skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Our Gang --- Part Two

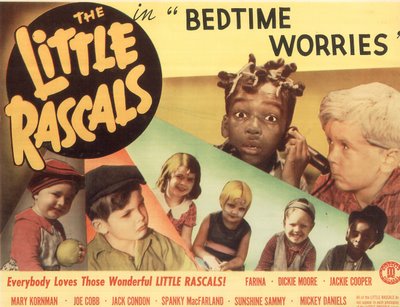

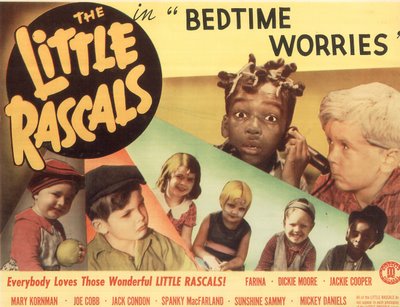

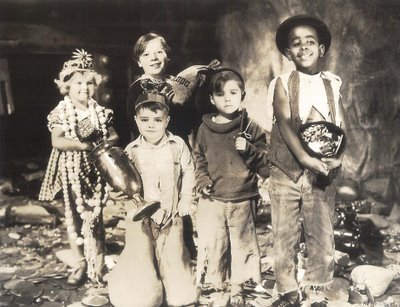

Our Gang --- Part Two By 1935, they’d honed off rougher edges and promoted the Rascals to a level of comfort and stability denied their early talkie brethren. Much of what would eventually undermine the series at MGM began here. Our Gang now ran lemonade stands and put on impromptu shows. Spanky was fussed over by Hattie McDaniel as uniformed domestic in a distinctly middle-class home (Anniversary Troubles) while prosperous parents Gay Seabrook and Emerson Treacy took him to professional photographer Franklin Pangborn in Wild Poses. Spanky’s well-fed appearance reflected a loosening of the depression’s grip. Stories no longer revolved around issues of survival. The He-Man Woman Hater’s Club and golf lessons supplied frameworks for comedy. Would Alfalfa sing in the annual Follies? There was still the ongoing threat of neighborhood bully Butch, but he wasn’t a patch on sinister forces that had once preyed upon the Gang. That bucolic, on-location schoolhouse from earlier days was now replaced by a spanking clean edifice constructed on a Hal Roach soundstage. Classroom mischief was no longer calculated --- just little misunderstandings resolved within a (now) one-reel duration by Roach ingenue Rosina Lawrence. Harsh truths reflected in the early Our Gangs were now innocuous bromides where children were taught life’s lessons and adults no longer represented a threat. If anything, the grown-ups were too ineffectual. Spanky’s future with a neutered Johnny Arthur as father and presumed role model seemed anything but promising. By 1937, Our Gang was the last shorts group still ongoing at Roach, done with precision befitting a newly retrofitted feature manufacturer. Things like Two Too Young (Spanky and Alfalfa think Buckwheat and Porky are too immature to have firecrackers --- who the hell are they to judge?) and The Awful Tooth (dentistry was always ill-advised subject matter for this series) were almost as excruciating as the Metros to come, so there was little cause for regret when Roach (seated here with the Gang at his desk) finally closed the sale in 1938.

