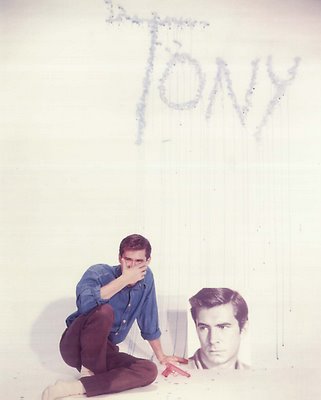

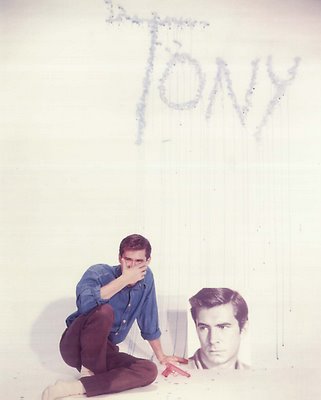

How Are We Supposed To Read This Pose?I suspect Tony Perkins sat for this still a few months before Psycho was released. It was supposidly done at Paramount, and in 1960, so maybe it was part of the campaign for the Hitchcock film. If you looked at this image prior to Psycho’s release, you might think it was cute --- just another instance of a young star having fun with the conventions of Hollywood fan photography. If you came upon it in the Fall of 1960, after that never-to-be-forgotten summer of Psycho, your reading would have been very different. The only thing this picture needs is red paint instead of the gray. Otherwise, it’s Norman --- or better yet, Perkins as we would always think of him after that fateful role forever wiped out any possibility that he’d continue as a popular romantic lead. Tony’s even got his hand covering his face as though he’d just walked into that Bates Motel bathroom after Mother’s visit. The stark white background evokes memories of that little cell they’ve put him in at the end of Psycho. I think this is one creepy shot. It seems to suggest that Perkins himself is a little nuts. Was that the idea? Surely not. Actually, I’m not all that sure this was done for Psycho. It looks more like something Warners might have sanctioned for Tall Story, which was released a few months prior to the Hitchcock film, and featured Tony in one of his gawky, gulping boy parts (there’d be no more of those!). Either way, it sends out a very different message, for me at least, than the one that was no doubt intended.

How Are We Supposed To Read This Pose?I suspect Tony Perkins sat for this still a few months before Psycho was released. It was supposidly done at Paramount, and in 1960, so maybe it was part of the campaign for the Hitchcock film. If you looked at this image prior to Psycho’s release, you might think it was cute --- just another instance of a young star having fun with the conventions of Hollywood fan photography. If you came upon it in the Fall of 1960, after that never-to-be-forgotten summer of Psycho, your reading would have been very different. The only thing this picture needs is red paint instead of the gray. Otherwise, it’s Norman --- or better yet, Perkins as we would always think of him after that fateful role forever wiped out any possibility that he’d continue as a popular romantic lead. Tony’s even got his hand covering his face as though he’d just walked into that Bates Motel bathroom after Mother’s visit. The stark white background evokes memories of that little cell they’ve put him in at the end of Psycho. I think this is one creepy shot. It seems to suggest that Perkins himself is a little nuts. Was that the idea? Surely not. Actually, I’m not all that sure this was done for Psycho. It looks more like something Warners might have sanctioned for Tall Story, which was released a few months prior to the Hitchcock film, and featured Tony in one of his gawky, gulping boy parts (there’d be no more of those!). Either way, it sends out a very different message, for me at least, than the one that was no doubt intended.

Chaplin's Gold Rush Revival Of 1942

Chaplin's Gold Rush Revival Of 1942 There were Chaplin films that generated controversy when they were new. Monsieur Verdoux was pilloried by critics and ignored by the public in 1947, only to be embraced by audiences when revived briefly in 1964. All the Chaplin features would be re-issued successfully in the wake of his Academy Award presentation in 1972, and they’ve remained in popular circulation since. The one most likely to stir debate today is The Gold Rush, and that’s been a fairly recent phenomenon. It's the sole Chaplin feature that exists in two distinctly different versions (several of his silents were amended for re-issues, such as The Kid and The Circus, but only the recut versions are generally available now). The Gold Rush was released in 1925 to a triumphant boxoffice ($2.2 million in domestic rentals toward a worldwide $4.380), and was regarded as Chaplin’s masterpiece, an opinion with which he concurred. After the triumph of The Great Dictator ($5.0 million worldwide), the comedian mounted his first revival of a silent Chaplin film since the beginning of the talkie era. Others had circulated some of the short comedies with new soundtracks, but this would be a major feature re-issue under Chaplin’s own imprinteur, and since he owned the negative outright, he was free to make whatever adjustments to The Gold Rush he saw fit …

There were Chaplin films that generated controversy when they were new. Monsieur Verdoux was pilloried by critics and ignored by the public in 1947, only to be embraced by audiences when revived briefly in 1964. All the Chaplin features would be re-issued successfully in the wake of his Academy Award presentation in 1972, and they’ve remained in popular circulation since. The one most likely to stir debate today is The Gold Rush, and that’s been a fairly recent phenomenon. It's the sole Chaplin feature that exists in two distinctly different versions (several of his silents were amended for re-issues, such as The Kid and The Circus, but only the recut versions are generally available now). The Gold Rush was released in 1925 to a triumphant boxoffice ($2.2 million in domestic rentals toward a worldwide $4.380), and was regarded as Chaplin’s masterpiece, an opinion with which he concurred. After the triumph of The Great Dictator ($5.0 million worldwide), the comedian mounted his first revival of a silent Chaplin film since the beginning of the talkie era. Others had circulated some of the short comedies with new soundtracks, but this would be a major feature re-issue under Chaplin’s own imprinteur, and since he owned the negative outright, he was free to make whatever adjustments to The Gold Rush he saw fit …

In a 1942 world of brash comedy and rat-a-tat verbal sparring (thanks as much to radio as movies), Charlie Chaplin had to be apprehensive over the welcome, or lack of one, he might receive for a seventeen-year old silent movie. There were but a few of these back in circulation over the last ten years. Three had been Rudolph Valentino starrers (The Sheik, Son Of The Sheik, and The Eagle) and one had brought back William S. Hart for a final prologue bow before the camera (Tumbleweeds). Most were handled by independent distributors as novelty shows --- curios for the amusement of women who’d once swooned over Rudy and kids who wondered what all the excitement had been about. Otherwise, silent films were buried deep, and none of the majors had any interest in them beyond scattered art house showings and an occasional print donated to the Museum Of Modern Art. Perhaps it was this uncertainty that inspired Chaplin to modernize The Gold Rush thusly --- Told To The Strains Of Music That Will Tug At Your Heart, Told Through Words That Will Convulse You With Laughter. Charlie’s own pocketbook was convulsed to the tune of $154,000 for the modernization, which included a new score composed by him, and spoken narration he elected to deliver in his own voice. United Artists would distribute on 60-40 terms for all exhibitors, "just like any other UA picture." The preview at Westwood’s Village Theatre was rapturous --- its close proximity to UCLA would bring an appreciative college-age audience. Chaplin himself appeared for the opening, along with an array of major industry names (here he is greeting Mickey Rooney) --- even Mary Pickford showed up with husband Buddy Rogers to launch the new Gold Rush. She, like Chaplin, still maintained an ownership interest in United Artists.

