skip to main |

skip to sidebar

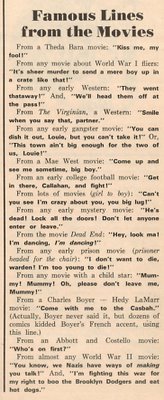

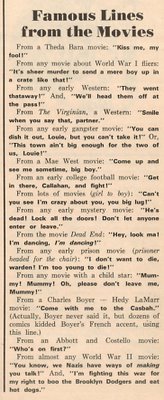

Old Movies In The ClassroomAnybody recognize this little magazine? We got them every week at school when I was in the eighth grade. This issue came across my iron maiden of a bubble-gum encrusted desk the week after my fourteenth birthday, and I’ve kept it close to my bosom ever since. It was the first time in my memory that movies were sanctified by the educational establishment. Oh yes, we’d watched Paramount’s Williamsburg – The Story Of A Patriot in the sixth grade, but this was reading of which my stern-visaged teacher/sadist would approve, and there was even a class discussion on the subject! Scholastic Scope was generally a crashing bore of a "news" weekly for adolescents --- often as not it would focus upon the Suez Canal, curing molasses, stuff like that. For the sake of context, I’ve included this Kellogg’s ad from the inside cover (what other possible reason could I have for featuring The Monkees at the Greenbriar?). I wonder if the winner of the contest got to be on that episode Lon Chaney, Jr. did? Anyway, The Story Of Movies is standard issue pabulum best left, I suspect, to the kids who were making their second or third go-round through the eighth grade. Just read these sample paragraphs under the "Standard Corny Cast" header and see what I mean. That’s pretty much the tenor of the article as a whole. So few books were available on the subject at that time --- sadly it was this sort of thing that people relied upon for their film history. We may have global warming now, but at least we’ve also got TCM. Recognize those "Famous Lines from the Movies"? Neither do I, but we took them for the truth then. By the way, Bill Everson once said, rightly I suspect, that the most oft-used line in westerns was not either of these, but the simple "Let’s get out of here!" which was spoken (eventually) in virtually every horse opera they ever made. Scholastic Scope also featured a helpful letters column in each issue, "What’s On Your Mind?" and in this particular number, there was a spirited debate as to a "disgusting" article which had been previously published on hippies. The writer suggested that he could not face a society that refused to embrace them (he should have been here this past weekend for our big annual music festival --- hippies were everywhere! --- possibly the same ones he was referring to). Another scribe lamented the criticism of boys with long hair. After all, he said, George Washington and Abe Lincoln had long hair (Abe did? I’d never noticed!). Anyway, having preserved the magazine for going on forty years, it seemed appropriate that I share the enrichment with Greenbriar readers, and I welcome comments from other Scholastic Scope readers and collectors.

Old Movies In The ClassroomAnybody recognize this little magazine? We got them every week at school when I was in the eighth grade. This issue came across my iron maiden of a bubble-gum encrusted desk the week after my fourteenth birthday, and I’ve kept it close to my bosom ever since. It was the first time in my memory that movies were sanctified by the educational establishment. Oh yes, we’d watched Paramount’s Williamsburg – The Story Of A Patriot in the sixth grade, but this was reading of which my stern-visaged teacher/sadist would approve, and there was even a class discussion on the subject! Scholastic Scope was generally a crashing bore of a "news" weekly for adolescents --- often as not it would focus upon the Suez Canal, curing molasses, stuff like that. For the sake of context, I’ve included this Kellogg’s ad from the inside cover (what other possible reason could I have for featuring The Monkees at the Greenbriar?). I wonder if the winner of the contest got to be on that episode Lon Chaney, Jr. did? Anyway, The Story Of Movies is standard issue pabulum best left, I suspect, to the kids who were making their second or third go-round through the eighth grade. Just read these sample paragraphs under the "Standard Corny Cast" header and see what I mean. That’s pretty much the tenor of the article as a whole. So few books were available on the subject at that time --- sadly it was this sort of thing that people relied upon for their film history. We may have global warming now, but at least we’ve also got TCM. Recognize those "Famous Lines from the Movies"? Neither do I, but we took them for the truth then. By the way, Bill Everson once said, rightly I suspect, that the most oft-used line in westerns was not either of these, but the simple "Let’s get out of here!" which was spoken (eventually) in virtually every horse opera they ever made. Scholastic Scope also featured a helpful letters column in each issue, "What’s On Your Mind?" and in this particular number, there was a spirited debate as to a "disgusting" article which had been previously published on hippies. The writer suggested that he could not face a society that refused to embrace them (he should have been here this past weekend for our big annual music festival --- hippies were everywhere! --- possibly the same ones he was referring to). Another scribe lamented the criticism of boys with long hair. After all, he said, George Washington and Abe Lincoln had long hair (Abe did? I’d never noticed!). Anyway, having preserved the magazine for going on forty years, it seemed appropriate that I share the enrichment with Greenbriar readers, and I welcome comments from other Scholastic Scope readers and collectors.

