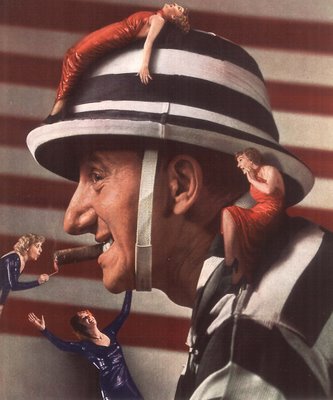

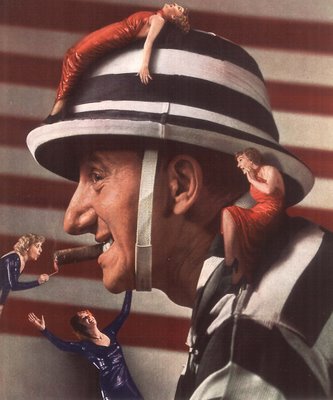

A Little Something To Disturb Your SleepThe more I look at this bizarre portrait of Jimmy Durante, the more creeped out I get. No doubt the idea was to spoof his self-promoted image as an irresistible magnet for beautiful women. Must have been taken sometime in the late fifties. Buster Keaton fans were never able to warm up to this guy. Durante really walked all over Keaton in those MGM features they did together. I’m looking for the best word to describe Durante beyond his first five minutes in any movie --- irritating? A little of this comic goes a long way for me…

A Little Something To Disturb Your SleepThe more I look at this bizarre portrait of Jimmy Durante, the more creeped out I get. No doubt the idea was to spoof his self-promoted image as an irresistible magnet for beautiful women. Must have been taken sometime in the late fifties. Buster Keaton fans were never able to warm up to this guy. Durante really walked all over Keaton in those MGM features they did together. I’m looking for the best word to describe Durante beyond his first five minutes in any movie --- irritating? A little of this comic goes a long way for me…

We Want Our Fu Manchus!