By 1935, they’d honed off rougher edges and promoted the Rascals to a level of comfort and stability denied their early talkie brethren. Much of what would eventually undermine the series at MGM began here. Our Gang now ran lemonade stands and put on impromptu shows. Spanky was fussed over by Hattie McDaniel as uniformed domestic in a distinctly middle-class home (Anniversary Troubles) while prosperous parents Gay Seabrook and Emerson Treacy took him to professional photographer Franklin Pangborn in Wild Poses. Spanky’s well-fed appearance reflected a loosening of the depression’s grip. Stories no longer revolved around issues of survival. The He-Man Woman Hater’s Club and golf lessons supplied frameworks for comedy. Would Alfalfa sing in the annual Follies? There was still the ongoing threat of neighborhood bully Butch, but he wasn’t a patch on sinister forces that had once preyed upon the Gang. That bucolic, on-location schoolhouse from earlier days was now replaced by a spanking clean edifice constructed on a Hal Roach soundstage. Classroom mischief was no longer calculated --- just little misunderstandings resolved within a (now) one-reel duration by Roach ingenue Rosina Lawrence. Harsh truths reflected in the early Our Gangs were now innocuous bromides where children were taught life’s lessons and adults no longer represented a threat. If anything, the grown-ups were too ineffectual. Spanky’s future with a neutered Johnny Arthur as father and presumed role model seemed anything but promising. By 1937, Our Gang was the last shorts group still ongoing at Roach, done with precision befitting a newly retrofitted feature manufacturer. Things like Two Too Young (Spanky and Alfalfa think Buckwheat and Porky are too immature to have firecrackers --- who the hell are they to judge?) and The Awful Tooth (dentistry was always ill-advised subject matter for this series) were almost as excruciating as the Metros to come, so there was little cause for regret when Roach (seated here with the Gang at his desk) finally closed the sale in 1938.

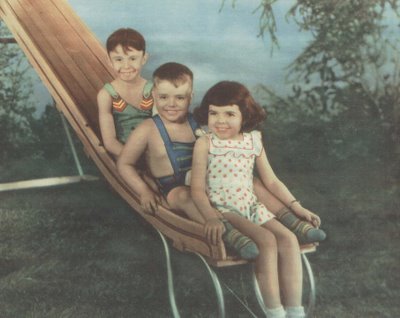

No use rehashing the later Our Gangs. Suffice to say they wheezed out in 1944. All the kids were left to fend for themselves. You’d think Metro could have at least kept them on as day players, helped with admission to a trade school ---something. Those bleak early subjects might have prepared older Rascals for what they’d face now. Books have been written about whatever became of, etc. Leonard Maltin and Richard Bann authored the best one. The fifties were barren ground for the gang before television release of the old shorts revitalized interest. A reunion of silent cast members on Art Baker’s You Asked For It was eerily effective for the malaise it revealed among the group (and Mickey Daniels seems slightly demented, as usual). Viewers expecting a glimpse of the Gang they best remembered must have been disappointed, for the silent comedies had been out of circulation for years even then, and would remain so, other than mutilated excerpts on television’s The Mischief Makers, and a small handful in the Interstate syndicated package. We wondered what had become of the talking Rascals, but information along these lines was hard to come by in the sixties, when public curiosity may well have been at its peak due to TV exposure in virtually every market. Everybody knew Alfalfa died in a knife fight over $50 (one kid at school maintained this was Pete The Pup’s fate as well). My interest was piqued when word came that Spanky was distributing home heating oil in Hendersonville, NC (still not sure about that one). Tabloids would report the surfacing of a Fatty or a Stinky, but as these were characters unknown to any period within the Gang’s twenty plus year run, one had to assume Fatty and Stinky were either liars or madmen. There was one surviving Our Gang member I did locate, and to my youthful wonderment, she stood right before me every day teaching sixth grade band…

My instrument was the clarinet, but Priscilla Call knew I was faking most of the notes, as I had no musical talent and less initiative to learn. Mrs. Call had taught band around the county school system for at least ten years. Before that, she’d attended music conservatory. Her long past career as a child actress in movies was known as well, but that was a forbidden topic among we band students. The singing cowboy host of Charlotte TV’s Little Rascals Club was rebuffed when he sought an interview, and Mrs. Call had to deal with the persistent local myth that confused her with Our Gang’s Darla Hood. She was actually Priscilla Lyon during the Hollywood years, landing there by virtue of a Hal Roach sponsored talent show she’d won back in Virginia. It was 1935, the Shirley Temple gold rush was on, and Priscilla’s mother figured on mining some of it. Eventually, the whole family landed in Culver City. The seven-year-old tested for Darla’s part in The Bohemian Girl, then decorated the chorus of The Our Gang Follies Of 1936. Priscilla tap-danced on a shine box in The Lucky Corner, and got feature work where she could. There were more aspiring moppets than buffalo head nickels, so competition was intense. She almost got to play Becky Thatcher in Selznick’s Adventures Of Tom Sawyer, but Ann Gillis prevailed. The Hollywood scene never appealed to Priscilla, so by the time she got out (in 1942), there’d be no tears of parting. Most of the band kids left her alone about the Rascals, but Mrs. Call was aware of my overpowering (if not overbearing) interest in such things, and looking back on it now, I guess both of us knew that there would someday come a reckoning.

