John Gilbert's Last Hurrah

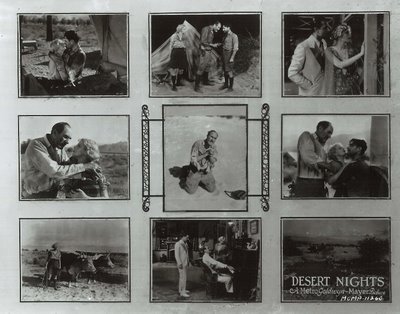

John Gilbert's Last HurrahRobert Osborne is a friend to all movie lovers. His intros on TCM are always engaging. I respect his knowledge, and admire his enthusiasm. This having been said, I would respectfully address a few of his comments that led into last month’s showing of Desert Nights (originally titled Thirst), John Gilbert’s last silent film. Bob related the story of how the movie opened and closed within a week at New York’s Capitol Theatre, which was Metro’s flagship house in Gotham. He said it flopped because everyone, by this time, preferred talking pictures. After seven days of play to empty seats, Desert Nights was yanked and declared a boxoffice failure. All of this came as a surprise to me, as I’d assumed that Gilbert’s troubles began with talkies. With the huge following he enjoyed in the wake of such hits as The Big Parade, Flesh and The Devil, and others, it seemed odd that his public would abandon the star in what seemed a tailor-made vehicle. Could this be another Gilbert myth? Perhaps not so pernicious as those never-say-die "white voice" slanders, but one that should be addressed and put straight. After all, hasn’t this fine actor’s reputation taken enough of a beating over the last seventy-five plus years?

First off, Desert Nights was no flop. It made money. Against a negative cost of $209,000, there were domestic rentals of $590,000, with foreign producing an additional $211,000. Worldwide rentals brought $801,000 for a final gain of $292,000. These profits exceeded those taken for a number of late silent Metros, including Lon Chaney’s Where East Is East and Thunder, Joan Crawford’s Our Modern Maidens, and Gilbert’s own Masks Of The Devil. One-week engagements were not unusual at the Capitol, or any other first-run house during the late twenties. That in itself did not indicate failure. Any notion that silent films were dead by March 9, 1929, when Desert Nights opened at the Capitol, are not supported by the facts. There were scarcely enough talking features by that time to supply even those comparatively few theatres wired for sound. Yes, the deluxe Broadway houses were equipped, but by no means finished with silent films in the late winter of 1929 --- and never mind those small-town venues across the country still using silents during the winter of 1930! When Desert Nights opened in March, Metro had only just released their first all-talking feature, The Broadway Melody. That had bowed the month before, and was a smash. MGM wisely delayed their debut talkie, and exploited that distinction with trade ads boasting of superior quality, ridiculing those companies who’d made precipitous leaps into sound. All of Metro’s popular attractions for the 1928-29 show season were otherwise silent. Most of these were available with music and effects, on film and disc, and a few had dialogue sequences. "Talking sensation" Alias Jimmy Valentine had come at the end of 1928, and was indeed a sensation, but the talking was minimal, and limited to a few odd sequences. The competition for Desert Nights during the week of March 9, 1929 included talkies from rival producers --- Coquette, Alibi, Weary River, The Canary Murder Case --- all had played, or were playing, around this time. Chances are, each of these pictures found a larger audience than Desert Nights --- such was the novelty of sound --- but the public was far from ready to abandon their silent favorites.