Critical reaction was overwhelmingly positive. James Agee placed it among the year's best films. No one seems to have kicked about that narration or the removal of intertitles. They probably felt, like Chaplin, that a little minor surgery would be needed to make this old film palatable for modern viewers. The idea of narration was not new. Paramount had released some short subjects made up of silent highlights which included an explanatory track, and Metro dished up old footage now and again for their comedic one-reelers. For better or worse, such were templates Chaplin had to go by, and his attempts to augment sight gags with verbal humor in The Gold Rush may well have been inspired by the likes of Pete Smith (perish any thought of that --- I find those things almost unbearable to watch). We may deplore Chaplin’s judgment today, but our hindsight pales before Charlie’s foresight, as his trip down memory lane took a lot of movie-goers with it (New York’s Globe Theatre played all-night on Saturdays to accommodate crowds). We can appreciate The Gold Rush today, not as a product of the silent era, but as a sampling of one great silent comedian trying to adapt his work to fulfill the expectations of a forties audience, and, as it turned out, succeeding very nicely. UA demonstrated its confidence with an all-out campaign. No silent movie revival had gotten this kind of push before. Note the powerhouse panel of 1942 comics paying laughing tribute to the master for a trade ad (and how about that Abbott and Costello telegram endorsement!). The Gold Rush re-issue ended up with $614,000 worldwide, an exceptional number for any oldie, let alone one without dialogue.

So just what’s it like to watch (and hear) Charlie Chaplin in the 1942 Gold Rush today? Nine out of ten fans would give its narrator the hook. Perhaps C.C. anticipated all those DVD audio commentaries we’d someday be assaulted by, and decided to get in his licks sixty-five years early. If you like sitting beside someone at the movies who will explain what you’re watching, while you’re watching it, then this is the Gold Rush for you. Otherwise, I’d recommend the original 1925 silent version, recently reconstructed by Kevin Brownlow and available on a Warners double-disc (with the 1942 edition). Your preference will probably depend on which you saw first. For me, it was an 8mm print of the original I got back in 1969, mounted on nine little reels, and dead mute other than classical recordings I played along with it. I am, therefore, an adherent of the 1925 version. On the other hand, there are Chaplin fans who will go to the mat for his re-issue, having seen it at an impressionable age and falling in love with it thus. It’s fortunate we can choose. The ideal would be to somehow marry the picture quality from 1942 --- with silent titles from 1925 --- to the Chaplin music from 1942, but without the Chaplin voice of 1942, and then stand back and shout, It’s Alive … Alive! Until that happy (but unlikely) day, we must make our election based on what’s available, and thankfully, both versions are.

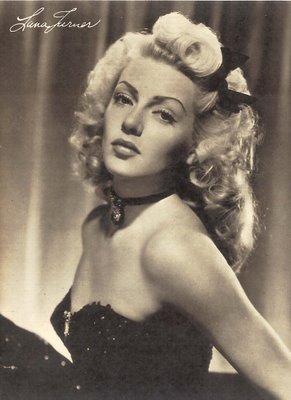

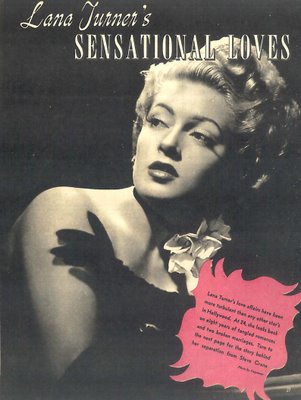

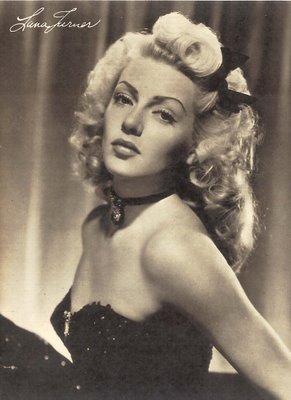

Lana-Thon Today

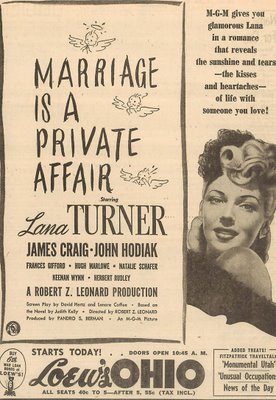

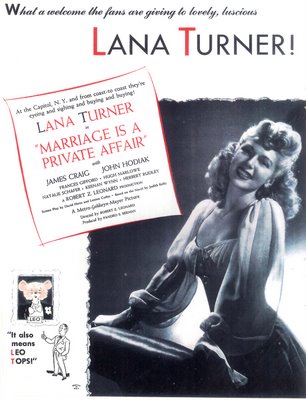

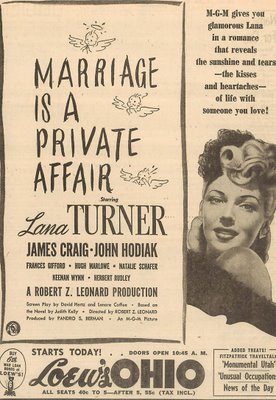

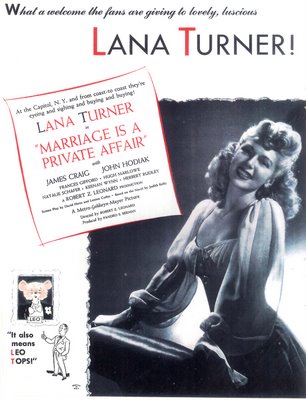

Lana-Thon Today Lana-Thon headquarters is over at Flickhead (HERE), and Ray has links to participating webpages, so by all means check that out. In the meantime --- what’s to say about Lana Turner? Unless you’re a fan, and their numbers aren’t likely to be on the increase, she may come across as a less energized Marilyn Monroe --- or a latter-day de-clawed would-be Harlow sex kitten reigned in by the Code. Then why write about her? I can’t offer a definitive answer because I was born too late. Most of us were. The ones who could tell us all about Lana Turner and what she meant to her once wildly enthusiastic fan base are a dwindling lot of world war veterans --- the men who served and worshipped Lana, and the women who crowded her movies stateside and lived vicariously through her romances, both onscreen and off. It’s easy for our generation to regard her as a studio manufactured joke, for we never experienced the anxieties that a star like Lana was there to alleviate. She was comfort food with a brief shelf life, but like strawberries fresh from the market, she had an intoxicating flavor that just can’t be experienced so many years after the initial purchase, and a movie like Marriage Is A Private Affair can give but the barest hint of what it must have been like to taste Lana in her prime. She would certainly make better pictures (The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Bad and The Beautiful, Imitation Of Life), but none that summon up her essential appeal like this one. That it’s so utterly forgotten today is no doubt due to the fact that Marriage Is A Private Affair exists purely as a Lana Turner vehicle, 116 minutes to luxuriate in her presence --- not enough for us, but plenty for moviegoers in 1944.