That final morning in band found me gingerly approaching the lectern as Mrs. Call conferred with fellow musicians about an upcoming concert. Perhaps she’d not paid sufficient heed to my question so as to realize the terrible consequence in answering … Mrs. Call, Did you ever meet Lon Chaney, Jr.? Her response was a casual yes. When and where? was my next query. Oh, he was making some picture about a werewolf and I stood on the stage and watched, she said, as if that amounted to something less than the supremely momentous event in anyone’s life. My twelve-year-old euphoria must surely have alarmed her. Was Claude Rains there? Did you see Lugosi? Was Jack Pierce on the set to attend Chaney’s make-up? The questions were as rapid-fire as they were relentless. Within five minutes, I’d been relocated to a corridor outside the band room with the understanding that classes would proceed henceforth without benefit of my presence. In short, I was booted out of band. Booted, my dear baron, for knowing too much. Later sightings of Priscilla Call, even in high school, were but fleeting. She’d see me in the hall, dart quickly around a corner, or beat a hasty retreat toward a classroom. I began to think of her as a faculty equivalent of the fabled Yeti, rarely glimpsed but definitely out there. It would be 1980 before she’d finally talk, and this was during her final illness. We spent at least two hours going through scrapbooks and noting credits, many of which were unknown, even to her. She’d been in a number of features in addition to the Our Gangs, and had quite a career in radio as well. Co-stars included John and Lionel Barrymore, Ronald Reagan, Tyrone Power, Shirley Temple, Claude Rains (his daughter in Strange Holiday) --- a real galaxy of notables. Priscilla was the only Golden Age celebrity my town ever had, and I was privileged to be the one to finally take down her story. Other Little Rascals may have been more noteworthy, but this was our Rascal.

Our Gang Creeped Me Out! --- Part One

Our Gang Creeped Me Out! --- Part One

Parents often go to great lengths to impress upon children how good their lives are, and how thankful they should be for what they have. Mine needn’t have bothered. The Little Rascals got the message over with greater clarity and eloquence than any parental lecture could have achieved. I thanked Dame Fortune each Saturday morning as I munched Zero bars and watched Stymie and Spanky beg food in The Pooch. I knew better than to complain about a small thing like no color television when Farina had to bathe his little brother in water out of a duck pond. My favorite Our Gangs were those primitive, austere early talkies. All the kids were grindingly poor, often homeless, and sometimes worse, inmates in an orphan asylum. Adults were dangerous and unpredictable in the Rascal’s world. Many of my darkest assumptions about grown-ups developed while immersed in their universe. Yes, these were comedies, but a lot of them scared me but good. There’s a dreadful, screeching old harridan in Mush and Milk that still gives me gooseflesh, and the sight of a clearly psychotic Max Davidson with his carving knife poised at Farina’s throat in Moan & Groan, Inc. was the stuff of nightmare for me. Were kids that much tougher in the depression? They had to be, for the gang seemed encircled by hateful, scheming adults unwilling to make any allowance for their potential victim’s tender age. The early talking Rascals were let loose in a survival of the fittest society where kids could be starved, pets gassed (by grown-ups who would enjoy it), and orphans enslaved in remote state-sanctioned hellholes. How could a pampered sixties youth complain in the face of such alarming social documents?

