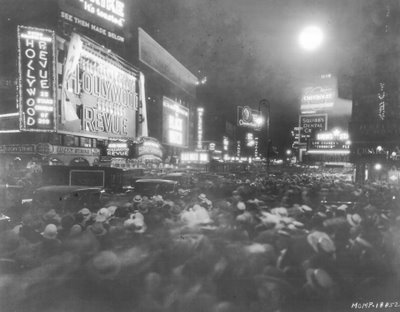

One can only assume that human life was cheap back in 1929, or maybe they saw the big Crash coming and just said to hell with it all, because suddenly, and for a brief shining moment, those Broadway marquees lit up with some of the most bizarre and extravagant bally stunts in the history of showmanship. Trade observers gave MGM credit for the first "Human Billboard" --- shown here at the Astor Theatre’s opening for The Hollywood Revue Of 1929. Those showgirls were obliged to pose for hours atop the individual letters of an enormous electric sign as it faced out onto a nightly mob of spectators. Never mind the risk of electrocution. What if they’d fallen? Those were narrow catwalks as you can see, and blinding searchlights wouldn’t enhance anyone’s equilibrium. What a way to make a living! The far shot gives you an idea of what Broadway had to offer on this particular evening --- click and enlarge to see those marquees for The Black Watch (John Ford’s first talking feature) and Lon Chaney’s final silent film, Thunder. There’s no record of any of those girls having tumbled from their perch, though we all would within a few weeks when Wall Street laid its egg.

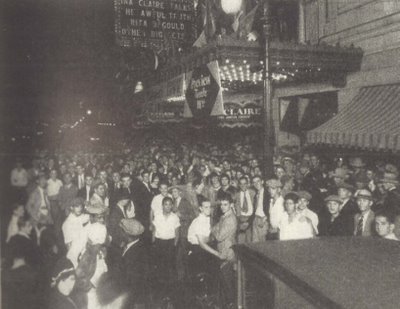

Others would emulate the Hollywood Revue stunt. Cleveland banned the human billboard when Metro tried to erect it there, citing city code violations. The local fire department was instructed to turn their hoses on the girls should they venture out onto the sign (poor things would have lighted up like Man-Made Monster’s Dan McCormick in that event!), while members of the constabulary stood by to arrest theatre staff members tempted to activate power. By the time the picture finally opened, controversy had stirred up sufficient press as to guarantee four thousand turnaways every day at the boxoffice. Metro’s mission was accomplished. A few weeks later, Fox went with a "Living Sign" for its Dallas, Texas engagement of The Cockeyed World. This time the billboard (shown above) was located two blocks from the Majestic Theatre where the show was playing. Buglers standing on the sign would sound off at regular intervals to be answered by more buglers stationed over the marquee back at the Majestic. Thirteen boys in Marine uniforms stood on the elevated billboard, accompanied by a thirty piece military band that played constantly. All this was to lead up to the midnight premiere of The Cockeyed World, but no one anticipated the teeming mass of humanity that would clog streets on opening night (that's them above). Lines for the show extended two blocks in as many directions. People were pushed against store windows and they broke. Streetcars were immobile. Women fainted. It was a great night at the movies in Dallas.

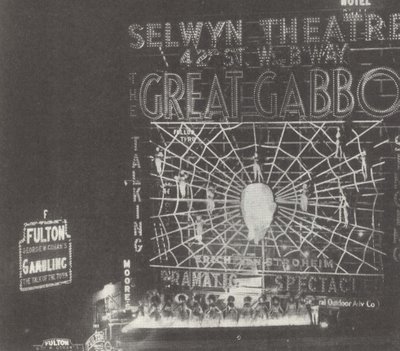

New York cops had a snoot-full of human billboards by the time The Great Gabbo blew into town in early October 1929, and now they were going to do something about it. A proposed court order alleged blockage of street traffic and needless congestion among pedestrians. Indeed, this bally was labeled "the first complete free show ever held on a Broadway roof to advertise a screen spectacle" --- a $12,000 structure featuring twenty showgirls dangling from an electrified spider’s web, while ten ballet dancers performed along the edge of the roof. As the still at left illustrates, all this took place 150 feet above street level. The presiding judge was persuaded by Gabbo producers to check out the billboard action for himself. Following a twenty-five minute view from an elevated vantage point opposite the sign, His Honor ruled in favor of the bally merchants and forbade further interference with their campaign, saying that "Broadway has become famous for its gargantuan display of mazda signs and that these electrical advertisements help to draw tourists to the thoroughfare from all parts of the world." Little did he realize that much of this was about to end, as that initial boom year for early talkies would soon be eclipsed by a stark downturn that would come with the Great Depression.