Lana-Thon headquarters is over at Flickhead (HERE), and Ray has links to participating webpages, so by all means check that out. In the meantime --- what’s to say about Lana Turner? Unless you’re a fan, and their numbers aren’t likely to be on the increase, she may come across as a less energized Marilyn Monroe --- or a latter-day de-clawed would-be Harlow sex kitten reigned in by the Code. Then why write about her? I can’t offer a definitive answer because I was born too late. Most of us were. The ones who could tell us all about Lana Turner and what she meant to her once wildly enthusiastic fan base are a dwindling lot of world war veterans --- the men who served and worshipped Lana, and the women who crowded her movies stateside and lived vicariously through her romances, both onscreen and off. It’s easy for our generation to regard her as a studio manufactured joke, for we never experienced the anxieties that a star like Lana was there to alleviate. She was comfort food with a brief shelf life, but like strawberries fresh from the market, she had an intoxicating flavor that just can’t be experienced so many years after the initial purchase, and a movie like Marriage Is A Private Affair can give but the barest hint of what it must have been like to taste Lana in her prime. She would certainly make better pictures (The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Bad and The Beautiful, Imitation Of Life), but none that summon up her essential appeal like this one. That it’s so utterly forgotten today is no doubt due to the fact that Marriage Is A Private Affair exists purely as a Lana Turner vehicle, 116 minutes to luxuriate in her presence --- not enough for us, but plenty for moviegoers in 1944.

In case you haven’t seen it on TCM, here’s the set-up. Lana’s a party girl with money who marries serviceman John Hodiak. Complications ensue. That’s pretty much it. The movie opens with an outsized wedding sequence that must have set many a second-shift Lockheed girl’s heart a-flutter, and the extended honeymoon idyll, which seems destined to run into 1945, provides the sort of vicarious you-are-there sensation that all movies strive for, and seldom attain. This is where we really have to admire the efficiency of the Dream Factory. That wedding night, staged as it was on the most patently artificial stage since Random Harvest, fulfilled the wartime yearnings of both sexes. Men in uniform could substitute themselves for John Hodiak (no problem there, since Hodiak was anything but an imposing presence, and even the lowliest G.I. could imagine supplanting him), while women could anticipate a future that might include a romantic wedding trip where money is seemingly no object and no one has to worry about getting back to work. Reality never intrudes upon Lana’s world. That all seems dated and foolish to us now, but it was more than satisfying then. Marriage Is A Private Affair premiered with 98 prints on military camps and bases in September 1944. Lana Turner appeared with the show in Naples, Italy, and provided a filmed prologue in which she greeted soldier audiences from the screen and delivered a "chin-up" message. This was her first picture in eleven months (maternity leave) and the anticipation was intense. Marriage Is A Private Affair went on to deliver $1.9 million in domestic rentals against a negative cost of $1.5, with $715,000 in foreign rentals. The final profit was $237,000.

I’m told that Marriage Is A Private Affair was Tennessee William’s first Hollywood writing assignment. He contributed some dialogue. Actually, the writing isn’t so bad. A best selling novel was credited as the source, but the Breen Office had forced a near-total abandonment of that, being as how it dealt rather explicitly with adultery and featured an abortion among the key plot devices. Books like these were as disposable then as they are forgotten now, and yet I did find multiple copies of the novel for sale at AbeBooks on line, so a lot of them must be turning up in attics and estate auctions (it was also serialized in Ladies Home Journal). Is there anything so discredited today as a movie adaptation of a best-selling novel that no one remembers? One noteworthy thing about Marriage Is A Private Affair is the supporting cast. This was the first time Lana Turner had carried a picture on her own --- before, there had been at least one co-star of equal stature --- but this time, she’s backed up by an interesting group of young contract hopefuls, and that in itself makes this picture well worth seeing. James Craig is Hodiak’s rival for her affections. He’s mustachioed and smirked out as if doubling for now-in-the-service Clark Gable. It’s one of the most slavishly imitative performances you’re ever likely to see. Tom Drake has one big scene where he plays the ghost of a downed flyer who’d been Lana’s sweetheart. This may have been the audition, and it’s a nice one, that got Drake the Meet Me In St. Louis part. Frances Gifford never seems to have gotten the breaks, at MGM or elsewhere, but she’s awfully good here in what’s easily the most interesting part in the picture. Herbert Rudley never scaled the heights either, but I always liked him (there’s a nice chat with Rudley in one of Tom Weaver’s terrific interview books).

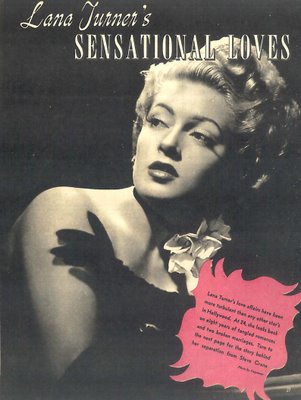

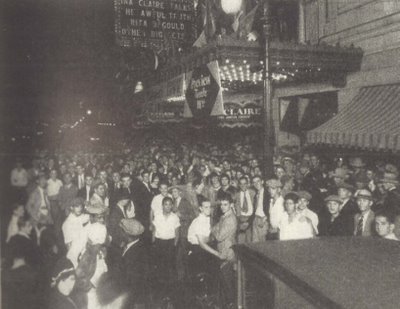

Check out Lana Turner’s Sensational Loves. This article was published in tandem with the release of Marriage Is A Private Affair. Here was another instance of a star’s personal life serving the interests of the product. Even the title promises an insider’s peek at Lana’s marital wreckage. The "Welcome Back" trade ad refers to that absence of almost a year, and the fan frenzy that greeted her return (the crowd in front of the theatre was typical during that era when movies really had a mass audience). Note the twin bed in this shot with John Hodiak --- that was the one sticking point with audiences during those military base premieres, for even during the honeymoon, Lana and Hodiak occupied separate beds. The whistles and catcalls in response to these Code-dictated accommodations were said to have been deafening. Marriage Is A Private Affair was truly an instance of a movie that could only work, and did work, at a particular moment in time. There were many such pictures coming out of the studios then, particularly during the war (and it seems the lion’s share were from Metro). They may not survive as popular entertainment for a general audience, but for fans like us, they’re fascinating time capsules, and this is one Lana Turner obscurity that’s well worth catching next time it’s on TCM.