Selling, Chasing, and Collecting The MummyWhen it comes to the subject of Universal horror films, critical objectivity is quite beyond me. Sentiment and nostalgia are guiding principles in any discussion I may have regarding these pictures. Whether good or bad by anyone else’s measure is quite beside the point. My expectation at age fifty-two is that I will spend at least a few moments of my dying day, whenever that happens to be, ruminating over happy boyhood hours when I first came upon Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Mummy. A casual search of the Internet will confirm that I'm not alone in my enthusiasm. A surprising number among my generation seem to have experienced similar reaction after these began showing up on television in 1957. How one package of features, the content of which even at that time was between eleven and twenty six years old, could have so completely captured the imagination of fifties and sixties youth is a continuing paradox. There’s certainly been nothing like it since. Part of this was sheer difficulty in seeing the things. Most TV markets carried the "Shock" group (a syndicated umbrella covering most of the Universal horrors), but you were lucky if your station ran them twice in a year. A few miserly channels in our area went two years or more between broadcasts, and you had to rely upon Famous Monsters Of Filmland magazine to refresh memories of beloved icons such as Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Lon Chaney, and the rest. Some of us can recite day and date of each encounter with Bride Of Frankenstein, The Black Cat, and other classics. They were ones we saw when it was possible to be truly impressed by a movie, long before regrettable onset of maturity when one applies critical standards, and nothing’s capable of really exciting you anymore. I saw it coming at fourteen, and recognizing signs even then. Sneering at The Green Slime, walking out on Destroy All Monsters, even turning my back on a Hammer film, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed. Childhood’s warm embrace of all things horrific would not last beyond 1968 for me, and yet, the essentials remained dear, and of all these, perhaps The Mummy remains most cherished.

Selling, Chasing, and Collecting The MummyWhen it comes to the subject of Universal horror films, critical objectivity is quite beyond me. Sentiment and nostalgia are guiding principles in any discussion I may have regarding these pictures. Whether good or bad by anyone else’s measure is quite beside the point. My expectation at age fifty-two is that I will spend at least a few moments of my dying day, whenever that happens to be, ruminating over happy boyhood hours when I first came upon Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Mummy. A casual search of the Internet will confirm that I'm not alone in my enthusiasm. A surprising number among my generation seem to have experienced similar reaction after these began showing up on television in 1957. How one package of features, the content of which even at that time was between eleven and twenty six years old, could have so completely captured the imagination of fifties and sixties youth is a continuing paradox. There’s certainly been nothing like it since. Part of this was sheer difficulty in seeing the things. Most TV markets carried the "Shock" group (a syndicated umbrella covering most of the Universal horrors), but you were lucky if your station ran them twice in a year. A few miserly channels in our area went two years or more between broadcasts, and you had to rely upon Famous Monsters Of Filmland magazine to refresh memories of beloved icons such as Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Lon Chaney, and the rest. Some of us can recite day and date of each encounter with Bride Of Frankenstein, The Black Cat, and other classics. They were ones we saw when it was possible to be truly impressed by a movie, long before regrettable onset of maturity when one applies critical standards, and nothing’s capable of really exciting you anymore. I saw it coming at fourteen, and recognizing signs even then. Sneering at The Green Slime, walking out on Destroy All Monsters, even turning my back on a Hammer film, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed. Childhood’s warm embrace of all things horrific would not last beyond 1968 for me, and yet, the essentials remained dear, and of all these, perhaps The Mummy remains most cherished.

The chase after The Mummy was launched with 16mm collecting. This was long before videocassettes. Why wait for the thing to show up on television when you can score your own print, preferably one of those rare originals? Now an original was that elusive specimen generated through the legitimate auspices of the current copyright owner. In this case, it was Screen Gems distribution, the syndication arm of Columbia. They had leased the horrors from Universal and supplied individual TV stations with 16mm prints. Your hopes of getting one of those were pretty nil. A few got pilfered out of storage rooms and distribution terminals, but you didn't want to get your hands too warm handling contraband like this. Better to settle for a "dupe" (a bootlegged copy made from an original) or an older legit print that had cooled off by virtue of its having been with the same collector for a number of years. This was how I finally got my bonifide 1957 original of The Mummy. Collecting comrade Robert Cline and I ventured forth once again into that bizarre netherworld of obsessive film hoarders who’d long since retreated from society as we know to a place largely unknown among normal, functioning adults. Our host on this occasion was the male counterpart of Miss Havisham, his darkened home filled with hundreds of loudly ticking antique clocks. He must have spent all day every day winding the things. I don’t know how he slept among all those timepieces. Actually, I don’t think he slept at all. One or two of his cats resided in the refrigerator, as I recall. Their means of ingress and egress were not explained to us. His print of The Mummy resided in yet another of those suffocating basements so beloved by collectors. You couldn’t read the titles on the reels without a flashlight, and naturally, his had dead batteries. You see, Vitus, the batteries are dead. Even the batteries are dead. So, was it worth all this? Emphatically yes! Big yes! That liquid, silvery Kodak safety positive looked like a vintage woodcut. I could almost read those hieroglyphics right along with Bramwell Fletcher during that opening sequence. Would I go through something like this again? No. Decidedly no. DVD’s have made my collecting life simpler. But nice as the DVD of The Mummy looks, it’s still not quite the same experience as watching that 16mm beauty I once owned.