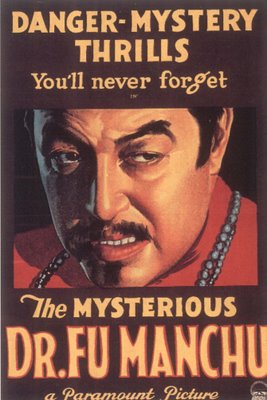

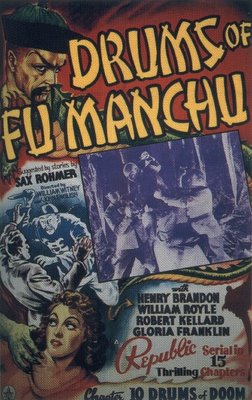

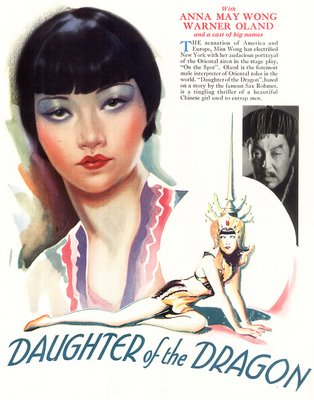

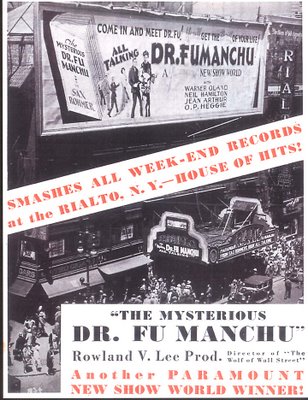

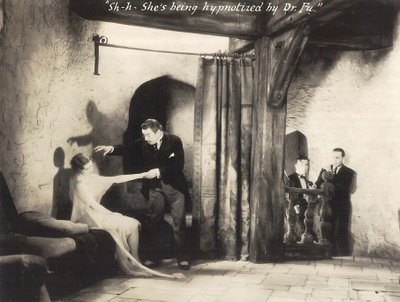

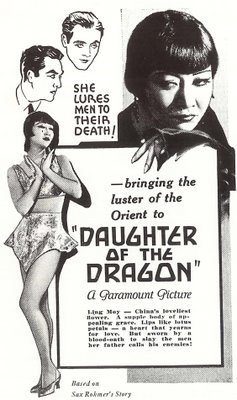

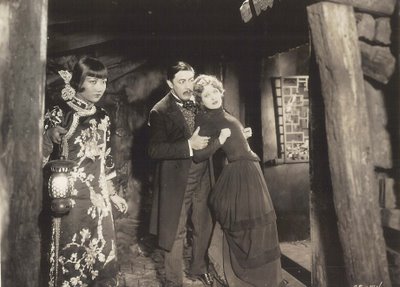

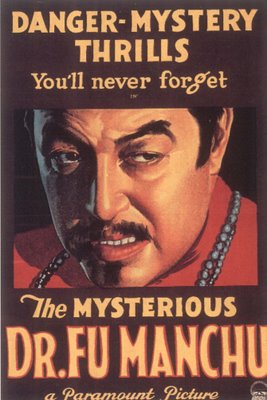

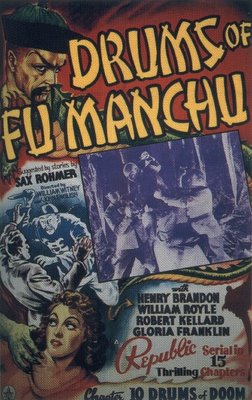

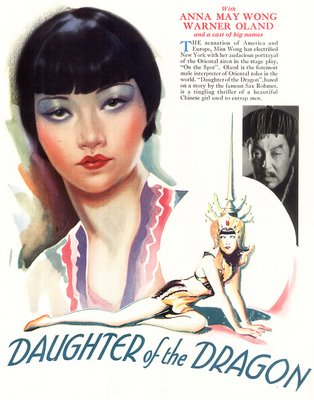

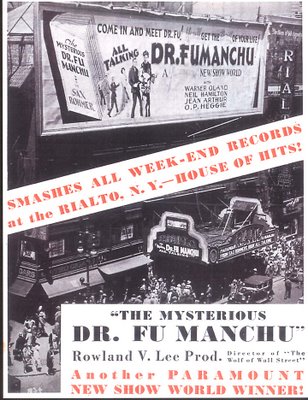

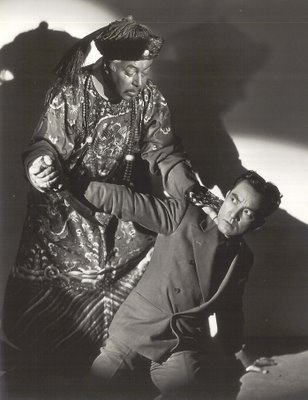

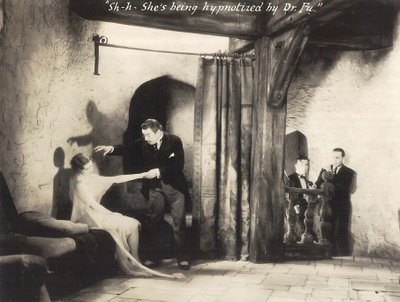

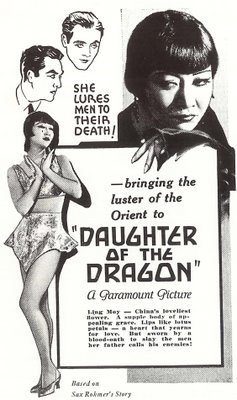

We Want Our Fu Manchus! It's frustrating to write about films we can't all see. I’d read about the Paramount Fu Manchu series for years, but had never gotten to look at any of them, other than a bootlegged DVD of The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu I viewed just today. So what’s the holdup with these early sound thrillers? Why are all three unavailable beyond occasional archival showings? The problem apparently lies with the Sax Rohmer estate. He conceived the character and wrote the novels upon which the movies were based. It would seem that Paramount’s use of the properties was limited to the initial release of the three features they produced --- those being The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929), Return Of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930), and Daughter Of The Dragon (1931). The literary rights reverted back to Rohmer and consigned the films to a sort of ownership Twilight Zone wherein all three exist, but none can be televised or distributed on DVD. The same cloud hovers over Republic’s 1940 serial, Drums Of Fu Manchu, a fan favorite that has only been available on gray-market discs of indifferent quality. UCLA Film Archives has excellent preservation materials on all these subjects, but must confine their exhibition to on-site festivals and infrequent loans to other institutions. Even though they hold the original nitrate negative for Drums Of Fu Manchu, UCLA has been unable to confirm the current rights holder, and any concerted effort to do so would be both time-consuming and expensive. The question ultimately becomes --- is any Republic serial worth this? Universal is the present owner of the three features; this goes back to MCA’s acquisition of them along with the rest of Paramount’s pre-1949 package in 1958. The Fu Manchus could not be released to television at that time, although Daughter Of The Dragon did go into the syndicated package by mistake, the absence of Fu’s name in the title allowing it to slip through. Consequently, there were nice 16mm prints of this one in circulation among collectors. The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu and Return Of Dr. Fu Manchu were, to my knowledge, not shown on television, and never available for rental, theatrical or otherwise. Preservation for the three features was made possible by donations from publisher Hugh Hefner in the late nineties, and they were shown at UCLA’s annual festival in 2000.

It's frustrating to write about films we can't all see. I’d read about the Paramount Fu Manchu series for years, but had never gotten to look at any of them, other than a bootlegged DVD of The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu I viewed just today. So what’s the holdup with these early sound thrillers? Why are all three unavailable beyond occasional archival showings? The problem apparently lies with the Sax Rohmer estate. He conceived the character and wrote the novels upon which the movies were based. It would seem that Paramount’s use of the properties was limited to the initial release of the three features they produced --- those being The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929), Return Of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930), and Daughter Of The Dragon (1931). The literary rights reverted back to Rohmer and consigned the films to a sort of ownership Twilight Zone wherein all three exist, but none can be televised or distributed on DVD. The same cloud hovers over Republic’s 1940 serial, Drums Of Fu Manchu, a fan favorite that has only been available on gray-market discs of indifferent quality. UCLA Film Archives has excellent preservation materials on all these subjects, but must confine their exhibition to on-site festivals and infrequent loans to other institutions. Even though they hold the original nitrate negative for Drums Of Fu Manchu, UCLA has been unable to confirm the current rights holder, and any concerted effort to do so would be both time-consuming and expensive. The question ultimately becomes --- is any Republic serial worth this? Universal is the present owner of the three features; this goes back to MCA’s acquisition of them along with the rest of Paramount’s pre-1949 package in 1958. The Fu Manchus could not be released to television at that time, although Daughter Of The Dragon did go into the syndicated package by mistake, the absence of Fu’s name in the title allowing it to slip through. Consequently, there were nice 16mm prints of this one in circulation among collectors. The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu and Return Of Dr. Fu Manchu were, to my knowledge, not shown on television, and never available for rental, theatrical or otherwise. Preservation for the three features was made possible by donations from publisher Hugh Hefner in the late nineties, and they were shown at UCLA’s annual festival in 2000.

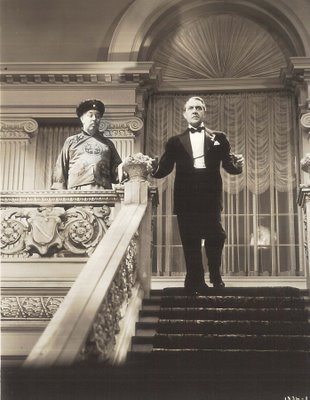

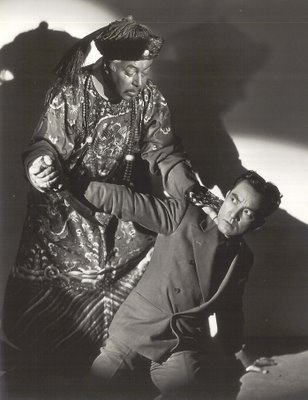

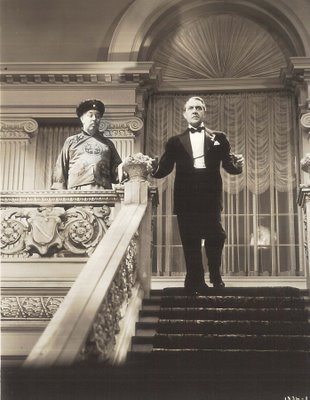

I’d like to report that progress is being made toward a general revival of the Fu Manchus, but Universal isn’t likely to expend that sort of time and expense for the benefit of such relics as these. Never mind the racial and ethnic sensitivities involved --- these are seriously dated shows. Folks that read Greenbriar Picture Shows might well stand on line to see them, but for civilians, they’d seem beyond ancient. Maybe I’ve dwelled in cinematic tombs too long, but I was actually surprised at what a vigorous film The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu turned out to be, even in my disadvantaged position of watching a lousy third-generation DVD. Candor forces me to admit that Warner Oland could read the daily classifieds and I’d be entranced. He’s one of those actors who need merely enter a room to dominate it. His Fu Manchu is much like the genial Charlie Chan with occasionally sinister overlays. The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu was released in August 1929, so we must naturally make allowances for Paramount’s uncertainty with sound, but it’s a tremendous advance over talkies of only a few months earlier, and has a lot more energy than, say, The (glacial) Canary Murder Case. There’s a dynamic first reel that sets up Fu’s motivation for a lifetime of seeking revenge against the accursed white race, and plenty of cliffside mansion suspense later on. Maybe I was just in a good mood when I watched this, because I even enjoyed Neil Hamilton’s occasional tripping over his lines. There’s an indefinable charm to these lurching, show-must-go-on early talkers --- actors and directors giving their all against what must have seemed overwhelming odds.

I’d like to report that progress is being made toward a general revival of the Fu Manchus, but Universal isn’t likely to expend that sort of time and expense for the benefit of such relics as these. Never mind the racial and ethnic sensitivities involved --- these are seriously dated shows. Folks that read Greenbriar Picture Shows might well stand on line to see them, but for civilians, they’d seem beyond ancient. Maybe I’ve dwelled in cinematic tombs too long, but I was actually surprised at what a vigorous film The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu turned out to be, even in my disadvantaged position of watching a lousy third-generation DVD. Candor forces me to admit that Warner Oland could read the daily classifieds and I’d be entranced. He’s one of those actors who need merely enter a room to dominate it. His Fu Manchu is much like the genial Charlie Chan with occasionally sinister overlays. The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu was released in August 1929, so we must naturally make allowances for Paramount’s uncertainty with sound, but it’s a tremendous advance over talkies of only a few months earlier, and has a lot more energy than, say, The (glacial) Canary Murder Case. There’s a dynamic first reel that sets up Fu’s motivation for a lifetime of seeking revenge against the accursed white race, and plenty of cliffside mansion suspense later on. Maybe I was just in a good mood when I watched this, because I even enjoyed Neil Hamilton’s occasional tripping over his lines. There’s an indefinable charm to these lurching, show-must-go-on early talkers --- actors and directors giving their all against what must have seemed overwhelming odds.

One of the great exhibition miracles was performed in August 1929 with the trailer for The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu. Ernest Morrison of Dallas’ Greater Palace Theatre followed his customary newsreel with a bath of weird green light throughout the auditorium as his screen opened up to full Magnascope proportions. This was basically a matter of blowing up your picture to fill the entire proscenium and was used primarily for spectacular action scenes, such as the dogfights in Wings. Morrison filled the theatre with sounds of police sirens as the preview for The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu flashed on the screen. The Greater Palace’s live orchestra then went into an agitato theme until the first talking sequence of the trailer began. All the house lights were extinguished at this point, and red footlights began flashing on and off, with the further enhancement of two green spotlights operated from the booth --- roaming across the stage and all around the auditorium. The impact caused women to scream, and an otherwise unassuming trailer became the highlight of the program.