Some Super Books On Vintage HollywoodMark A.Vieira has written a number of books about vintage Hollywood. He’s also a professional photographer whose mentors included the great George Hurrell, who would himself become the subject of a beautiful Vieira coffee table volume. Mark’s books contain the most incredible still reproduction I’ve ever seen in print. His practiced eye for all things photographic has yielded some of the most stunning collections you’re ever likely to see. I’ve been reviewing two of his more recent ones this week, Greta Garbo: A Cinematic Legacy and Hollywood Horror. Having read both when first published, I found myself immersed in the text once again --- Vieira makes with some of the best film writing around --- and all that behind-the-scenes stuff he reveals is just not to be seen (or read) elsewhere. The photos in both books are super rare (here are two of them). Mark’s been a collector long enough to know what’s already been published, and avoids much of that. In all my years of perusing monster mags and horror books, I thought I’d seen everything, but these images from classic shockers really blew me away. His Starlight Studio website has a page devoted to each of his books --- Garbo is HERE, and Hollywood Horrors HERE (there’s a fascinating story at the site about Mark’s own personal ordeal in writing the latter), along with ordering info. If I could but rescue a handful of books from a burning house (God forbid such a thing), Mark Vieira’s would be the first ones I’d grab …

Some Super Books On Vintage HollywoodMark A.Vieira has written a number of books about vintage Hollywood. He’s also a professional photographer whose mentors included the great George Hurrell, who would himself become the subject of a beautiful Vieira coffee table volume. Mark’s books contain the most incredible still reproduction I’ve ever seen in print. His practiced eye for all things photographic has yielded some of the most stunning collections you’re ever likely to see. I’ve been reviewing two of his more recent ones this week, Greta Garbo: A Cinematic Legacy and Hollywood Horror. Having read both when first published, I found myself immersed in the text once again --- Vieira makes with some of the best film writing around --- and all that behind-the-scenes stuff he reveals is just not to be seen (or read) elsewhere. The photos in both books are super rare (here are two of them). Mark’s been a collector long enough to know what’s already been published, and avoids much of that. In all my years of perusing monster mags and horror books, I thought I’d seen everything, but these images from classic shockers really blew me away. His Starlight Studio website has a page devoted to each of his books --- Garbo is HERE, and Hollywood Horrors HERE (there’s a fascinating story at the site about Mark’s own personal ordeal in writing the latter), along with ordering info. If I could but rescue a handful of books from a burning house (God forbid such a thing), Mark Vieira’s would be the first ones I’d grab …

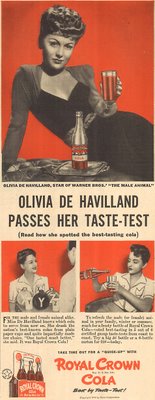

Olivia DeHavilland --- Part TwoSo just what was at stake when Olivia sued Warners to get out of her seven-year (and counting) contract? Well, as it turns out, just six months. That’s how much they’d tacked on after figuring in her suspentions, lost production time, etc. That means she ended up losing nearly three years of screen time for the sake of one sixth that. She stood on principle and won, but was it worth the struggle? Her legal fees must have been astronomical. Warners sent out a letter that effectively blacklisted her during the pendency of the trial, and other than a few radio gigs, she had to idle out all that time with no assurance her public would be waiting at the finish. I’ve got to say this was one gutsy woman. They named the new law after her, and she’s justifiably proud of it to this day. If you took away all Olivia’s movies, she’d still be a noteworthy personage just for this --- the first person to take on the Hollywood slavemasters and win.

Olivia DeHavilland --- Part TwoSo just what was at stake when Olivia sued Warners to get out of her seven-year (and counting) contract? Well, as it turns out, just six months. That’s how much they’d tacked on after figuring in her suspentions, lost production time, etc. That means she ended up losing nearly three years of screen time for the sake of one sixth that. She stood on principle and won, but was it worth the struggle? Her legal fees must have been astronomical. Warners sent out a letter that effectively blacklisted her during the pendency of the trial, and other than a few radio gigs, she had to idle out all that time with no assurance her public would be waiting at the finish. I’ve got to say this was one gutsy woman. They named the new law after her, and she’s justifiably proud of it to this day. If you took away all Olivia’s movies, she’d still be a noteworthy personage just for this --- the first person to take on the Hollywood slavemasters and win.

Two academy awards within four years must have looked like a sure-fire insurance policy against unemployment, but as things turned out, The Heiress would be both her summit and finish. There just aren’t any outstanding Olivia DeHavilland pictures after that --- at least none that revolve around her. Bette Davis experienced the same thing, and around the same time, with All About Eve. You’re at the top, but there’s younger faces beating at the door, and those increasingly wizened leading men (Flynn, Gable, Cooper, etc.), not to mention post-war starters of the Mitchum, Lancaster, and Kirk Douglas variety, are leaning toward fresher faces for the sake of their own appearance of youth. How it must have rankled to see Grace Kelly, Audrey Hepburn and all the rest scooping up the plum roles Olivia could have more than played. Her own determination to have something of a normal offscreen life does at least partly explain it. DeHavilland’s list of priorities never found movies at the top. Unlike Bette Davis, she never clutched at the work, and bad pictures of the sort Bette embraced were more or less avoided. Grocers like to be paid, however, and that no doubt explains her participation in The Swarm and various TV movies that came later. You gotta hand it to Olivia for still having the juice to play bed scenes as late as 1970 in The Adventurers (not quite as loathsome a picture as its reputation would indicate), and to this day, she makes no apologies for Lady In The Cage, one of the meanest thrillers the sixties ever produced.

Two academy awards within four years must have looked like a sure-fire insurance policy against unemployment, but as things turned out, The Heiress would be both her summit and finish. There just aren’t any outstanding Olivia DeHavilland pictures after that --- at least none that revolve around her. Bette Davis experienced the same thing, and around the same time, with All About Eve. You’re at the top, but there’s younger faces beating at the door, and those increasingly wizened leading men (Flynn, Gable, Cooper, etc.), not to mention post-war starters of the Mitchum, Lancaster, and Kirk Douglas variety, are leaning toward fresher faces for the sake of their own appearance of youth. How it must have rankled to see Grace Kelly, Audrey Hepburn and all the rest scooping up the plum roles Olivia could have more than played. Her own determination to have something of a normal offscreen life does at least partly explain it. DeHavilland’s list of priorities never found movies at the top. Unlike Bette Davis, she never clutched at the work, and bad pictures of the sort Bette embraced were more or less avoided. Grocers like to be paid, however, and that no doubt explains her participation in The Swarm and various TV movies that came later. You gotta hand it to Olivia for still having the juice to play bed scenes as late as 1970 in The Adventurers (not quite as loathsome a picture as its reputation would indicate), and to this day, she makes no apologies for Lady In The Cage, one of the meanest thrillers the sixties ever produced.