The Mummy pursuit wasn’t confined to 16mm. There were also original posters, at least those few that actually survived. A friend of mine found out about one of them by sheer happenstance. Seems there was a handyman who’d done yard work for an elderly woman with whom he’d become friendly after several seasons of lawn and gutter work. One day over a tall glass of Lipton’s, she casually mentioned an old movie poster which had been given her as a wee child by a kindly old exhibitor way back in 1933. Would he care to see it? Not wanting to appear rude, the tradesman feigned interest as the old lady unfurled the folded original one-sheet for The Mummy she’d had for the last sixty years (here’s what one of those looks like). His reaction was calm. He neither tried to barter for it, nor dispatched her with a claw hammer to steal it. Instead, he went about his business, and only mentioned it to my friend’s father weeks later because he knew the man had a son who was into movie posters. My friend (who shall remain nameless, as he wishes to avoid being tortured into revealing the woman’s name and address) immediately commissioned said handyman to return to the woman with an offer. This time her radar was up. It wasn’t just no, but hell no! She’d been pestered by these would-be purchasers before, and she wasn’t about to be done out of her priceless Mummy poster by any guy that raked leaves for a living! Needless to say, the deal went cold. That was over ten years ago. My friend told me yesterday it’s still cold. In fact, for all he knows, that old lady might be cold as well. It’s a cinch you won’t get any updates on her from that handyman. He’s clipped his last hedge at her place. Meanwhile, there’s a one-sheet for The Mummy unaccounted for. But please, you rabid poster collectors. Don’t bother torturing me for her name and address. I asked my friend never to reveal those --- for my own protection.

Were they still with us, you could ask David Manners and Zita Johann about The Mummy chase. Both of them lived long enough to experience it, though I’m not so sure they enjoyed the experience. After all, how do you evade an army of fans when you’re pushing ninety and all of your pursuers are hale and hearty mid-lifers (and even the most fragile of us monster acolytes are capable are breaking into a dead run at the sight of a surviving Universal horror star)? Boris Karloff and Edward Van Sloan were the lucky ones. They died before us monster kids grew up. Neither of them had to face the prospect of anxious would-be interviewers banging on their nursing home door. Poor Dave and Zita made it into the 1990's. Manners lived to a ripe ninety-seven. He got to where he was telling fans he’d rather die than submit to another interview. He just wanted to eat pancakes in the dining room with the rest of the seniors. Telling yet another horror fan what it was like working with Bela Lugosi was worse than a rectal exam for him. Not that I’m setting myself above his inquisitors, mind you. I once wrote Mr. Manners a fan letter, back in 1969, and wouldn’t you know it? He didn’t want to talk to me either. Zita was more receptive. In fact, she even supplied the forward for a really neat book about the production history of The Mummy (written by that ace researcher Greg Mank). Zita dished all sorts of inside scoop on that long ago month she spent in the company of Boris Karloff (a true gentleman) and director Karl Freund (total bastard). She was living in Nyack, N.Y., her serene retirement interrupted only by a gentle tapping, someone rapping, at her chamber door. Sure enough, another fan with questions about The Mummy. Zita almost made it to ninety. I suspect a lot of those Mummy-philes would have gladly followed her over to the other side, if only such a thing weren’t so --- permanent. Hey --- could be worth it at that --- just imagine, a full cast and crew Mummy reunion! Can Heaven really hold the promise of such delights? Let's hope so!

And now --- these pictures. I know I harp a lot on going back in time, but honestly, wouldn’t you just give anything to have walked down good old Main Street, past the starving depression folk selling apples, and encounter theatre-front displays like these? How about facing that store window with the live Mummy and "sleeping woman" tableau (those spectators look fascinated)? And that girl who "comes to life" in the lobby? Did she lie there all day? Wonder what they paid her. Roving mummies in the street --- mummies giving out dollar bills (Wow! Bet those mummies were more sought after than an octogenarian David Manners!). Over in England, they had two dozen guys with sandwich boards taking to the sidewalks, in addition to the street mummies. Those UK showmen sure knew their onions. Closer to home, that marquee that reads, "The Mummy – It Comes To Life" is Charlotte NC’s own Broadway Theatre, now long leveled and gone. To think, I could have walked to that show from where I live. Only ninety miles. Yeah … easy walk.

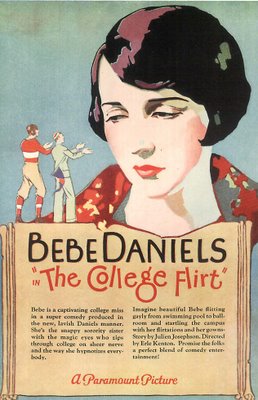

Monday Glamour Starter --- Bebe Daniels

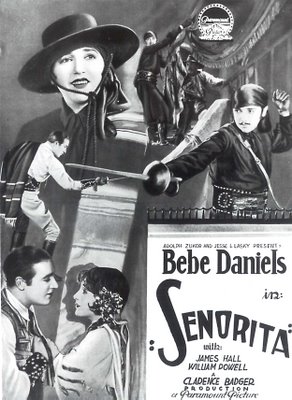

Monday Glamour Starter --- Bebe Daniels It wasn’t so extraordinary in 1915 for fourteen-year old girls to play leading lady opposite silent comedians. It was extraordinary that one of those adolescents, already a veteran of stage and screen when she signed on to play "the girl" in Harold Lloyd’s "Lonesome Luke" one-reelers, would go on to enjoy a career that lasted into the sixties, one which would successfully embrace virtually all twentieth-century media. Why someone hasn’t written a major biography of Bebe Daniels is an ongoing paradox to me. I should think that at the very least, some woman’s studies professor would get hep to the fact that here was a feminine dynamo who masterminded a series of amazing careers --- each of them enormously profitable --- and none of them possible had it not been for Bebe’s creative guiding hand. If the movies had a Renaissance woman, she was it. One of the big reasons we don’t know her better is the fact that she and husband Ben Lyon took the show across the pond in the mid-thirties, and the phenomenal popularity she garnered over there was all but unknown stateside. By the time she died in 1971, we’d forgotten all about Bebe Daniels. Indeed, she was little more than an obscure name who’d once shared the bill with Rudolph Valentino and Harold Lloyd (that’s her with Rudy in 1924’s Monsieur Beaucaire). We were just too provincial to realize how much territory her stardom took in. To this day, we still don’t get it.