There was a picturesque little general store just outside the neighborhood a lot of us frequented often, very much like the one in Helping Grandma, only this proprietor was no kindly Margaret Mann. She was, in fact, a hard, wizened crone who never forgave that extra penny due for sales tax and always dropped the plain M&M’s on the counter with sufficient force so as to shatter the outer coatings. Myrtle also maintained a hairstyle identical to that of Miss Crabtree, the only person I’d encountered in the mid-sixties to have done so (the resemblance most definitely ended there, by the way). I used to imagine that Myrtle was perhaps the embittered latter day fulfillment of all Miss Crabtree’s lost hopes and dreams, assuming, of course, that Miss Crabtree was indeed consigned to continue her solitary life teaching successive generations of (off-screen) Our Gang kids without hope of raising a family of her own. She and Myrtle did part company in that sense, however, because Myrtle had a husband, who for the few years I knew him prior to his death, acted as a kindly buffer between us and his Mush and Milk wife.

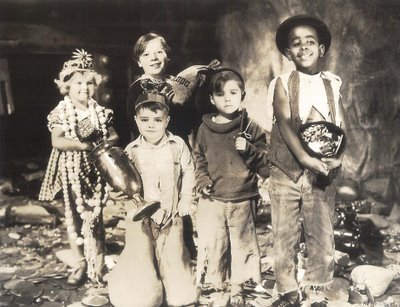

My selection of The Kid From Borneo as the scariest motion picture ever made actually arose from a basic misunderstanding of the story that has dogged me from the day I first saw it some forty-five years ago. I thought the Wild Man really was Uncle George. For some reason, I failed to pick up on the letter in the opening scene that explains the whole set-up. The parent's baleful reference to him as a black sheep suggested to me that this was some sort of genetic missing link that had somehow cropped up in the family bloodline; a savage, inarticulate thing that had years ago been sold to the circus as a freak attraction. Now Dickie Moore and Spanky have to go and reclaim Uncle George on behalf of parents too afraid, or guilt-ridden, to do it themselves. "Uncle George" was every bit as terrifying to me as he was to the gang, all the more so because he was apparently related to them. I never laughed once at this comedy --- still haven’t. When Spanky feeds Uncle George all those contents from the icebox, I know the hapless child’s just buying time before being eaten himself. After drinking port wine, the giant takes off in pursuit of the children with a knife, and for all we know, intends to use it. No amount of slapstick could relieve the dread I experienced when the mother walked into that bedroom to be reunited with her "brother." Believing Uncle George to be the woman's actual sibling, I was consumed with childish horror when she pulled back the bedspread to reveal this frightful thing she’d renounced long ago, back now to seek vengeance for his childhood abandonment. Both the parents play these scenes straight. They’re genuinely terrified at the sight of Uncle George. The whole thing became so profoundly unnerving that I finally had to turn the channel whenever The Kid From Borneo appeared. I’ve since wondered if anyone else misread this short in the same way. Watching it again this week, I’d still maintain it’s open to alternative readings (after all, we never do see the real Uncle George). Perhaps the varied menu of interpretation works to its advantage in the end. Some can embrace it as one of the funniest Our Gang shorts ever, even as it remains for this viewer the most bone-chilling two-reel horror film of all time (and that's Uncle George holding up Gang members in this group shot).

The Kid From Borneo wasn’t the only Rascals comedy with disturbing images. I’m still stunned when Farina’s playmate whacks him full-face with a heavy board in Lazy Days, resulting in a grotesquely swollen nose for the fadeout (such violence would not repeat itself until John Wayne performed a similar service for George Kennedy in The Sons Of Katie Elder). When The Wind Blows finds Jackie Cooper’s father roused from bed when his son tries to enter the house and firing a pistol through the front door. Wheezer is repeatedly whipped by a vicious stepmother in Dogs Is Dogs even as he’s starved on a tepid diet of "mush" (I always wished someone would take a baseball bat to these adult oppressors). Free Eats has two repulsive midgets posing as babies in order to loot guests at a children’s party --- I always found these characters unsettling and not the least funny. Clarence Wilson and pinch-faced wife steal the gang’s new clothes in Shrimps For A Day, later forcing them to drink castor oil. A pirate with fangs and a blood-curdling growl menaced Stymie in Shiver My Timbers. The giant that corners the gang in Mama’s Little Pirate looks fully capable of broiling them in a stew-pot and eating them whole --- he ranks second only to Uncle George for evoking nightmares. Maybe other kids took these shorts in the proper spirit and laughed through them all. Would that I could have, but clearly mine was a more timid sensibility. Still is, apparently, for even now I found it difficult getting through some of these again. Funny how certain responses can again come calling, even after forty odd years. Tomorrow’s Part Two reveals the one-time Our Gang membership of my elementary school band teacher, and the long road I traveled in getting her to finally talk about it.