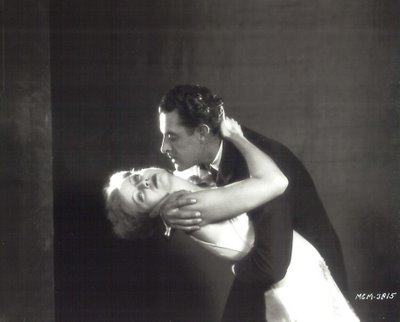

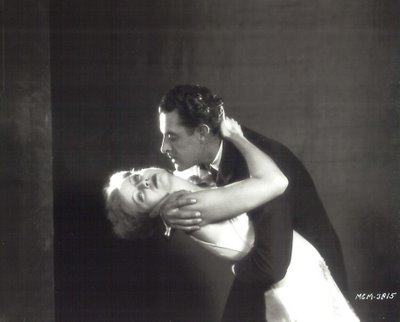

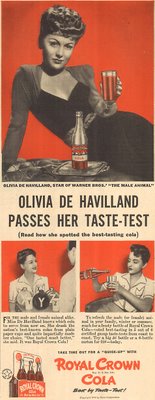

Just a comment or two about yesterday’s images. Anybody like to take a guess at what was going through Leslie Howard’s mind when he posed for that 1937 shot with delectable Olivia? Bet she could throw down some ribald anecdotes about him, as Les was without peer among Hollywood seducers --- something tells me he missed the boat with Olivia, however --- though you just know he tried. Same goes for Fredric March (from Anthony Adverse) --- his methods were more direct, I understand, but honestly, when you’re confronted with Olivia at age 19, you can hardly blame the poor man for trying. A commenter from Part One noticed that unretouched shot and wondered if Olivia might have partied to excess the night before --- I say probably not --- a few of those Warner workdays and I’d probably look like Eddie Robinson at the end of Scarlet Street. As for today’s pics, I like this one of director Raoul Walsh conferring with Errol and Olivia during They Died With Their Boots On --- I always bust out crying during that last scene they do together. RC Cola sure got around in those days --- it’s been forty years since I tried one --- maybe it’s time to take another flyer on that sparkling beverage, this time on Olivia’s recommendation.

Just a comment or two about yesterday’s images. Anybody like to take a guess at what was going through Leslie Howard’s mind when he posed for that 1937 shot with delectable Olivia? Bet she could throw down some ribald anecdotes about him, as Les was without peer among Hollywood seducers --- something tells me he missed the boat with Olivia, however --- though you just know he tried. Same goes for Fredric March (from Anthony Adverse) --- his methods were more direct, I understand, but honestly, when you’re confronted with Olivia at age 19, you can hardly blame the poor man for trying. A commenter from Part One noticed that unretouched shot and wondered if Olivia might have partied to excess the night before --- I say probably not --- a few of those Warner workdays and I’d probably look like Eddie Robinson at the end of Scarlet Street. As for today’s pics, I like this one of director Raoul Walsh conferring with Errol and Olivia during They Died With Their Boots On --- I always bust out crying during that last scene they do together. RC Cola sure got around in those days --- it’s been forty years since I tried one --- maybe it’s time to take another flyer on that sparkling beverage, this time on Olivia’s recommendation.

Stars always looked bored doing radio shows. It’s just reading dialogue, after all, with commercial breaks at that. I understand a lot of screen names dreaded that microphone --- never could get used to the format. Sunday rotogravures are irresistible here at the Greenbriar, mainly because few of them seem to get published elsewhere, so they’re always a kick to run across. Here’s two that Olivia did during the early forties. Maybe I should watch The Snake Pit someday, but I’m still a little afraid of it. I’d rather see our girl smooching with Errol than flailing around an asylum --- anyway, here she is with Mark Stevens. The Heiress was one of the first adult movies I watched and really enjoyed at age fourteen. I thought it then and think it now --- you just can’t make an ugly duckling out of this woman --- and besides that, I think she made a mistake turning the lock on Monty at the end. You know it’s the last chance she’s ever going to get with a man (judging by that sour attitude she’s developed), and it always seemed to me that the guy loved her well enough --- he just didn’t want to have to go out and work for a living. As long as money and lifestyle were part of the package, Morris would have made a great husband, especially with that hateful old Daddy out of the way. One of my favorite pictures ever made, and I keep hoping each time that somehow she’ll surprise me and go running back down those stairs at the end --- but it never happens. Finally, there’s Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte. Some of us went straight from school one afternoon in 1965 to see that one. We got into the auditorium a few minutes after it started, and the first thing I saw was Bruce Dern getting his hand chopped off. That, plus a Baby Ruth, was sheer nirvana for me. I knew I'd come to the right place. Definitely time to watch this one again. Always love seeing Olivia slapping Bette around in that car --- Now will you shut your mouth --- never tire of that deathless line …

Stars always looked bored doing radio shows. It’s just reading dialogue, after all, with commercial breaks at that. I understand a lot of screen names dreaded that microphone --- never could get used to the format. Sunday rotogravures are irresistible here at the Greenbriar, mainly because few of them seem to get published elsewhere, so they’re always a kick to run across. Here’s two that Olivia did during the early forties. Maybe I should watch The Snake Pit someday, but I’m still a little afraid of it. I’d rather see our girl smooching with Errol than flailing around an asylum --- anyway, here she is with Mark Stevens. The Heiress was one of the first adult movies I watched and really enjoyed at age fourteen. I thought it then and think it now --- you just can’t make an ugly duckling out of this woman --- and besides that, I think she made a mistake turning the lock on Monty at the end. You know it’s the last chance she’s ever going to get with a man (judging by that sour attitude she’s developed), and it always seemed to me that the guy loved her well enough --- he just didn’t want to have to go out and work for a living. As long as money and lifestyle were part of the package, Morris would have made a great husband, especially with that hateful old Daddy out of the way. One of my favorite pictures ever made, and I keep hoping each time that somehow she’ll surprise me and go running back down those stairs at the end --- but it never happens. Finally, there’s Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte. Some of us went straight from school one afternoon in 1965 to see that one. We got into the auditorium a few minutes after it started, and the first thing I saw was Bruce Dern getting his hand chopped off. That, plus a Baby Ruth, was sheer nirvana for me. I knew I'd come to the right place. Definitely time to watch this one again. Always love seeing Olivia slapping Bette around in that car --- Now will you shut your mouth --- never tire of that deathless line …

Monday Glamour Starter --- Olivia De Havilland --- Part OneIt seemed to me that Olivia De Havilland sort of merged with Melanie Hamilton about thirty years ago, hiding behind that persona so as to avoid revealing too much of her real self during all those dreary "nostalgia" oriented interviews. Melanie was a benign and beloved figure. Why not become her? There was a reasonably candid exchange with AFI students in October of 1974, but after that, she went into character and stayed there. More recently, there have been Academy Award appearances and a lengthy account on DVD of the Gone with the Wind filming. Her precise diction is to be admired, but it also creates a distance. Nothing seems spontaneous. Like a lot of elder statesmen, she’s got her line of anecdotes and she’s going to stick to them (a Los Angeles Times profile from just last week found her calling up many of them). It’s got to be tough when you’re nearing ninety to vary the dance card of memories when they go back nearly three quarters of a century. Just showing up should be more than enough, and yet one longs for a really knowledgeable interviewer to sit down with Olivia and get into specifics --- the junkets for Dodge City and Santa Fe Trail --- working with James Whale in The Great Garrick --- hey, what about co-starring with Sonny Tufts? – twice! Too bad access is limited to those same tired MSM outlets, forever dumbing down their puffball questions, wasting what might otherwise be a unique opportunity to get some Hollywood lowdown from one of its last great survivors. I’d like to think there was some livelier Q&A at that recent Academy tribute, but being 3000 miles away, I can’t know for sure. Was anyone there?