It wasn’t so extraordinary in 1915 for fourteen-year old girls to play leading lady opposite silent comedians. It was extraordinary that one of those adolescents, already a veteran of stage and screen when she signed on to play "the girl" in Harold Lloyd’s "Lonesome Luke" one-reelers, would go on to enjoy a career that lasted into the sixties, one which would successfully embrace virtually all twentieth-century media. Why someone hasn’t written a major biography of Bebe Daniels is an ongoing paradox to me. I should think that at the very least, some woman’s studies professor would get hep to the fact that here was a feminine dynamo who masterminded a series of amazing careers --- each of them enormously profitable --- and none of them possible had it not been for Bebe’s creative guiding hand. If the movies had a Renaissance woman, she was it. One of the big reasons we don’t know her better is the fact that she and husband Ben Lyon took the show across the pond in the mid-thirties, and the phenomenal popularity she garnered over there was all but unknown stateside. By the time she died in 1971, we’d forgotten all about Bebe Daniels. Indeed, she was little more than an obscure name who’d once shared the bill with Rudolph Valentino and Harold Lloyd (that’s her with Rudy in 1924’s Monsieur Beaucaire). We were just too provincial to realize how much territory her stardom took in. To this day, we still don’t get it.

That neat set of DVD’s called More Treasures From The American Film Archives contains a hitherto lost subject from 1910 called The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz. They say it’s the first screen adaptation of the L. Frank Baum stories, and the nine-year old kid playing Dorothy is Bebe Daniels. That’s her with the Scarecrow and others in the fuzzy shot, and get this, she’d already trod the boards five years when she made it. Convent school was a drag because the other girls with their dollies were unfamiliar with Shakespearean passages, which Bebe could by now quote. Precocious was hardly an adequate word to describe the nubile teen who stormed the Hal Roach lot and defied the studio’s preference for a blonde ingenue to act as foil for a twenty-two year old Harold Lloyd. Brunette Bebe got the job through sheer force of personality and made a staggering 144 short comedies with the comedian before decamping in 1919 to go work for Cecil B. DeMille. In the meantime, she and Harold had a thing going which might have led to the alter were it not for her ambition and his ambivalence. Career minded Harold met his match in Bebe. He liked his women passive. She was anything but. Chances are he loved her, because he wore a ring she’d given him until the day he died (Harold and Bebe passed within eight days of the other in ’71). DeMille and Jesse Lasky had noted her popularity with Harold and tried to poach her away from Roach, a major breach of protocol in those days. When her contract was finally up, Bebe headed over to Paramount and $1000 a week, up from the $100 she was pulling down at Hal’s "Lot-A-Fun." Shrewd tactic, for this was where the serious Stardust would gather on her.

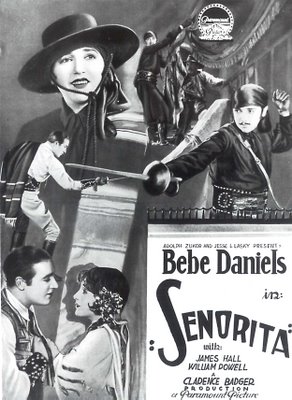

Crazy publicity stunts were the order of the day in the twenties, and Bebe pulled off a doozy when she got herself arrested for speeding (72 MPH in a 50 zone) and was sentenced to ten days in a podunk jail within hailing distance of Hollywood and its non-stop press brigade. No sooner was she ensconced in the hoosegow than a procession of celeb friends arrived to relieve her anguish. A Persian rug and ivory bedroom set adorned her cell, and the guestbook she maintained during the incarceration eventually netted 792 signatures (bet that would be quite a collector’s item today!). Abe Lyman and His Orchestra serenaded her from outside the barred window. The whole silly business culminated with Bebe’s next vehicle following her release, The Speed Girl. That one’s lost, as are virtually all of her Paramount features. These images and trade ads can only suggest what all those pictures might have been like. At least one of them, Senorita, does survive, but good luck seeing it, as it’s only been unspooled at one US silent movie gathering I’m aware of. As you can see, Bebe plays a kind of female Zorro in it. She was quite the athlete on screen, forever running, swimming, riding --- in a seemingly endless series of college comedies, romantic farces, costume capers --- whatever sold. She was also going in at night and helping edit the movies, plus writing, then producing. Eventually, she had her own unit at Paramount, and near complete autonomy to do the pictures as she saw fit. Bebe had a way of lucking into headlines that earned her the (benign) nickname of "The Good Little Bad Girl." On one occasion, her jewelry was stolen during a stopover in Chicago. Mob capo Al Capone got wind of it and sent out the word that Bebe’s baubles had better be returned --- or else. Legend has it that Big Al himself delivered the ice next day. Talk about landing in a field of clover! Was it any wonder that Bebe was the hottest Mama in movies?

Talkies dealt a cruel blow when Paramount inexplicably refused to give Bebe a voice test. Part of that was anxiety over sound prospects for silent stars, and the studio’s belief that stage players would naturally supplant former idols, with the happy outcome of paying unknown legit players far less than established names like Bebe Daniels were getting. Efforts to get before a microphone were rebuffed, so Bebe bought out her remaining contract, then headed for RKO, where she scored a triumph as the singing lead in Rio Rita, a smash hit (hey, it out-grossed King Kong!) which led to a brace of musicals culminating with the one she’s best remembered for, 42nd Street (1932). Bebe was a stirring presence in a number of pre-code favorites --- some of them illustrated here --- The Maltese Falcon with Ricardo Cortez, Reaching For The Moon opposite Doug Fairbanks, Sr., and as romantic vis-à-vis to John Barrymore in a great one, Counselor-At-Law. Despite good work in these, her leading status had diminished, and the move to England in 1935 seemed a good opportunity to regroup. That it would lead to an entirely new, and fantastically successful second career, could not have been anticipated.