One of the great exhibition miracles was performed in August 1929 with the trailer for The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu. Ernest Morrison of Dallas’ Greater Palace Theatre followed his customary newsreel with a bath of weird green light throughout the auditorium as his screen opened up to full Magnascope proportions. This was basically a matter of blowing up your picture to fill the entire proscenium and was used primarily for spectacular action scenes, such as the dogfights in Wings. Morrison filled the theatre with sounds of police sirens as the preview for The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu flashed on the screen. The Greater Palace’s live orchestra then went into an agitato theme until the first talking sequence of the trailer began. All the house lights were extinguished at this point, and red footlights began flashing on and off, with the further enhancement of two green spotlights operated from the booth --- roaming across the stage and all around the auditorium. The impact caused women to scream, and an otherwise unassuming trailer became the highlight of the program.

Sax Rohmer died in 1959. Most of his Fu Manchu stories were written in the twenties. Some of these are now in the public domain, but the character of Fu Manchu is still protected. If Universal, or anyone else, were inclined to pursue the rights for the three Paramount features or the Republic serial, they’d have to track down the legal representatives of Rohmer’s estate. From the best I could determine, his interests are represented by The Author’s League Of America (HERE). There’s also a British concern, The Society Of Authors, HERE, that specifically lists Rohmer’s estate on their website. I don’t know if anyone’s approached these entities about clearing the way for a DVD release of these titles, but it would be a wonderful thing if they could. These orphaned shows have been out of circulation far too long. Paramount’s features would make a nifty box set (they could even include Oland’s comedic skit as Fu Manchu in Paramount On Parade as an extra), and the Republic serial would make a lot of chapterplay enthusiasts very happy indeed. In the meantime, those of us not within driving distance of UCLA will have to make do with the enticing images shown here and whatever bootlegged videos can be scrounged up on e-bay.

Sax Rohmer died in 1959. Most of his Fu Manchu stories were written in the twenties. Some of these are now in the public domain, but the character of Fu Manchu is still protected. If Universal, or anyone else, were inclined to pursue the rights for the three Paramount features or the Republic serial, they’d have to track down the legal representatives of Rohmer’s estate. From the best I could determine, his interests are represented by The Author’s League Of America (HERE). There’s also a British concern, The Society Of Authors, HERE, that specifically lists Rohmer’s estate on their website. I don’t know if anyone’s approached these entities about clearing the way for a DVD release of these titles, but it would be a wonderful thing if they could. These orphaned shows have been out of circulation far too long. Paramount’s features would make a nifty box set (they could even include Oland’s comedic skit as Fu Manchu in Paramount On Parade as an extra), and the Republic serial would make a lot of chapterplay enthusiasts very happy indeed. In the meantime, those of us not within driving distance of UCLA will have to make do with the enticing images shown here and whatever bootlegged videos can be scrounged up on e-bay.

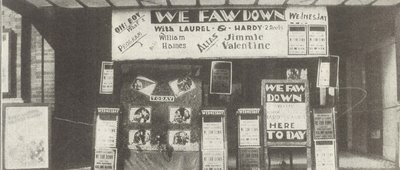

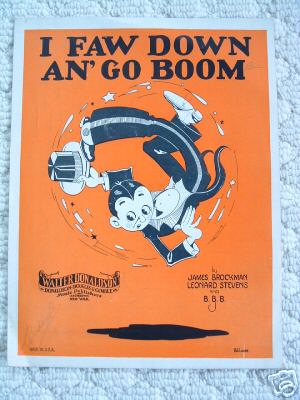

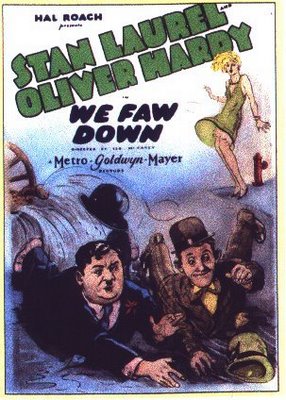

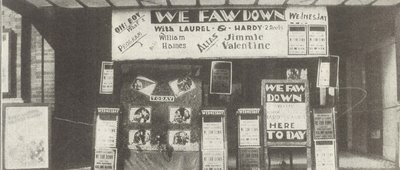

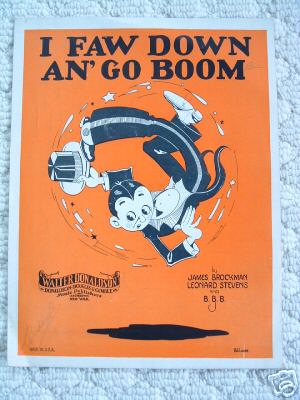

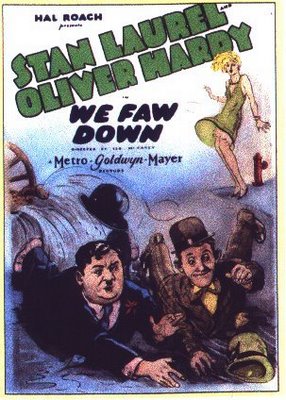

Fads and Flaps Of YesteryearHaving grown up in a world saturated by media, we’ve all seen the overnight assault of new fads and catchphrases inspired by music, movies, and television shows. I can remember walking through my neighborhood in the Fall of 1965, wondering why all the kids now prefaced observations with, Would you believe …?, and footnoted every conversation with Sorry About That, Chief. By the fifth such encounter, I’d finally assembled the puzzle. Seems everyone had watched Get Smart the night before, and I was the final initiate to a whole new vocabulary shared by every hep kid on the street. We assume these pop cultural tom-toms beat exclusively for our generation, but the Roaring 20’s had its own complement of hep kids as well, all of them hot wired to radios and Victrolas long before there was TV and internet downloads. Exhibitor Wally Akin of Kennett, Missouri had his own Get Smart experience in April 1929 as he ambled down the main street of that small town trying to figure out how to sell his upcoming program at the Palace Theatre. I overheard a little girl say, "We faw down and go boom", Wally recalled. Before I walked three city blocks there were at least ten more children saying the same thing … Looking over my bookings, I found we had Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in a two-reel comedy titled "We Faw Down." This phrase being on the public’s tongue, I decided to feature the comedy instead of the long feature. The photo above shows the front display Wally came up with. His full-length show was Alias Jimmy Valentine with William Haines, but the real attraction was We Faw Down. We packed the theatre to the door on our worst night in the week. There’s no doubt but what showman Wally knew his onions --- surely Hal Roach's hot new comedy team caught the wave of that popular slang phrase as well. The thing had actually originated with a jazz tune called I Faw Down An’ Go Boom, by a pair of songwriters, James Brockman and Leonard Stevens. It flew up the charts by virtue of having been recorded by top artists of the day, including Billy Murray and The Midnight Ramblers, Annette Hanshaw, Eddie Cantor, and Cliff Edwards. By December 29, 1928, the day They Go Boom was released, everyone was whistling the nonsense ditty and borrowing variations of its title for conversational merriment.