Monday Glamour Starter --- Olivia De Havilland --- Part OneIt seemed to me that Olivia De Havilland sort of merged with Melanie Hamilton about thirty years ago, hiding behind that persona so as to avoid revealing too much of her real self during all those dreary "nostalgia" oriented interviews. Melanie was a benign and beloved figure. Why not become her? There was a reasonably candid exchange with AFI students in October of 1974, but after that, she went into character and stayed there. More recently, there have been Academy Award appearances and a lengthy account on DVD of the Gone with the Wind filming. Her precise diction is to be admired, but it also creates a distance. Nothing seems spontaneous. Like a lot of elder statesmen, she’s got her line of anecdotes and she’s going to stick to them (a Los Angeles Times profile from just last week found her calling up many of them). It’s got to be tough when you’re nearing ninety to vary the dance card of memories when they go back nearly three quarters of a century. Just showing up should be more than enough, and yet one longs for a really knowledgeable interviewer to sit down with Olivia and get into specifics --- the junkets for Dodge City and Santa Fe Trail --- working with James Whale in The Great Garrick --- hey, what about co-starring with Sonny Tufts? – twice! Too bad access is limited to those same tired MSM outlets, forever dumbing down their puffball questions, wasting what might otherwise be a unique opportunity to get some Hollywood lowdown from one of its last great survivors. I’d like to think there was some livelier Q&A at that recent Academy tribute, but being 3000 miles away, I can’t know for sure. Was anyone there?

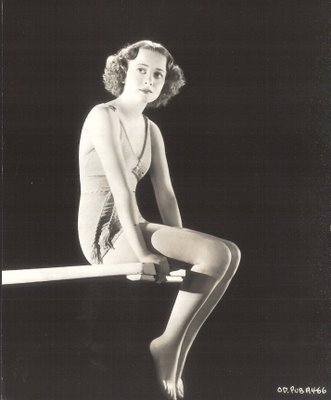

I’m just going to do a blueprint for all these Glamour Starter entries and lay it down each week --- save myself some duplicated effort. Here goes --- strong mother, would-be actress daughter(s), distant and/or weak father, mother seeks separation in order to accommodate daughter’s career aspirations, and so on. The variations this time are as follows --- Dad was actually cool with the separation (he had a Japanese housekeeper girlfriend back home in Tokyo where Olivia was born), the daughters were fiercely competitive, and Olivia wasn’t even sure she wanted to be an actress. That I had not known. She was talked into staying with Max Reinhardt’s Midsummer Night’s Dream troupe after a sensational understudy turn for unavailable star Gloria Stuart. A teacher’s program scholarship at Mills College was eventually forfeited in favor of two-hundred a week at Warner Bros., where she’d debut in the 1935 film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Sister Joan Fontaine (her name taken from a step-father) also started the climb, but prospects at RKO were less promising. For now, it looked as though Olivia would be the star breadwinner. Jack L. saw her as a standard issue ingenue, and look what became of those --- Anita Louise, Jean Muir, Margaret Lindsay --- scarcely names to reckon with outside a TCM marathon. If anything, Olivia was compromised by her looks. She was just too pretty to be taken seriously. Better to let her play insipid leads opposite Joe E. Brown and George Brent that any of the stock girls could have done in their sleep. This might have lasted the entire seven years of her contract, but for the miraculous teaming with Errol Flynn in Captain Blood that would lead to seven more tandem appearances and still thriving multi-generational speculation as to the question of did they or didn’t they? Let’s just say the relationship was a lot more complex than anyone then or now realized. If indeed Olivia has an unfinished memoir, I hope she’ll address the Flynn paradox at length.

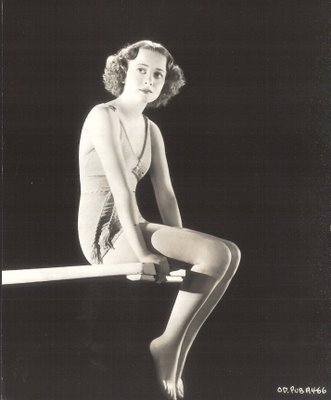

After Gone With The Wind (she’s here with Ona Munson), a part of Olivia De Havilland would forever be bathed in sweetness and light. The memory of Melanie would lend shock value to cast-against-type perfidy she’d display in Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte ("now-will-you-shut-your-mouth?"). After GWTW, we look for Melanie, I mean, Olivia, to drop her halo and join the rest of us fallen angels. There’s a great series of blooper reels Warners used to do each year for the Christmas parties. They weren’t meant for public consumption, and they’re laced with profanity (some are turning up on DVD --- watch for them). One clip finds Olivia blowing a line with Paul Henreid as they’re shooting Devotion. "Son-of-a-bitch!" she exclaims, giving each syllable the benefit of her precise, measured delivery. She really stole my heart with that one. Others on the Warner lot were similarly affected. According to Stuart Jerome’s delightfully ribald, if not downright nasty, reminiscence of his days as a WB messenger boy, Olivia was one dream girl the guys really lusted after. Her virginal image just made the package that much more enticing for those randy teenagers bicycling memos back and forth across the lot. Used copies of Those Crazy, Wonderful Days When We Ran Warner Bros. are available over at Amazon --- right now they’re going for less than two dollars (HERE). I laughed till I cried back in 1983 when it was first published. I don’t really blame J.L. for confining Olivia to ingenue parts. I mean, just look at these swimsuit poses, and that delightful little pirate rig she’s donned to help sell Captain Blood. Even unretouched, as shown here, she’s perfection. All those shrieking murderesses locking unwanted husbands in garages with the car running parts went to Bette Davis and Ida Lupino. How could anyone with a face like the one George Hurrell photographed here for Dodge City resort to things like that? Better to let her remain Errol Flynn’s demure consort, even if it would take decades for the critical establishment (if not Olivia herself) to realize how wonderful those Flynn shows were, and how fortunate she was to have been a part of them. The big contract bust-out that made judicial history (and finally got her off the Warner lot) is something I still have mixed feelings about, but that’ll need to wait for Part 2.