A Dream Lost In The Mists Of TimeHere’s a small town theatre circa 1914 called The Dream, and it’s well named, for my idea of a dream come true would be to somehow walk through those portals and see that combination of A Woman’s Loyalty and The Million Dollar Mystery. The latter was a serial --- back when chapterplays were just getting started and attracted huge audiences. Their stories were often serialized in print as well --- magazines and newspapers breathlessly reported each installment. These three and six sheets are spectacles in and of themselves. I’d have been down every day just to see the display changes. I really like the way the posters are spread out along that courtyard entrance area. Needless to say, a sudden cloudburst might complicate things for the Dream’s management. According to a caption on the back of the photo, the location is a place called Centerville (but in what state?) and this venue later became Ryan’s BarberShop. The rest, I’m afraid, is lost to history.

A Dream Lost In The Mists Of TimeHere’s a small town theatre circa 1914 called The Dream, and it’s well named, for my idea of a dream come true would be to somehow walk through those portals and see that combination of A Woman’s Loyalty and The Million Dollar Mystery. The latter was a serial --- back when chapterplays were just getting started and attracted huge audiences. Their stories were often serialized in print as well --- magazines and newspapers breathlessly reported each installment. These three and six sheets are spectacles in and of themselves. I’d have been down every day just to see the display changes. I really like the way the posters are spread out along that courtyard entrance area. Needless to say, a sudden cloudburst might complicate things for the Dream’s management. According to a caption on the back of the photo, the location is a place called Centerville (but in what state?) and this venue later became Ryan’s BarberShop. The rest, I’m afraid, is lost to history.

The Sci-Fi Boys and The Naked Monster

The Sci-Fi Boys and The Naked Monster Director John Landis describes the Sci-Fi Boys as skinny little geek kids who were always wanting to make films when they were in school. Landis includes Steven Spielberg and George Lucas among this group, and judging by their current position, we’d have to concede that geekdom might not be an altogether bad thing. Surely it’s apparent that the geeks have taken over Hollywood, but that isn’t news. They’ve been in control for nearly thirty years, and you wonder if there’ll ever be an end to these multi-million dollar walks down memory lane. Seems Landis and his contemporaries really just want to pay homage to the pioneer monster-makers that influenced their childhoods, but yipes, this has been going on decades now --- what happens when future generations start paying their homage to these homage payers? Will the customers still be willing to pay? Recent erosion at the boxoffice would suggest a need for something new, but what can fans-to-filmmakers do but recycle? The Sci-Fi Boys is a DVD documentary that addresses the impact of fanta-pioneers (hey, have I just invented a new genre by-word?). Ackerman is chief among these, but there’s also Ray Harryhausen, Ray Bradbury, and the late George Pal. Somehow Landis made the biggest impression on me. He’s the only interview subject wearing a suit. The others are casual, sometimes ultra-so. I guess that’s what happens when the geeks take over.

Director John Landis describes the Sci-Fi Boys as skinny little geek kids who were always wanting to make films when they were in school. Landis includes Steven Spielberg and George Lucas among this group, and judging by their current position, we’d have to concede that geekdom might not be an altogether bad thing. Surely it’s apparent that the geeks have taken over Hollywood, but that isn’t news. They’ve been in control for nearly thirty years, and you wonder if there’ll ever be an end to these multi-million dollar walks down memory lane. Seems Landis and his contemporaries really just want to pay homage to the pioneer monster-makers that influenced their childhoods, but yipes, this has been going on decades now --- what happens when future generations start paying their homage to these homage payers? Will the customers still be willing to pay? Recent erosion at the boxoffice would suggest a need for something new, but what can fans-to-filmmakers do but recycle? The Sci-Fi Boys is a DVD documentary that addresses the impact of fanta-pioneers (hey, have I just invented a new genre by-word?). Ackerman is chief among these, but there’s also Ray Harryhausen, Ray Bradbury, and the late George Pal. Somehow Landis made the biggest impression on me. He’s the only interview subject wearing a suit. The others are casual, sometimes ultra-so. I guess that’s what happens when the geeks take over.