Fads and Flaps Of YesteryearHaving grown up in a world saturated by media, we’ve all seen the overnight assault of new fads and catchphrases inspired by music, movies, and television shows. I can remember walking through my neighborhood in the Fall of 1965, wondering why all the kids now prefaced observations with, Would you believe …?, and footnoted every conversation with Sorry About That, Chief. By the fifth such encounter, I’d finally assembled the puzzle. Seems everyone had watched Get Smart the night before, and I was the final initiate to a whole new vocabulary shared by every hep kid on the street. We assume these pop cultural tom-toms beat exclusively for our generation, but the Roaring 20’s had its own complement of hep kids as well, all of them hot wired to radios and Victrolas long before there was TV and internet downloads. Exhibitor Wally Akin of Kennett, Missouri had his own Get Smart experience in April 1929 as he ambled down the main street of that small town trying to figure out how to sell his upcoming program at the Palace Theatre. I overheard a little girl say, "We faw down and go boom", Wally recalled. Before I walked three city blocks there were at least ten more children saying the same thing … Looking over my bookings, I found we had Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in a two-reel comedy titled "We Faw Down." This phrase being on the public’s tongue, I decided to feature the comedy instead of the long feature. The photo above shows the front display Wally came up with. His full-length show was Alias Jimmy Valentine with William Haines, but the real attraction was We Faw Down. We packed the theatre to the door on our worst night in the week. There’s no doubt but what showman Wally knew his onions --- surely Hal Roach's hot new comedy team caught the wave of that popular slang phrase as well. The thing had actually originated with a jazz tune called I Faw Down An’ Go Boom, by a pair of songwriters, James Brockman and Leonard Stevens. It flew up the charts by virtue of having been recorded by top artists of the day, including Billy Murray and The Midnight Ramblers, Annette Hanshaw, Eddie Cantor, and Cliff Edwards. By December 29, 1928, the day They Go Boom was released, everyone was whistling the nonsense ditty and borrowing variations of its title for conversational merriment.

The only thing Laurel and Hardy borrowed from I Faw Down An' Go Boom was (part of) its title. None of the lyrics would have lent themselves to silent comedy, as there were the usual naughty references common to jazz age songs, comical voice effects, and even a bit of japery about Wall Street. Actually, We Faw Down included its own music and effects score on recorded disc, being the second Laurel and Hardy with sound accompaniment. I Faw Down An’ Go Boom does not figure into the track, however. Instead, we hear That’s My Weakness Now over the titles, and again during the body of the short, along with several other popular tunes of the day. The short itself is the usual L&H domestic farce. If anything a little more ribald than usual, We Faw Down inspired this diatribe from an exhibitor in Spearville, Kansas. A comedy with just as suggestive scenes as it is possible to show without showing the real thing. Dirt, vulgar, obscene, and any other filthy name you wish to call it, it will fit every reel. W.J. Shoup’s furious manifesto ended with a call for industry, if not government, intervention --- What is needed in the making of pictures today is to clean house of most of the present producers, so we can have something to show our patrons that is entertaining and pleasing, without being so filthy. It’s possible Mr. Shoup of the DeLuxe Theatre was provoked by that closing gag where all the men jump out apartment windows sans trousers --- Where, oh where, was our censor board when this was passed? So not only were Laurel and Hardy current with pop culture references --- they were cutting edge in matters of bawdy content as well. Looks like we’ve been underestimating these boys!

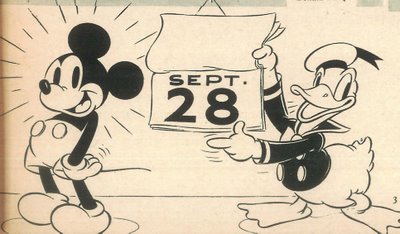

As more bands covered I Faw Down An’ Go Boom, its prominence continued through 1929. Laurel and Hardy would go back to the well at least twice. The Hollywood Revue Of 1929 found the comedians engaged in a bungled magic act that culminates with Oliver Hardy falling into an oversized cake, then plaintively looking at the camera. I faw down and go splat, he says. To modern viewers, it’s an uncharacteristic (if not off-putting) line, but 1929 audiences got the joke and surely had their laugh. September 21, 1929 saw the release of They Go Boom, a talking Laurel and Hardy that utilized another spin on the song title but nothing else. Fads had more longevity in those days when it took longer for them to penetrate the marketplace. Even as late as 1945’s Warner cartoon, A Gruesome Twosome, Tweetie Pie was lamenting the poor putty tat that fell down and went boom. Google the venerable phrase right now and you’ll find numerous modern references. Referencing We Faw Down and They Go Boom will take you to a DVD series called The Lost Films Of Laurel and Hardy. These are, for the most part, silent comedies, but a few talkies turn up in this group as well, including They Go Boom (on Volume 4). The only source for We Faw Down with the original music/effects score is a German DVD (the one included in The Lost Films Of Laurel and Hardy has a random track culled from other discs). If you have a multi-region player, it’s well worth the trouble to get the German DVD. We Faw Down was the last of the synchronized scores awaiting rediscovery. It plays much better with this original accompaniment. There’s no dialogue, of course, but plenty of knocks on doors, telephones ringing, etc., and even dubbed laughter for both Laurel and Hardy in several scenes (not their own, but a neat effect). Tracks for seven of these comedies have now been retrieved after years of apparent loss --- Habeas Corpus, We Faw Down, Liberty, Wrong Again, That’s My Wife, Bacon Grabbers, and Angora Love. Each are enhanced by the vintage music and sound punctuation. I’m told that all of these, plus the balance of Laurel and Hardy’s silent output, is being remastered for a forthcoming DVD box set. I hope this will come sooner rather than later. A lot of us are surely looking forward to that release.