A Sunday Photo MysteryI do not have the answer to this riddle. That is why I’m presenting it to you. All I can do is date the still to 1955. I would really like to know why these people have gathered. Is it the Academy Awards for that year? If so, then why this peculiar seating arrangement? Here are the faces I recognize offhand --- James Cagney and Susan Hayward (standing), front row --- James Stewart, Greer Garson, Gregory Peck, Fredric March, not sure, and Bill Holden. Second row --- Edmond O’ Brien, Paul Douglas, don’t know, no idea, Walt Disney, don’t know, Gene Kelly, not sure (Eva Marie Saint?), Walter Pidgeon, Brod Crawford (Good! Glad they invited Brod). Third row --- I only recognize Billy Wilder, George Stevens, Jack Lemmon, (surely not) Joseph Schenck, Danny Thomas, Walter Wanger. Back row --- James Wong Howe on the left, I’m pretty sure, and Martin Scorsese (some funny joke, huh?). These other guys must be producers and/or executives…. Academy officers maybe? A once-in-a-lifetime gathering, in any event.

A Sunday Photo MysteryI do not have the answer to this riddle. That is why I’m presenting it to you. All I can do is date the still to 1955. I would really like to know why these people have gathered. Is it the Academy Awards for that year? If so, then why this peculiar seating arrangement? Here are the faces I recognize offhand --- James Cagney and Susan Hayward (standing), front row --- James Stewart, Greer Garson, Gregory Peck, Fredric March, not sure, and Bill Holden. Second row --- Edmond O’ Brien, Paul Douglas, don’t know, no idea, Walt Disney, don’t know, Gene Kelly, not sure (Eva Marie Saint?), Walter Pidgeon, Brod Crawford (Good! Glad they invited Brod). Third row --- I only recognize Billy Wilder, George Stevens, Jack Lemmon, (surely not) Joseph Schenck, Danny Thomas, Walter Wanger. Back row --- James Wong Howe on the left, I’m pretty sure, and Martin Scorsese (some funny joke, huh?). These other guys must be producers and/or executives…. Academy officers maybe? A once-in-a-lifetime gathering, in any event.

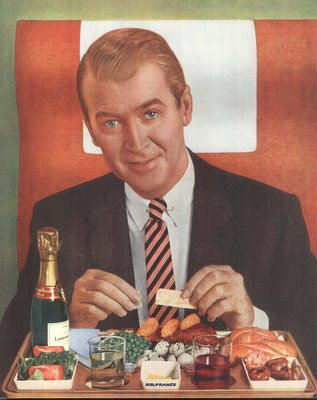

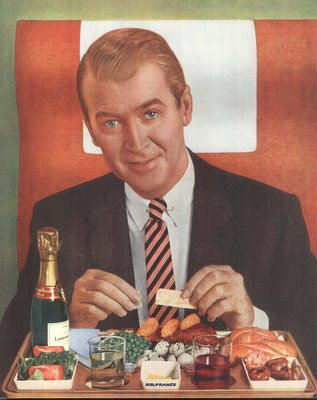

Not Like The Last Time I FlewOh, for the glamour of air travel so long ago as here. Observe the tie-in MGM has arranged with American Airlines for their 1951 comedy, Three Guys Named Mike. Flying was fun back then. At least that’s the way American and Air-France sold it. Also luxurious and comfortable. Look at that feast Jim’s sat down to! Nowadays you’re lucky to score a bag of peanuts on a continental flight. And yet another reminder of how guys dressed back then. Van and Jim knew how. That is fried chicken with the green peas and potatoes, isn’t it? I was born too late. If flying were anything like this today, maybe I’d have gone out to L.A. for that Academy tribute they just had for Olivia DeHavilland. As it is, I’ll have to settle for her as Glamour Starter this coming week. She turns 90 on July 1. Right now, she’s out there giving interviews. Hope when they fly her back home to France they’ll give her a meal as good as the one Jim’s eating, but if I were Olivia, I wouldn’t count on it.

Not Like The Last Time I FlewOh, for the glamour of air travel so long ago as here. Observe the tie-in MGM has arranged with American Airlines for their 1951 comedy, Three Guys Named Mike. Flying was fun back then. At least that’s the way American and Air-France sold it. Also luxurious and comfortable. Look at that feast Jim’s sat down to! Nowadays you’re lucky to score a bag of peanuts on a continental flight. And yet another reminder of how guys dressed back then. Van and Jim knew how. That is fried chicken with the green peas and potatoes, isn’t it? I was born too late. If flying were anything like this today, maybe I’d have gone out to L.A. for that Academy tribute they just had for Olivia DeHavilland. As it is, I’ll have to settle for her as Glamour Starter this coming week. She turns 90 on July 1. Right now, she’s out there giving interviews. Hope when they fly her back home to France they’ll give her a meal as good as the one Jim’s eating, but if I were Olivia, I wouldn’t count on it.

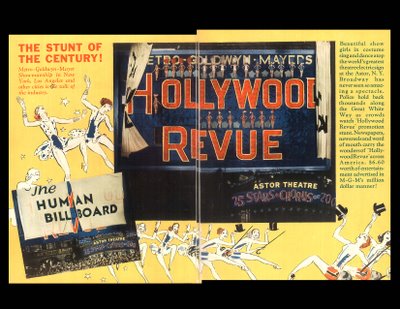

Are Human Billboards Necessary?