First off, Desert Nights was no flop. It made money. Against a negative cost of $209,000, there were domestic rentals of $590,000, with foreign producing an additional $211,000. Worldwide rentals brought $801,000 for a final gain of $292,000. These profits exceeded those taken for a number of late silent Metros, including Lon Chaney’s Where East Is East and Thunder, Joan Crawford’s Our Modern Maidens, and Gilbert’s own Masks Of The Devil. One-week engagements were not unusual at the Capitol, or any other first-run house during the late twenties. That in itself did not indicate failure. Any notion that silent films were dead by March 9, 1929, when Desert Nights opened at the Capitol, are not supported by the facts. There were scarcely enough talking features by that time to supply even those comparatively few theatres wired for sound. Yes, the deluxe Broadway houses were equipped, but by no means finished with silent films in the late winter of 1929 --- and never mind those small-town venues across the country still using silents during the winter of 1930! When Desert Nights opened in March, Metro had only just released their first all-talking feature, The Broadway Melody. That had bowed the month before, and was a smash. MGM wisely delayed their debut talkie, and exploited that distinction with trade ads boasting of superior quality, ridiculing those companies who’d made precipitous leaps into sound. All of Metro’s popular attractions for the 1928-29 show season were otherwise silent. Most of these were available with music and effects, on film and disc, and a few had dialogue sequences. "Talking sensation" Alias Jimmy Valentine had come at the end of 1928, and was indeed a sensation, but the talking was minimal, and limited to a few odd sequences. The competition for Desert Nights during the week of March 9, 1929 included talkies from rival producers --- Coquette, Alibi, Weary River, The Canary Murder Case --- all had played, or were playing, around this time. Chances are, each of these pictures found a larger audience than Desert Nights --- such was the novelty of sound --- but the public was far from ready to abandon their silent favorites.

In a New York Times article dated April 18, 1929, MGM production chief Irving Thalberg announced the "majority" of that company’s forthcoming releases would be available in silent versions, in the event of the failure of talking pictures to catch on. By this time, Metro had opened its second all-talkie, The Trial Of Mary Dugan, a March release, and was getting ready to unveil The Idle Rich and Madame X for later in April. Otherwise, it was silents as usual. Those music and effects were starting to come in for a drubbing from critics and exhibitors, however. Outspoken Pete Harrison, rebel publisher of Harrison’s Reports (Pete wouldn’t compromise his integrity by accepting ads from the film companies) said the theatres would be better off cobbling together their own scores from records rather than submit to lousy "canned" music provided with the features (those scores on disc increased film rentals as well). Another trade critic was disappointed when he went to the Capitol in October of 1929 to see Metro’s Speedway with William Haines, only to witness a live orchestra file out of the auditorium following a rousing overture, leaving the audience to enjoy Speedway with "electronic" accompaniment. This would have no doubt been the case with Desert Nights as well. Theatres viewed those recorded scores as a hedge against the expense of live musicians, and were determined to impose these upon the audience whether they were wanted or not.

In a New York Times article dated April 18, 1929, MGM production chief Irving Thalberg announced the "majority" of that company’s forthcoming releases would be available in silent versions, in the event of the failure of talking pictures to catch on. By this time, Metro had opened its second all-talkie, The Trial Of Mary Dugan, a March release, and was getting ready to unveil The Idle Rich and Madame X for later in April. Otherwise, it was silents as usual. Those music and effects were starting to come in for a drubbing from critics and exhibitors, however. Outspoken Pete Harrison, rebel publisher of Harrison’s Reports (Pete wouldn’t compromise his integrity by accepting ads from the film companies) said the theatres would be better off cobbling together their own scores from records rather than submit to lousy "canned" music provided with the features (those scores on disc increased film rentals as well). Another trade critic was disappointed when he went to the Capitol in October of 1929 to see Metro’s Speedway with William Haines, only to witness a live orchestra file out of the auditorium following a rousing overture, leaving the audience to enjoy Speedway with "electronic" accompaniment. This would have no doubt been the case with Desert Nights as well. Theatres viewed those recorded scores as a hedge against the expense of live musicians, and were determined to impose these upon the audience whether they were wanted or not.

My own small town didn’t have sound until December of 1929. That may seem unusual, over two years after The Jazz Singer, but the money involved in wiring even rural houses was astronomical in those days. You could expect to spend a minimum of five thousand, and that was enough to close down a lot of already struggling venues. Our own Orpheum Theatre (which became the Allen in 1941) was retrofitted, while the poverty-stricken Rose simply gave up and shuttered its doors. Throughout that year, we’d had a number of talking pictures --- silent versions of talking pictures. Desert Nights would have played with a local accompanist on an upright piano (one of my aunts sat at the keyboard in a similar small-town situation) --- music and effects scores were quite unknown to us. Ironic to note here that our Orpheum installed its sound equipment within a few weeks after MGM released its last silent feature, The Kiss.

I’ll be coming back to John Gilbert in future posts. In the meantime, I'd invite you to check out a brand new webpage (HERE) dedicated to Jack --- there’s nice images, interesting commentary, and even video clips. A real labor of love, and as we all know, Jack’s worth it!