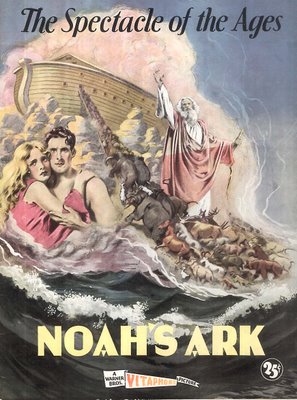

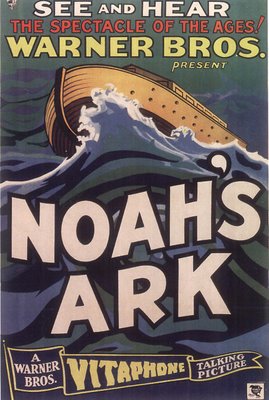

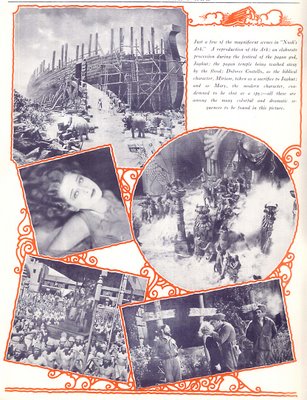

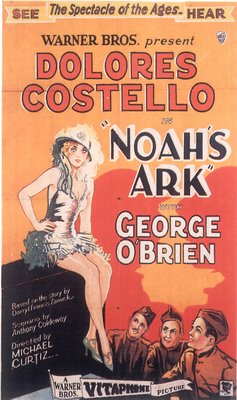

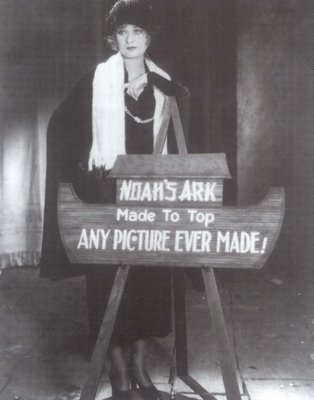

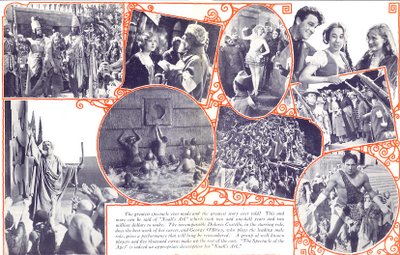

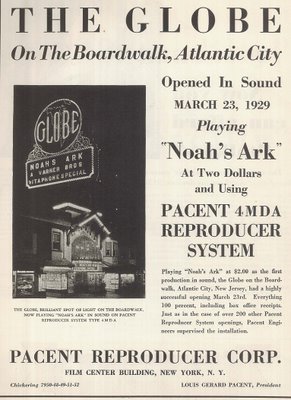

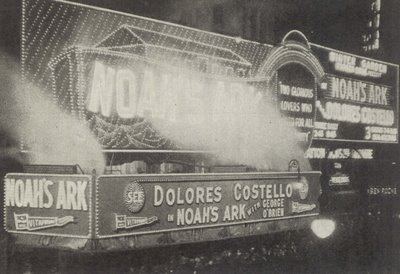

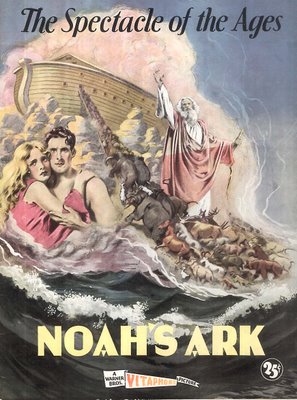

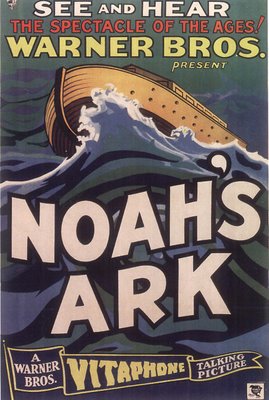

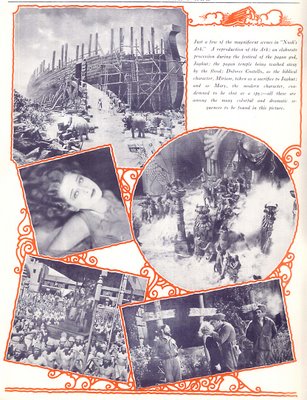

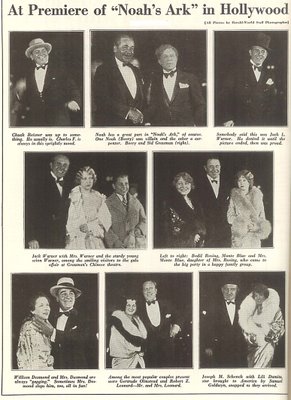

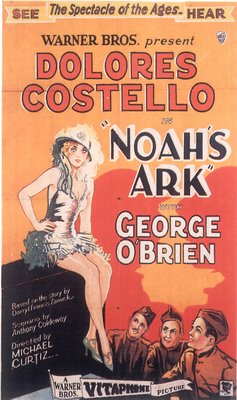

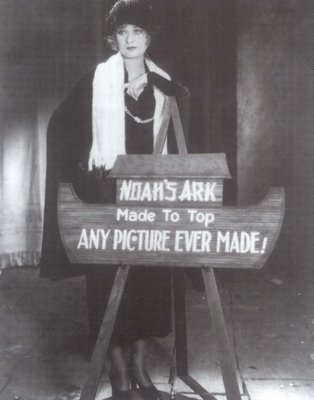

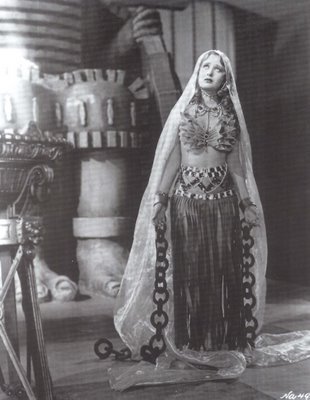

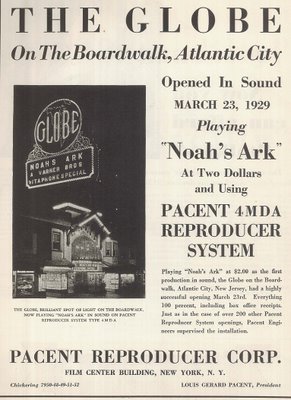

Life Was Cheap On Noah's Ark Once upon a time there were epics like Noah’s Ark. So many, in fact, that we took them for granted. This particular one cost a million dollars and at least two lives. The money spent was well publicized. Those who died or were injured were not. Names as well as their specific fates are unknown today. One man was said to have lost a leg. None of this story got out at the time. Whatever documentation arose from the incident was no doubt purged from studio files long ago. It’s often said they got away with murder in Hollywood --- here’s a show to back up that assertion. Director Michael Curtiz turned massive drums of water loose on 5000 screaming extras, and it was every man for himself. In a latter day landscape faked up with computer generated cataclysms, it’s truly startling to see a real flood enacted on screen, with people actually struggling for their lives. I got fascinated with this movie all over again while looking into Dolores Costello’s career with Warner Bros. She still remembered the horror of Noah’s Ark fifty years after it was completed. Mud, Blood, and Flood was what she called it. Wounded extras laid outside her dressing room door as fleets of ambulances carried away victims of the carnage. It must have taken some adroit handling on Warners' part to keep all this under wraps.

Life Was Cheap On Noah's Ark Once upon a time there were epics like Noah’s Ark. So many, in fact, that we took them for granted. This particular one cost a million dollars and at least two lives. The money spent was well publicized. Those who died or were injured were not. Names as well as their specific fates are unknown today. One man was said to have lost a leg. None of this story got out at the time. Whatever documentation arose from the incident was no doubt purged from studio files long ago. It’s often said they got away with murder in Hollywood --- here’s a show to back up that assertion. Director Michael Curtiz turned massive drums of water loose on 5000 screaming extras, and it was every man for himself. In a latter day landscape faked up with computer generated cataclysms, it’s truly startling to see a real flood enacted on screen, with people actually struggling for their lives. I got fascinated with this movie all over again while looking into Dolores Costello’s career with Warner Bros. She still remembered the horror of Noah’s Ark fifty years after it was completed. Mud, Blood, and Flood was what she called it. Wounded extras laid outside her dressing room door as fleets of ambulances carried away victims of the carnage. It must have taken some adroit handling on Warners' part to keep all this under wraps.

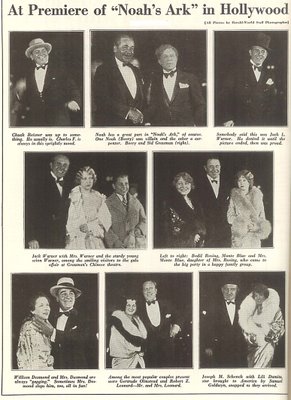

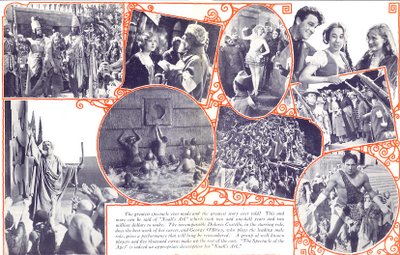

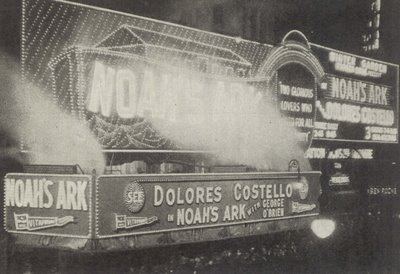

Noah’s Ark was designed for all-out showmanship. The show started outside New York’s Winter Garden Theatre with lighted displays and a forty-foot blimp hovering over the marquee. Eight "sunlight arcs" poured changing colors on the leviathan as wires caused it to dip and sway toward a giant replica of the ark electrified with rain effects and clouds of steam. Inside the auditorium, more deluge greeted the audience as wind and water signaled the Vitaphone overture. First-nighters paid eleven dollars a seat, and all were filled. Subsequent tickets went for two dollars, which caused resentment among reviewers whose own lukewarm response to Noah’s Ark was in part a rebuke of Warners for having oversold what these critics considered an ordinary and derivative picture. Seventy-seven years have a way of changing perspectives however --- were it remade today, Noah’s Ark would no doubt invite all sorts of controversy, considering the social agenda set forth in its dynamic opening reel. After a sobering glimpse of biblical era excesses, we’re treated to a montage of jazz age depravity. The Worship of the Golden Calf Remains Man’s Religion is the title preceding a frenzied day on Wall Street, where barter and loss of fortunes result in bloodshed on front steps of the exchange. Is this chaos and immorality a natural consequence of capitalism gone mad? Further dissolves depicting suicide, prostitution, and alcohol abuse suggests it is. Here’s a society badly in need of overhaul --- and this was months before the crash. Was Warners looking into a crystal ball? Theirs is a merciless commentary. Skyscrapers are modern Towers of Babel. America’s headed down a ticker tape highway to hell. If anyone tried selling a philosophy like this today, the very least they’d get is a good media spank for playing politics. Unsubtle as it is, Noah’s Ark packs a mean wallop with that opening, so much so that we’re almost sorry to see it veer off into a more prosaic World War One story for the hour or so that follows.