Any performer who would broadcast through a London air raid was some kind of alright as far as the British public was concerned, and it was this sort of courage under fire that made Bebe and husband Ben Lyon (married since 1930) national institutions around the U.K. They started in music halls, where man-and-wife variety acts enjoyed great popularity during the late thirties, but it was radio that really put them over. The real-life bickering (but ultimately devoted) show-biz couple formula was still fairly fresh at that time, and Hi, Gang! was a wartime ritual for listeners throughout the isles. The Lyons would even take a leaf from Ozzie and Harriet Nelson’s book when they converted the series into a family sitcom shortly after the war. Real-life son and daughter Barbara and Richard teamed with their parents for Life With The Lyons, and there would be two features (produced by Hammer Films!) and a television series spun off from there (here they are on the set). This was the first program of its kind in England, and Bebe Daniels co-wrote all the episodes. She maintained a vault of jokes and comic situations accumulated over her forty plus years in the business. Harry Truman awarded Bebe the Medal Of Freedom for wartime work on behalf of our allies. She was the first woman to come ashore at Normandy after the invasion. It’s really a shame Bebe Daniels isn’t better known today. Her death in 1971 came just short of what might have been a major rediscovery by writers and historians, and a book-length investigation of her life and accomplishments is certainly a thing now long overdue.

Our thanks to poster dealer and collector Bruce Hershenson for his kind permission to use the very attractive one-sheet image of Bebe Daniels in Rio Rita, which we found in Bruce’s excellent compilation, Musical Movie Posters (you can order that HERE).

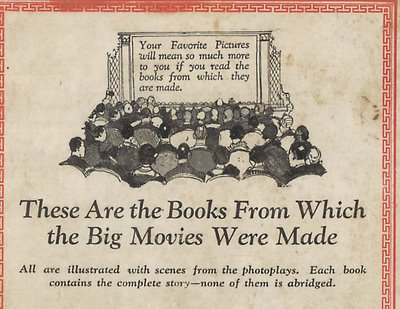

Photoplay Editions On ParadeAmong book/movie tie-in collectibles, the Photoplay editions are sought after primarily for their attractive dust jackets, and the photo plates generally featured with the text. They began to appear in 1913, and were at first designed to promote and accompany the ongoing serial adventures of stars such as Pearl White and Ruth Roland. They later became novelizations of feature stories and screenplays. I found one for Beyond The Rocks at a local sale for the public library, and it had a neat image of Gloria Swanson on the still-intact dust cover. The rarest ones are for things like Dracula and King Kong --- no surprise there. Photoplay editions died out by the mid-thirties, but books based on movies continued right along until paperbacks became dominant after the war. The ones shown here were issued in tandem with the release of The Freshman and Speedy, and these colorful editions must have been quite a lure for Harold Lloyd fans in the book stalls. The photo from Speedy was included as an illustration plate in the novel --- note the caption and credit. Though Lloyd was high on Photoplay editions, Charlie Chaplin apparently was not, as there are no Photoplays extant on Chaplin’s features. These little books can still be had at a right price, but beware those without dust-jackets. Condition’s a factor too. If you’re going to bid on one, make sure all the illustrations are intact. Otherwise, these are fun books, and nice souvenirs of a tie-in device that has largely disappeared.

Photoplay Editions On ParadeAmong book/movie tie-in collectibles, the Photoplay editions are sought after primarily for their attractive dust jackets, and the photo plates generally featured with the text. They began to appear in 1913, and were at first designed to promote and accompany the ongoing serial adventures of stars such as Pearl White and Ruth Roland. They later became novelizations of feature stories and screenplays. I found one for Beyond The Rocks at a local sale for the public library, and it had a neat image of Gloria Swanson on the still-intact dust cover. The rarest ones are for things like Dracula and King Kong --- no surprise there. Photoplay editions died out by the mid-thirties, but books based on movies continued right along until paperbacks became dominant after the war. The ones shown here were issued in tandem with the release of The Freshman and Speedy, and these colorful editions must have been quite a lure for Harold Lloyd fans in the book stalls. The photo from Speedy was included as an illustration plate in the novel --- note the caption and credit. Though Lloyd was high on Photoplay editions, Charlie Chaplin apparently was not, as there are no Photoplays extant on Chaplin’s features. These little books can still be had at a right price, but beware those without dust-jackets. Condition’s a factor too. If you’re going to bid on one, make sure all the illustrations are intact. Otherwise, these are fun books, and nice souvenirs of a tie-in device that has largely disappeared.

Bill Powell's Fishing ExpeditionIt’s August of 1936, and we’re on location with director Jack Conway and star William Powell as they prepare to shoot Bill’s comedic fishing foray for that MGM howl-fest, Libelled Lady, also featuring Jean Harlow, Myrna Loy, and Spencer Tracy. A lot of crew guys are getting soaked, as you can see, and judging by the duration of that very funny sequence in the finished movie, they must have spent several days, if not the week, treading water to get the whole thing down on finished film. Trouper Bill’s taking it all with a good-natured smile, but wouldn’t he have been surprised to learn that we’d still be watching, and enjoying, Libelled Lady some seventy years later. Anyone know just where this outdoor stuff was shot?