Ackerman used to wear suits too, back when he was trying to gain mainstream respect for a movie genre critics had been blowing off for years. During the sixties in particular, FJA was a lone ambassador for the serious appreciation of science-fiction and horror, but all the thanks he got was in the form of letters written in ten-year old scrawl (mine included!). Those dark jackets and narrow ties were reassurance for the mothers of America that this was no disheveled pied piper leading their children to wreck and ruin. In fact, Ackerman cut a dashing figure and was similar in appearance if not temperament to another mustachioed notable, Vincent Price. The Ackerman images shown here illustrate the transition he made as the genre he championed gained in approval. On top, we see FJA delivering a scholarly overview of sci-fi’s history in an interview that was shot in 1970 (it’s an extra on the DVD). This well-groomed, professorial figure is determined to get respect for his passion, and despite his sometimes-pompous declamations; you really root for him to pull it off. As we now know, Ackerman’s vindication was still several years in the offing, but when it came, it was glorious. Within a decade, he’d go from a jack to a king. The bottom capture shows Ackerman after his side has won. It’s 1983, and he’s appearing on a talk segment commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of King Kong. Nobody (but FJA and his followers) cared less when Kong was thirty, or even forty, but this was a new day, a post- Star Wars day, and now Ackerman was riding high on a boxoffice rocket he and his magazine had helped launch. Endorsements from the very filmmakers responsible for these genre leviathans gave him cultural capital he'd not dreamed of when he did that 1970 interview. No more button-down for him --- open collars and leisure suits from now on! Forrest J. Ackerman is eighty-nine, going on ninety in November, and indisputably the grand old man of fandom. He collects honors the way his followers collect old Famous Monsters magazines, and The Sci-Fi Boys is a fitting and enjoyable tribute. It would be great to see him reach 100 and be feted again.

The Naked Monster is another of those homages, but this one’s different in that it spoofs sci-fi relics on one hand and pays tribute to their surviving cast members with the other (here's a still montage). Most of it was shot around 1984 when Airplane and its imitators were making fair game of old movie conventions, and scattershot parody was gaining ground as the fresh new formula for screen comedy. Now it’s twenty years later and this sort of humor’s been pretty much strip-mined, but producer-writer and co-director Ted Newsom has a real knack for the essential absurdity of his low-budget sci-fi prototypes, and laughs he gets are all the more impressive in view of the fact he shot this on Super 8mm (including video inserts) within a budget equivalent to contents of a very small piggy bank. Stock footage and library music was used. I really liked the overlay of familiar themes throughout, and fans can have themselves a visual Scrabble game trying to ID familiar shots from various trailers and public domain features. A real treat here is the parade of hallowed names from the fifties. Kenneth Tobey leads off, and there are cameos from John Agar, Lori Nelson, Gloria Talbott, and many others. Some of them don’t even appear to have left the house. Talbott does a telephone scene beneath a portrait of herself as a long ago ingenue. She would have been an interesting person to talk to, though for every one question she ever got about All That Heaven Allows or We’re No Angels, there must have been a hundred about I Married A Monster From Outer Space and The Cyclops. Newsom does a nice epilogue salute to these veteran players, most of whom have since passed on. Those who are still with us include leading lady Brinke Stevens and Linnea Quigley, two names familiar to me by virtue of each having appeared in close to a hundred low-budget horrors. These are staggering numbers compared with the comparatively few genre ventures their fifties forebears took on. Will Brinke (51) and Linnea (48) be called out of retirement someday for guest roles in some future fan homage to Cheerleader Massacre or Beach Babes From Beyond? It could be sooner than we think, as these two actresses have been around since at least the mid-seventies (you can get The Naked Monster HERE).