Noah’s Ark was designed for all-out showmanship. The show started outside New York’s Winter Garden Theatre with lighted displays and a forty-foot blimp hovering over the marquee. Eight "sunlight arcs" poured changing colors on the leviathan as wires caused it to dip and sway toward a giant replica of the ark electrified with rain effects and clouds of steam. Inside the auditorium, more deluge greeted the audience as wind and water signaled the Vitaphone overture. First-nighters paid eleven dollars a seat, and all were filled. Subsequent tickets went for two dollars, which caused resentment among reviewers whose own lukewarm response to Noah’s Ark was in part a rebuke of Warners for having oversold what these critics considered an ordinary and derivative picture. Seventy-seven years have a way of changing perspectives however --- were it remade today, Noah’s Ark would no doubt invite all sorts of controversy, considering the social agenda set forth in its dynamic opening reel. After a sobering glimpse of biblical era excesses, we’re treated to a montage of jazz age depravity. The Worship of the Golden Calf Remains Man’s Religion is the title preceding a frenzied day on Wall Street, where barter and loss of fortunes result in bloodshed on front steps of the exchange. Is this chaos and immorality a natural consequence of capitalism gone mad? Further dissolves depicting suicide, prostitution, and alcohol abuse suggests it is. Here’s a society badly in need of overhaul --- and this was months before the crash. Was Warners looking into a crystal ball? Theirs is a merciless commentary. Skyscrapers are modern Towers of Babel. America’s headed down a ticker tape highway to hell. If anyone tried selling a philosophy like this today, the very least they’d get is a good media spank for playing politics. Unsubtle as it is, Noah’s Ark packs a mean wallop with that opening, so much so that we’re almost sorry to see it veer off into a more prosaic World War One story for the hour or so that follows.

That wartime and biblical stuff rang a bell for 1929 audiences. They’d seen most of it before in The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Big Parade, and any number of inbred blockbusters that had so far racked up huge grosses. Noah’s Ark never pretended to be anything other than grand spectacle. What it stole would later be stolen from it. Pagan soldiers burn out George O’Brien’s eyes and bind him to a gristmill. DeMille got even for Warners’ pillage from his own biblical epics by lifting this plot device wholesale and using it in Samson and Delilah --- twenty years hence. Producers knew better than to be too original with this sort of material --- patrons came with certain expectations and expected them to be met. In Noah's Ark, trains are wrecked, maidens are abducted, and villains die horribly. Truly an exhibitor’s dream picture. Even against that million dollar negative (Warner’s biggest outlay as of that year), there was a profit of $523,000. Foreign sales were stimulated when director Michael Curtiz appeared on camera and narrated a series of Vitaphone trailers (in the appropriate language) for Hungarian, French, German, and Austrian theatres. Dialogue sequences spurred the domestic boxoffice. Isolated here and there, and accomplishing nothing other than bringing the narrative to a dead halt, they were a necessary evil and useful sop for fans expecting at least a little recorded bang for their buck. Poor Dolores Costello once again took a critical rapping (emotionless, stilted delivery), but the climactic flood more than put over the sock everyone had paid to see. For all his culpability regarding those doomed extras, Curtiz surely knew how to construct his epics. What a shame this Noah’s Ark had to run aground for sixty years after its initial release. It’s only by way of UCLA’s restoration miracle that we now can now recapture some semblance of what audiences enjoyed in 1929.

That wartime and biblical stuff rang a bell for 1929 audiences. They’d seen most of it before in The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Big Parade, and any number of inbred blockbusters that had so far racked up huge grosses. Noah’s Ark never pretended to be anything other than grand spectacle. What it stole would later be stolen from it. Pagan soldiers burn out George O’Brien’s eyes and bind him to a gristmill. DeMille got even for Warners’ pillage from his own biblical epics by lifting this plot device wholesale and using it in Samson and Delilah --- twenty years hence. Producers knew better than to be too original with this sort of material --- patrons came with certain expectations and expected them to be met. In Noah's Ark, trains are wrecked, maidens are abducted, and villains die horribly. Truly an exhibitor’s dream picture. Even against that million dollar negative (Warner’s biggest outlay as of that year), there was a profit of $523,000. Foreign sales were stimulated when director Michael Curtiz appeared on camera and narrated a series of Vitaphone trailers (in the appropriate language) for Hungarian, French, German, and Austrian theatres. Dialogue sequences spurred the domestic boxoffice. Isolated here and there, and accomplishing nothing other than bringing the narrative to a dead halt, they were a necessary evil and useful sop for fans expecting at least a little recorded bang for their buck. Poor Dolores Costello once again took a critical rapping (emotionless, stilted delivery), but the climactic flood more than put over the sock everyone had paid to see. For all his culpability regarding those doomed extras, Curtiz surely knew how to construct his epics. What a shame this Noah’s Ark had to run aground for sixty years after its initial release. It’s only by way of UCLA’s restoration miracle that we now can now recapture some semblance of what audiences enjoyed in 1929.

Noah’s Ark’s initial deliverer was Robert Youngson, who’d championed the film during the early fifties when he was employed in Warner Bros.’ short subjects department. A lifelong film buff and later producer of all those fabulous comedy compilations, Youngson edited a group of one-reel subjects culled from silent spectaculars such as Don Juan, Isle Of Lost Ships, Old San Francisco, and Noah’s Ark. When Associated Artists bought the Warners pre-49 library for television release in 1956, they ended up with the surviving silent negatives as well, including Noah’s Ark. While 16mm prints were being prepared for TV sales, AAP established a subsidiary called Dominant Pictures, whose mission was to squeeze whatever theatrical bookings they could out of the old Warner product before the video dump. Youngson approached Dominant with his idea of re-editing and "modernizing" Noah’s Ark for a 35mm re-issue. Since they now owned the picture anyway, there was little to lose. The 1957 version would be shorn of all intertitles and talking sequences. Newsreel narrator Dwight Weist provided non-stop explanation and commentary throughout a truncated Noah’s Ark, but this was all the access we’d have to the film until Robert Gitt and the UCLA restoration team got hold of the project in 1988. What’s now shown regularly on TCM is their handiwork, and other than a little missing footage here and there, it’s the complete 1929 general release version. If ever there was a title worth canvassing your TCM schedule for, Noah’s Ark is it. I’d like to think there’s a DVD release somewhere in the offing as well. The definitive production and restoration history of Noah's Ark was written by Scott MacQueen and published in Issue 12 (Winter 1991-92) of The Perfect Vision. A great piece of scholarship and highly recommended.