Bill Powell's Fishing ExpeditionIt’s August of 1936, and we’re on location with director Jack Conway and star William Powell as they prepare to shoot Bill’s comedic fishing foray for that MGM howl-fest, Libelled Lady, also featuring Jean Harlow, Myrna Loy, and Spencer Tracy. A lot of crew guys are getting soaked, as you can see, and judging by the duration of that very funny sequence in the finished movie, they must have spent several days, if not the week, treading water to get the whole thing down on finished film. Trouper Bill’s taking it all with a good-natured smile, but wouldn’t he have been surprised to learn that we’d still be watching, and enjoying, Libelled Lady some seventy years later. Anyone know just where this outdoor stuff was shot?

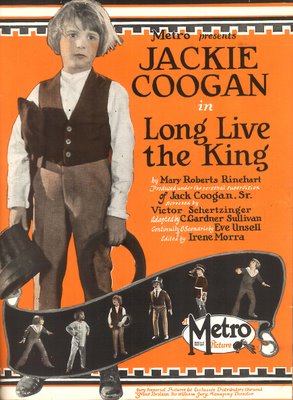

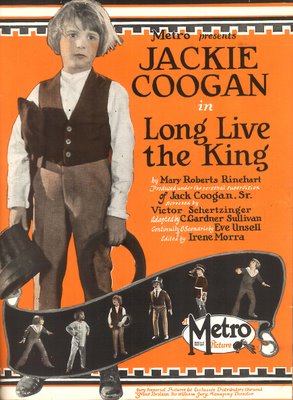

Child Star Supreme --- Jackie CooganJackie Coogan is the only motion picture star I’m aware of who actively participated in a lynching. Perhaps there were others, but after all, this is not something you would find in official studio bios. Jackie was also the first international child phenomenon. You might even go beyond that and call him a religious figure. No one of our generation can possibly comprehend the level of stardom this kid enjoyed (and by all accounts, he really did enjoy it, even if the whole thing did come crashing down later). Jackie rang the opening bell for an age of child worship which would utterly transform the way in which society viewed its young. The fact he was idolized and pampered on the public stage while being systematically robbed and exploited at home was an irony that would galvanize a nation when those shocking headlines broke on April 11, 1938. In his heyday, Jackie was an adorable puppet for a set of vaudeville parents from Hell who’d somehow lucked into siring the most remarkable money machine the screen had known up to that time. The mother was called Lillian. She silenced a crowded banquet hall once when she referred to herself as "the goose that laid the golden egg." Some joke, huh? The father was Jack, Sr. He was a vaude vet gone to seed with a line of cruel practical jokes and the usual baggage that went with the biz --- liquor, gambling, reckless spending. With role models like these, what chance did Jackie ever have?

Child Star Supreme --- Jackie CooganJackie Coogan is the only motion picture star I’m aware of who actively participated in a lynching. Perhaps there were others, but after all, this is not something you would find in official studio bios. Jackie was also the first international child phenomenon. You might even go beyond that and call him a religious figure. No one of our generation can possibly comprehend the level of stardom this kid enjoyed (and by all accounts, he really did enjoy it, even if the whole thing did come crashing down later). Jackie rang the opening bell for an age of child worship which would utterly transform the way in which society viewed its young. The fact he was idolized and pampered on the public stage while being systematically robbed and exploited at home was an irony that would galvanize a nation when those shocking headlines broke on April 11, 1938. In his heyday, Jackie was an adorable puppet for a set of vaudeville parents from Hell who’d somehow lucked into siring the most remarkable money machine the screen had known up to that time. The mother was called Lillian. She silenced a crowded banquet hall once when she referred to herself as "the goose that laid the golden egg." Some joke, huh? The father was Jack, Sr. He was a vaude vet gone to seed with a line of cruel practical jokes and the usual baggage that went with the biz --- liquor, gambling, reckless spending. With role models like these, what chance did Jackie ever have?

Charlie Chaplin should have gotten a piece of the action, because he sure enough invented Jackie Coogan. In fact, it was Charlie’s Kid character that J.C. would continue to play, with only slight variation, for the rest of his career as a child star, even down to the costume. It’s a testament to Chaplin’s genius that the public would be willing to continue buying what was essentially his product so long after he stopped personally manufacturing it. Opportunist producers like Sol Lesser (he of the much later Tarzan pics for RKO) snapped up Jackie as soon as The Kid made the six-year old a worldwide sensation, and from there it was just a matter of recycling all the stuff that had worked in the Chaplin show, namely comedy, pathos, beleaguered child shtick --- whatever would keep the train on track. Some say Jackie represented the plight of war orphans. Others put forth a theory that merchandising, at least as it’s directed toward kids, was born with Jackie Coogan. Still more will say that when we embraced Jackie, we finally shuffled off that quaint Victorian concept about children being seen and not heard, etc. If you want to throw in notions about Jackie’s popularity being borne of increased leisure time resulting from the machine age and the availability of labor saving devices, you can go ahead and apply for an Ivy League Master’s program and eventually start your own Jackie Coogan Cultural Studies Department at Yale!