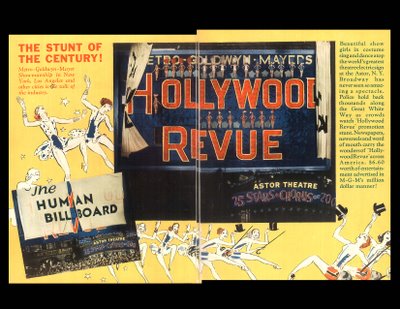

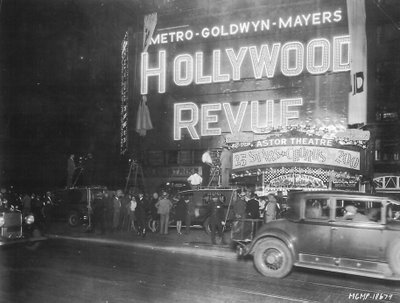

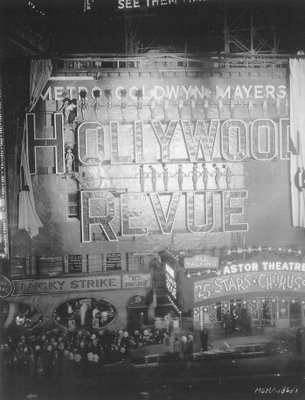

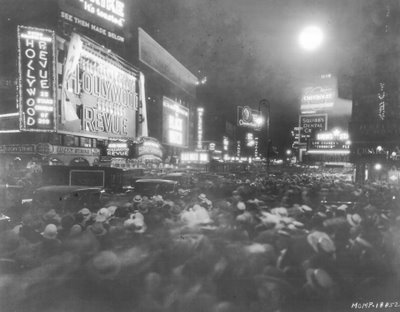

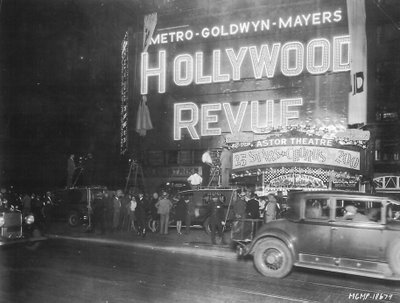

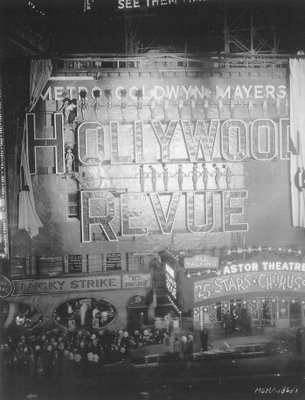

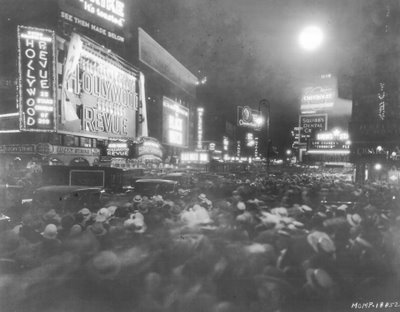

Are Human Billboards Necessary? One can only assume that human life was cheap back in 1929, or maybe they saw the big Crash coming and just said to hell with it all, because suddenly, and for a brief shining moment, those Broadway marquees lit up with some of the most bizarre and extravagant bally stunts in the history of showmanship. Trade observers gave MGM credit for the first "Human Billboard" --- shown here at the Astor Theatre’s opening for The Hollywood Revue Of 1929. Those showgirls were obliged to pose for hours atop the individual letters of an enormous electric sign as it faced out onto a nightly mob of spectators. Never mind the risk of electrocution. What if they’d fallen? Those were narrow catwalks as you can see, and blinding searchlights wouldn’t enhance anyone’s equilibrium. What a way to make a living! The far shot gives you an idea of what Broadway had to offer on this particular evening --- click and enlarge to see those marquees for The Black Watch (John Ford’s first talking feature) and Lon Chaney’s final silent film, Thunder. There’s no record of any of those girls having tumbled from their perch, though we all would within a few weeks when Wall Street laid its egg.

One can only assume that human life was cheap back in 1929, or maybe they saw the big Crash coming and just said to hell with it all, because suddenly, and for a brief shining moment, those Broadway marquees lit up with some of the most bizarre and extravagant bally stunts in the history of showmanship. Trade observers gave MGM credit for the first "Human Billboard" --- shown here at the Astor Theatre’s opening for The Hollywood Revue Of 1929. Those showgirls were obliged to pose for hours atop the individual letters of an enormous electric sign as it faced out onto a nightly mob of spectators. Never mind the risk of electrocution. What if they’d fallen? Those were narrow catwalks as you can see, and blinding searchlights wouldn’t enhance anyone’s equilibrium. What a way to make a living! The far shot gives you an idea of what Broadway had to offer on this particular evening --- click and enlarge to see those marquees for The Black Watch (John Ford’s first talking feature) and Lon Chaney’s final silent film, Thunder. There’s no record of any of those girls having tumbled from their perch, though we all would within a few weeks when Wall Street laid its egg.

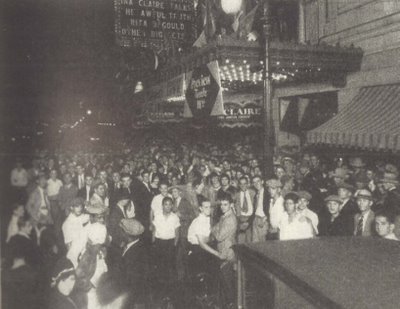

Others would emulate the Hollywood Revue stunt. Cleveland banned the human billboard when Metro tried to erect it there, citing city code violations. The local fire department was instructed to turn their hoses on the girls should they venture out onto the sign (poor things would have lighted up like Man-Made Monster’s Dan McCormick in that event!), while members of the constabulary stood by to arrest theatre staff members tempted to activate power. By the time the picture finally opened, controversy had stirred up sufficient press as to guarantee four thousand turnaways every day at the boxoffice. Metro’s mission was accomplished. A few weeks later, Fox went with a "Living Sign" for its Dallas, Texas engagement of The Cockeyed World. This time the billboard (shown above) was located two blocks from the Majestic Theatre where the show was playing. Buglers standing on the sign would sound off at regular intervals to be answered by more buglers stationed over the marquee back at the Majestic. Thirteen boys in Marine uniforms stood on the elevated billboard, accompanied by a thirty piece military band that played constantly. All this was to lead up to the midnight premiere of The Cockeyed World, but no one anticipated the teeming mass of humanity that would clog streets on opening night (that's them above). Lines for the show extended two blocks in as many directions. People were pushed against store windows and they broke. Streetcars were immobile. Women fainted. It was a great night at the movies in Dallas.

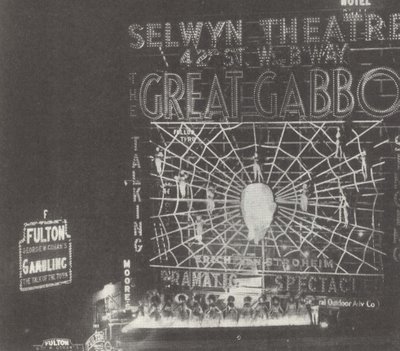

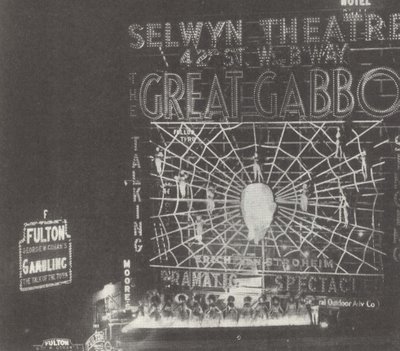

New York cops had a snoot-full of human billboards by the time The Great Gabbo blew into town in early October 1929, and now they were going to do something about it. A proposed court order alleged blockage of street traffic and needless congestion among pedestrians. Indeed, this bally was labeled "the first complete free show ever held on a Broadway roof to advertise a screen spectacle" --- a $12,000 structure featuring twenty showgirls dangling from an electrified spider’s web, while ten ballet dancers performed along the edge of the roof. As the still at left illustrates, all this took place 150 feet above street level. The presiding judge was persuaded by Gabbo producers to check out the billboard action for himself. Following a twenty-five minute view from an elevated vantage point opposite the sign, His Honor ruled in favor of the bally merchants and forbade further interference with their campaign, saying that "Broadway has become famous for its gargantuan display of mazda signs and that these electrical advertisements help to draw tourists to the thoroughfare from all parts of the world." Little did he realize that much of this was about to end, as that initial boom year for early talkies would soon be eclipsed by a stark downturn that would come with the Great Depression.