Noah’s Ark’s initial deliverer was Robert Youngson, who’d championed the film during the early fifties when he was employed in Warner Bros.’ short subjects department. A lifelong film buff and later producer of all those fabulous comedy compilations, Youngson edited a group of one-reel subjects culled from silent spectaculars such as Don Juan, Isle Of Lost Ships, Old San Francisco, and Noah’s Ark. When Associated Artists bought the Warners pre-49 library for television release in 1956, they ended up with the surviving silent negatives as well, including Noah’s Ark. While 16mm prints were being prepared for TV sales, AAP established a subsidiary called Dominant Pictures, whose mission was to squeeze whatever theatrical bookings they could out of the old Warner product before the video dump. Youngson approached Dominant with his idea of re-editing and "modernizing" Noah’s Ark for a 35mm re-issue. Since they now owned the picture anyway, there was little to lose. The 1957 version would be shorn of all intertitles and talking sequences. Newsreel narrator Dwight Weist provided non-stop explanation and commentary throughout a truncated Noah’s Ark, but this was all the access we’d have to the film until Robert Gitt and the UCLA restoration team got hold of the project in 1988. What’s now shown regularly on TCM is their handiwork, and other than a little missing footage here and there, it’s the complete 1929 general release version. If ever there was a title worth canvassing your TCM schedule for, Noah’s Ark is it. I’d like to think there’s a DVD release somewhere in the offing as well. The definitive production and restoration history of Noah's Ark was written by Scott MacQueen and published in Issue 12 (Winter 1991-92) of The Perfect Vision. A great piece of scholarship and highly recommended.

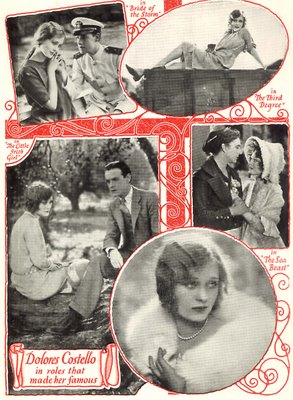

Monday Glamour Starter --- Dolores Costello

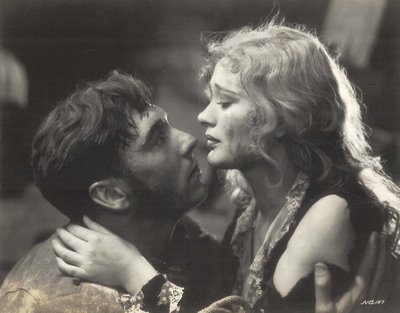

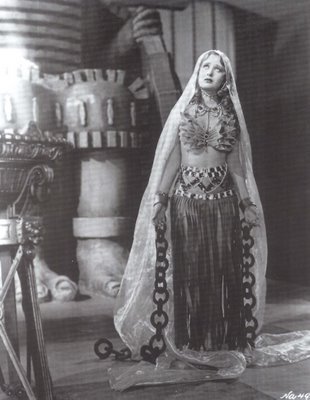

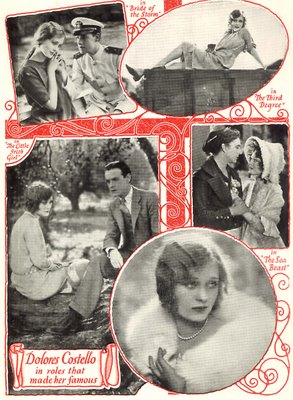

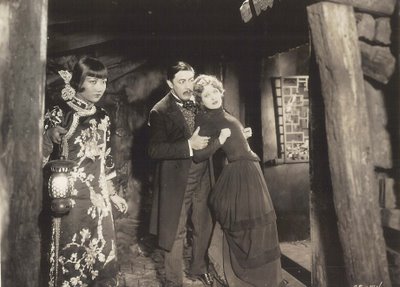

Monday Glamour Starter --- Dolores Costello Dolores Costello was another of those silent stars that had a bad talkie experience. She also had a bad John Barrymore experience, as had others. Life between the two was pretty harrowing for those years when she was Warner Bros.’ biggest feminine lead and married to that profile of profiles. By the time she was in her mid-thirties, Dolores was disposed of both Barrymore and her own stardom. Surely there were lessons along the way for her to pass down to various troubled offspring in that tormented theatrical family, though she’d share few of these with a public who’d by now forgotten the most preposterously lovely creature in all the world (John Barrymore’s initial words in describing Dolores). Her fashion in dewy-eyed, patrician beauties was a vogue that came and went as quickly as talkies arrived to supplant the silents. Were it not for the all-too brief rapture of marriage to J.B., she might have suffered the career loss more grievously, but in the end, she was content in her retreat to the modest quiet of an avocado ranch in Fallbrook, California. There were shelves of Jack’s old first editions if a quick infusion of cash was needed, but otherwise, I’d like to imagine Dolores enjoyed a largely secluded retirement after the fashion of Harold Bissonette among his orange groves at the happy end of It’s A Gift.

Dolores Costello was another of those silent stars that had a bad talkie experience. She also had a bad John Barrymore experience, as had others. Life between the two was pretty harrowing for those years when she was Warner Bros.’ biggest feminine lead and married to that profile of profiles. By the time she was in her mid-thirties, Dolores was disposed of both Barrymore and her own stardom. Surely there were lessons along the way for her to pass down to various troubled offspring in that tormented theatrical family, though she’d share few of these with a public who’d by now forgotten the most preposterously lovely creature in all the world (John Barrymore’s initial words in describing Dolores). Her fashion in dewy-eyed, patrician beauties was a vogue that came and went as quickly as talkies arrived to supplant the silents. Were it not for the all-too brief rapture of marriage to J.B., she might have suffered the career loss more grievously, but in the end, she was content in her retreat to the modest quiet of an avocado ranch in Fallbrook, California. There were shelves of Jack’s old first editions if a quick infusion of cash was needed, but otherwise, I’d like to imagine Dolores enjoyed a largely secluded retirement after the fashion of Harold Bissonette among his orange groves at the happy end of It’s A Gift.

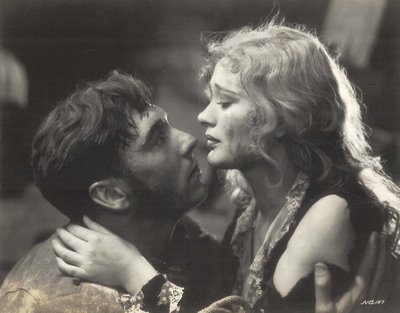

Dolores was predisposed to tolerate Barrymore’s excesses by her background, if not temperament, for she’d been born to a theatrical dynasty of her own. Maurice Costello was an ac-tor of the grand tradition being gently ushered offstage by changing audience tastes and his own proclivities toward roustabouting and cork removal. His brief respite with silent melodrama paved the way for little Dolores and sister Helene to enact child parts opposite their father, while bulldozer matriarch Mae Costello laid plans for eventual family life sans Maurice. Sure enough, by the time the girls were teens, he was off on permanent caprice and Mother took over. Dolores blossomed in the role of precocious chorine with George White’s Scandals, and made a fetching model for James Montgomery Flagg’s commercial art. These were the paths to a Warner contract that brought her into contact with John Barrymore, who immediately drafted Dolores as leading lady in The Sea Beast, his silent adaptation of Moby Dick. Dolores’ co-star, twenty plus years her senior, inspired the dead faint that ensued when he insisted on shooting their scorching love scenes first. Jack’s impassioned pursuit continued off the set as well, but it took three years, and a determined end run around Mae Costello, before Jack’s dream of a final consummation could be fulfilled. By this time, Dolores had become Warner’s most valuable feminine asset. With the arrival of sound, her prospects seemed limitless. Indeed, she would become the first major star recorded on Vitaphone after Jolson, but would Dolores share Al’s triumph on disc? She would not.

Dolores was predisposed to tolerate Barrymore’s excesses by her background, if not temperament, for she’d been born to a theatrical dynasty of her own. Maurice Costello was an ac-tor of the grand tradition being gently ushered offstage by changing audience tastes and his own proclivities toward roustabouting and cork removal. His brief respite with silent melodrama paved the way for little Dolores and sister Helene to enact child parts opposite their father, while bulldozer matriarch Mae Costello laid plans for eventual family life sans Maurice. Sure enough, by the time the girls were teens, he was off on permanent caprice and Mother took over. Dolores blossomed in the role of precocious chorine with George White’s Scandals, and made a fetching model for James Montgomery Flagg’s commercial art. These were the paths to a Warner contract that brought her into contact with John Barrymore, who immediately drafted Dolores as leading lady in The Sea Beast, his silent adaptation of Moby Dick. Dolores’ co-star, twenty plus years her senior, inspired the dead faint that ensued when he insisted on shooting their scorching love scenes first. Jack’s impassioned pursuit continued off the set as well, but it took three years, and a determined end run around Mae Costello, before Jack’s dream of a final consummation could be fulfilled. By this time, Dolores had become Warner’s most valuable feminine asset. With the arrival of sound, her prospects seemed limitless. Indeed, she would become the first major star recorded on Vitaphone after Jolson, but would Dolores share Al’s triumph on disc? She would not.