They found out quick you couldn’t take Jackie out in public. Lillian carried him along to a department store two-for-one and wound up with three thousand crazed shoppers swarming over the hapless child. It took police intervention to extricate them. By the time he signed with Metro in 1923, Jackie (or I should say his parents) were scoring $1.35 million a year. A lot of that came from product endorsements. In those days, they had Jackie toys and dolls up the wazoo. His cherubic face graced song sheet covers you could look at while banging out I’m Just A Lonely Little Kid on the upright piano. Jackie hung out with Doug Fairbanks, Rudolph Valentino, Babe Ruth --- all the biggest names. They were thrilled to be seen with him. Dad kept ruder company, and it was these that really influenced the boy. Jack, Sr. brought his son along for drinking bouts with Bill Fields, Ben Turpin, Roscoe Arbuckle --- nobody’s idea of fit company for a growing lad. Wicked Uncle Bill gave Jackie a crash course in the use of profanities, which the child would later apply in more polite conversation, causing no end of embarrassment for studio publicists. The lowdown parental house of cards finally collapsed when Lillian took up furtive canoodling with one Arthur Bernstein, who’d lately become business manager for the Jackie Coogan Corporation, itself little more than a clearing house to siphon off Jackie’s earnings for the parent's own use and gratification. While these bejeweled parasites drove fancy roadsters and hovered over roulette wheels, Jackie worked twelve-hour days, six-day weeks. Even after the movie thing faded, they had him hustling from a music hall stage over in England, where big money could still be had for star names, even those on the wane. The awkward age dealt a growth spurt that transformed Jackie into a Tom Sawyer that 1930 audiences barely recognized, and from there it would just be a matter of time before he would he finally realize what Mom and Dad had done to him.

Jackie’s parents knew from nothing about a college education, but it seemed a reasonably good way to harness the young man’s excess energies, so it was off to Santa Clara University, where the most alarming episode of Jackie’s life, and the one most completely hidden from his public, would take place. The year was 1933, and carefree Jackie was majoring in alcoholic studies and advanced cheerleading when he made friends with a popular local youth from a prominent Santa Clara family, Brooke Hart. During this era of sensational kidnappings, the public’s outrage was daily renewed by horrific incidents of abduction and murder (the Lindbergh case still fresh in collective memories). It was against this background that Brooke Hart was taken by a pair of local nincompoops, unceremoniously beaten to death and thrown into a river before a ransom could be collected, a botched job down the line, but one which awakened mob frenzy that culminated in both men being taken out of their cells and hanged in the public square before a cheering crowd of 10,000 Santa Clara witnesses. Although he wasn’t photographed at the scene, there were those who recognized Jackie preparing the noose and lending an enthusiastic assist to the deadly enterprise. Although Jackie would never mention it during his lifetime (no one was ever prosecuted in connection with the incident), the truth of his involvement would finally reveal itself in an excellent "true crime" book, Swift Justice, which was published in 1992. Jackie’s own situation went from bad to worse when his father crashed the brand new Ford coupe he’d just given Jackie for his twenty-first birthday, killing himself and three passengers. The only survivor of the horrific 1935 crash was Jackie. His next crash would come in 1938, and that’s when he finally sued his mother and now stepfather --- only to find they’d converted all his fortune and left him stony. A bitter Coogan later told interviewers he’d netted only $35,000 from the ordeal, out of the four million he’d earned as a child actor.

The single most enduring image of Jackie Coogan is the one he shared with Charlie Chaplin in The Kid. When Jackie went broke (the first of many such occasions), a sympathetic Chaplin spotted him ten G’s. Who says Charlie was stingy? That’s Jackie and his expensively tailored parents on the Metro lot --- watch-chain, spats, and fur courtesy the kid. Jackie wasn’t the title character in The Rag Man, but it seems he was always dressed in them. Audiences preferred him in ragamuffin attire and circumstances for most of his shows, but Metro tried something different for two shown here in trade ads --- Long Live The King and Little Robinson Crusoe. Both are out of circulation today, though it’s rumored Warners preserved some Metro Coogans, but won't run them because of rights issues. Part of Jackie’s settlement with the crook parents gave him rights to negatives of these features. Is it possible his estate owns them yet (he died in 1984)? Maybe a meeting of minds between Warners and the Coogan family can put some of Jackie’s starring vehicles back in circulation. My online copyright search couldn’t turn up any reference to them. Orphan movies, just like most of Jackie’s roles. This exhibitor ad with Jackie in military garb came toward the end of his starring career. The Bugle Call and Buttons were both profitable, but talkies and adolescence, not to mention Louis Mayer’s antipathy, combined to scuttle him. Tom Sawyer at Paramount was a brand new Jackie, seen here with Mitzi Green and Junior Durkin, a close friend who would later die in that infamous wreck that killed Jack, Sr. Newlyweds Betty Grable and Jackie Coogan are whooping it up in College Swing. When someone asked her years later about the failed marriage to Jackie, Betty paid moving tribute when she said, "Listen honey, Coogan taught me more tricks than a whore learns in a whorehouse." You go, Jack!! Finally we have a couple of down-on-their-luck kid stars teaming up to pay the rent --- the Jackies Coogan and Cooper in Kilroy Was Here, a flea-bitten Monogram special they did in 1947. Coogan would have a comeback of sorts as Uncle Fester in The Addam’s Family, but the once beautiful boy hated playing it grotesque. The stardom of his youth was now so remote, he couldn’t even persuade his grown daughter of how big he’d once been. What a life this guy had. By far the best bio is the one by Diana Serra Cary (a former child star herself) called Jackie Coogan --- The World’s Boy King, and it’s a terrific read.

It's Always Fair Weather

It’s Always Fair Weather is best enjoyed by middle-aged viewers who can identify with the malaise and disillusionment of the three principal characters, and since this has never been the primary demographic among moviegoers, it was probably inevitable this movie would fail. That plus the fact MGM musicals were beginning to pall at the wickets --- for every Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, there were six like Brigadoon, Hit The Deck, Athena, Deep In My Heart --- such a reservoir of red ink raises the question as to why they kept doing them at all. Here’s a surprising factoid for Gene Kelly’s fans --- every single feature he did for Metro after Singin’ In The Rain lost money. A few of the specific losses, in millions --- Brigadoon ($1.4) --- It’s Always Fair Weather ($1.5) --- Invitation To The Dance ($2.4) --- and Les Girls ($1.5). You begin to wonder how he even got a pass to drive on the lot. I’m awfully glad he did though, because It’s Always Fair Weather is one terrific MGM musical, the Little Big Horn of valiant song and dancers staging one more big show as their fickle audience retreats home to their televisions and rock ‘n roll platters. Its domestic rental was a woeful $1.4 million. Within a year, a black and white piece of cheese called Love Me Tender would take home $4.2. Times and tastes, they were a-changin’.

A lot of people like this musical because of its "dark" aspects --- that’s probably gotten it through a lot of revival house and university doors where it might otherwise have been snubbed. It’s mostly Dan Dailey’s character hauling that baggage, and all because he’s been "reduced" to designing animated commercials for television! Now maybe I’m misinformed as to the definition of success on Madison Avenue in the fifties, but I would think any guy who’d developed a nationwide ad campaign, in any media, would have to be considered an up-and-comer, if not an already-got-there. Greg Peck’s Man In The Grey Flannel Suit could have fixed up that shabby old house and gotten Jennifer Jones off his back had he pulled off such a coup. I suspect poor Dan’s despair lay in the fact that he’d whored himself out to television, and that in itself was enough to bring on (well deserved) alcoholism and ulcers for any character in an MGM feature. Every depiction of TV here is a withering putdown, whether it be Dolores Gray’s hostess gorgon, or a barroom cutaway to those inane cartoon ads Dailey’s Doug Hallerton has inflicted upon a nationwide audience. It’s even implied that Doug’s marriage might become a direct casualty of his misdirected creative energies. His whole "life of degradation" speech at the end is really Doug’s confession of having degraded himself through an association with television. In fact, all three principals react to their video debuts as though they’d been tossed head-first into the ninth ring of hell. Only a questionably motivated donnybrook and full-scale disruption of this vulgar broadcast can redeem their integrity.

Michael Kidd had to feel some resentment after four day’s rehearsal and a day and a half shooting on his solo number, "Jack and The Space Giants" (shown here), only to see the number excised at Kelly’s insistence. The footage is included as an extra on the DVD, and Kidd’s dexterity with kitchen utensils is a sight to behold --- he actually reminded me of those acrobatic routines Roscoe Arbuckle used to execute when playing a cook and/or waiter in the silent days. They say Kelly nixed the act because Kidd employed little kids as an appreciative on-screen audience, and Gene couldn’t abide the notion of anyone else using moppets for props. That was his specialty. Dan Dailey’s big lampshade routine nearly went into Gene's dustbin as well, but co-director Stanley Donen fought to keep it. He described the job with Kelly thus: It was an absolute, one-hundred percent nightmare, and this within twenty years after the 1955 experience, when both men were still active in the business and would presumably encounter one another (at least socially) from time to time. You’d have to assume Kelly was a real pill on this show, but that roller-skate number sure redeems him for me. It’s got to be among the top three of any dances the man ever performed. Even if It’s Always Fair Weather were an otherwise lousy movie (which it certainly is not), this segment would place it among the immortals.

The expansive ad you see here was actually a fold-out herald inserted into newspapers, grocery bags, mailboxes --- you name it --- and the cost to exhibitors was $5.25 per one thousand. A price increase went into effect on July 1, 1955 --- from that date they'd be $9.25 per K. The stars with outstretched hands around the title were a less than inspired marketing image used for virtually all the poster art, even making its way to the recent DVD cover. Overrall a pretty anemic campaign, and that probably had something to do with resulting weak attendance. One remarkable exception are the fantastic door panels illustrated here. Each of these six in the set were full color and stood sixty inches high, by twenty inches across. They are gorgeous and almost impossible to find today. Metro provided these on most of its big pictures between 1950 and 1955. None of them were cheap, so exhibitors used door panels sparingly. I found a bunch scrounging an old theatre some thirty years ago, and believe me, they’re incredible. This Wonderbread tie-in with Cyd Charisse makes me wonder --- was Cyd informed as to each ad bearing her image? I suppose she signed a release. Maybe not. Probably sitting at home reading Woman’s Home Companion, and there it was. The "Weather Bally" was inevitable, I suppose, but would it have lured patrons? Doubt it. If anything drove off business, it was probably the fact George Murphy was giving away the movie on TV’s MGM Parade, an 1955-56 ABC series operating on the assumption home audiences would happily sit through old theatrical shorts, heavily abridged features, and random clips just to get a glimpse of Metro’s forthcoming releases. Two of the episodes featured the best songs from It’s Always Fair Weather in their virtual entirety (that’s George Murphy and Cyd Charrise setting one up for the viewers). Schizophrenic Metro was feeding the video monster even as they tried so desperately to resist the erosion it was causing for their boxoffice. Yet another number was a gratuity for audiences in an MGM Cinemascope short made the same year, Salute To The Theatres, in which Murphy visits the set (shown here) and persuades Gene Kelly to make with a free song and dance. Poor George was like the tent show barker that gives up the whole show on the outside before anyone has a chance to pay for the privilege of coming inside.