Dolores Costello got almost as raw a deal in talkies as Jack Gilbert, but it never bothered her as much. Neither she nor the technicians were prepared for the rushed debut of Tenderloin and Glorious Betsy, two that opened by the Spring of 1928, well before kinks were ironed out of Warner’s revolutionary sound process. Indeed, she got blame for much of what went wrong in the booth, be it scratchy discs, bad sync, or poor amplification. Mercy, mercy, have you no sister of your own? was a line delivered without incident on the set of Tenderloin, but it would achieve immediate catch-phrase immortality by the time it filtered through those speakers. Merthy, merthy, have you no thither of your own? Everyone assumed this was Dolores’ natural voice. Granted, her delivery needed work, but no more so than a hundred others in an industry filled with untrained and uncertain voices. Reviews now led off with "Poor Dolores…." Ridicule was heaped atop scorn. Director William DeMille caught Glorious Betsy in its Hollywood premiere and observed that Poor Dolores Costello’s excellent voice came out at times as a deep rich baritone, while Conrad Nagel thundered in a sub-human bass. It was obvious she’d been delivered up as a stalking horse to launch Vitaphone. After all, they had to put someone’s name on the marquee. Overexposure in hurried vehicles killed off many a lesser name, but few had withdrawn amidst such embarrassing catcalls. Poor Delores --- there are two opinions in Hollywood as to what her mike voice sounded like. One clique says it sounded like the barkings of a lonesome puppy; the others claim it reminded them of the time they sang "In The Shade Of the Old Apple Tree" through tissue paper folded over a comb. That was Photoplay’s assessment as of December 1930. By then, Dolores was on sabbatical --- undergoing intensive voice training, according to Warner publicists. By the time she came back (after a two year break), the parade had rushed her by. Even the studio’s assurance of a "new voice" could not dim audience memories of a faded star they’d laughed off the talking screen.

Dolores Costello got almost as raw a deal in talkies as Jack Gilbert, but it never bothered her as much. Neither she nor the technicians were prepared for the rushed debut of Tenderloin and Glorious Betsy, two that opened by the Spring of 1928, well before kinks were ironed out of Warner’s revolutionary sound process. Indeed, she got blame for much of what went wrong in the booth, be it scratchy discs, bad sync, or poor amplification. Mercy, mercy, have you no sister of your own? was a line delivered without incident on the set of Tenderloin, but it would achieve immediate catch-phrase immortality by the time it filtered through those speakers. Merthy, merthy, have you no thither of your own? Everyone assumed this was Dolores’ natural voice. Granted, her delivery needed work, but no more so than a hundred others in an industry filled with untrained and uncertain voices. Reviews now led off with "Poor Dolores…." Ridicule was heaped atop scorn. Director William DeMille caught Glorious Betsy in its Hollywood premiere and observed that Poor Dolores Costello’s excellent voice came out at times as a deep rich baritone, while Conrad Nagel thundered in a sub-human bass. It was obvious she’d been delivered up as a stalking horse to launch Vitaphone. After all, they had to put someone’s name on the marquee. Overexposure in hurried vehicles killed off many a lesser name, but few had withdrawn amidst such embarrassing catcalls. Poor Delores --- there are two opinions in Hollywood as to what her mike voice sounded like. One clique says it sounded like the barkings of a lonesome puppy; the others claim it reminded them of the time they sang "In The Shade Of the Old Apple Tree" through tissue paper folded over a comb. That was Photoplay’s assessment as of December 1930. By then, Dolores was on sabbatical --- undergoing intensive voice training, according to Warner publicists. By the time she came back (after a two year break), the parade had rushed her by. Even the studio’s assurance of a "new voice" could not dim audience memories of a faded star they’d laughed off the talking screen.

There were seven years with John Barrymore. She was said to have been positively saintly in her determined efforts to straighten him out, but as brother Lionel put it, Jack couldn’t stand monotony and he had a dread of being possessed by people. This was not a man capable of settling down, except with his drinking cohorts and a willing, short-term, concubine. Dolores tried again at performing, but age weighed heavier upon her than most, and that stoic beauty took on a matronly cast altogether suitable as Freddie Bartholomew’s mother in Little Lord Fauntleroy. Work was sporadic after that. There were unsettling stories about harsh make-up having damaged her face. Those unblemished cheeks were now deteriorated --- disintegrated (!) --- almost eaten away (!!). It all depended upon whom you read on the subject. The effects weren't apparent in The Magnificent Ambersons, but Orson Welles’ casting of her was more a matter of paying homage to the silent era than any recognition of talent. She would bow out for keeps after This Is The Army in 1943, and shunned interviews for decades thereafter. When Barrymore biographers approached her in the late seventies, Dolores was finally ready to talk, but no one seemed interested in her own career, other than Kevin Brownlow, whose Hollywood series captured the first and only on-camera appearance she’d make during the retirement years. Uncharitable observers said she looked like an old Irish washerwoman, which begs the question as to how many of us have had any actual exposure to old Irish washerwomen. If nothing else, she seems to have assumed mother Mae's role as stern family matriarch, and much of her old age was spent trying to extricate Barrymore children and grandchildren from various compromising situations. The lavish scrapbooks of her life with John Barrymore eventually saw publication in a recent oversized book celebrating the first family of acting, and it’s available HERE. Dolores died in 1979 at the age of seventy-five.

There were seven years with John Barrymore. She was said to have been positively saintly in her determined efforts to straighten him out, but as brother Lionel put it, Jack couldn’t stand monotony and he had a dread of being possessed by people. This was not a man capable of settling down, except with his drinking cohorts and a willing, short-term, concubine. Dolores tried again at performing, but age weighed heavier upon her than most, and that stoic beauty took on a matronly cast altogether suitable as Freddie Bartholomew’s mother in Little Lord Fauntleroy. Work was sporadic after that. There were unsettling stories about harsh make-up having damaged her face. Those unblemished cheeks were now deteriorated --- disintegrated (!) --- almost eaten away (!!). It all depended upon whom you read on the subject. The effects weren't apparent in The Magnificent Ambersons, but Orson Welles’ casting of her was more a matter of paying homage to the silent era than any recognition of talent. She would bow out for keeps after This Is The Army in 1943, and shunned interviews for decades thereafter. When Barrymore biographers approached her in the late seventies, Dolores was finally ready to talk, but no one seemed interested in her own career, other than Kevin Brownlow, whose Hollywood series captured the first and only on-camera appearance she’d make during the retirement years. Uncharitable observers said she looked like an old Irish washerwoman, which begs the question as to how many of us have had any actual exposure to old Irish washerwomen. If nothing else, she seems to have assumed mother Mae's role as stern family matriarch, and much of her old age was spent trying to extricate Barrymore children and grandchildren from various compromising situations. The lavish scrapbooks of her life with John Barrymore eventually saw publication in a recent oversized book celebrating the first family of acting, and it’s available HERE. Dolores died in 1979 at the age of seventy-five.

Photo CaptionsWarner studio portraitParticipating in a beauty contest with sister HeleneWith John Barrymore in The Sea BeastWith Warner Oland in Old San FranciscoMontage of Warner Bros. rolesHoneymooning with John BarrymoreExhibitor Manual page on DoloresWith husband John BarrymoreTrade Ad promises a "new voice" for DoloresOne Sheet --- Expensive WomenWith Freddie Bartholomew in Little Lord FauntleroyWith Tim Holt in The Magnificent Ambersons