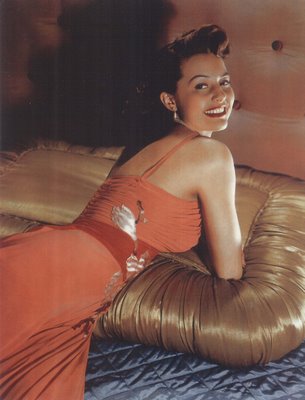

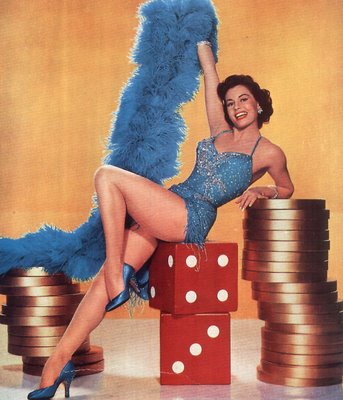

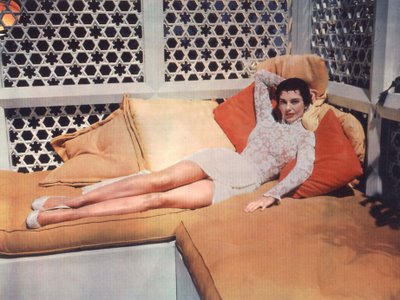

Monday Glamour Starter --- Cyd Charisse

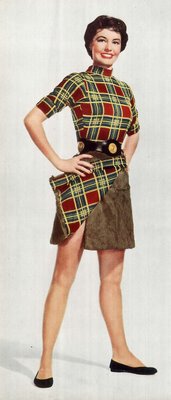

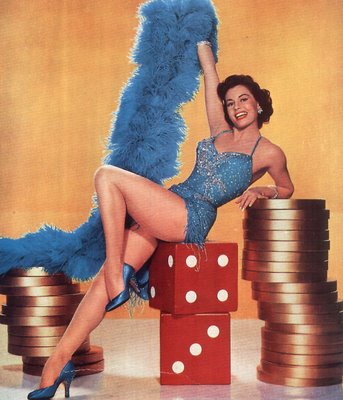

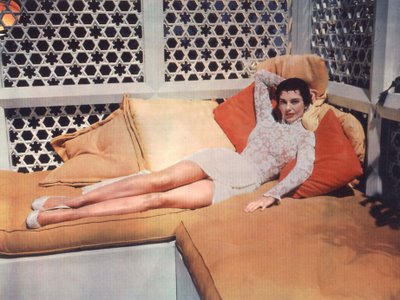

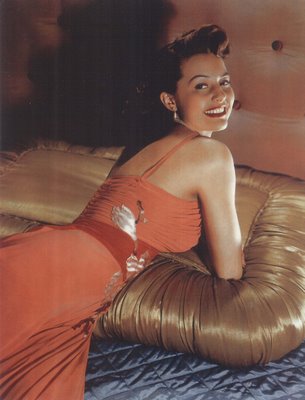

Monday Glamour Starter --- Cyd Charisse Actresses like Cyd Charisse aren’t easy to write about, since there’s just no conflict, scandal, or tragedy to juice up the narrative. I’ve not come across the first mention of personal or professional travails, bad kids, substance abuse --- nothing. Then it occurs to me that if you’re going to dance for a living, a thing that surely requires a tremendously disciplined lifestyle, chances are there won’t be much time or inclination to devote toward those vices that laid so many Glamour Starters low. I do believe that Cyd Charisse is also the first of our Monday subjects to have remained wed for fifty years (well, 58 to be exact, with husband Tony Martin). After Mabel Normand, Gail Russell, and Gloria Grahame, she’s a breath of Spring. There’s an official website HERE, and I understand she still gets out occasionally for tributes and such. Cyd Charisse is eighty-five at present, and looks considerably younger. She’s about the last surviving member of the great MGM musical team, although watching Brigadoon last night reminded me that Van Johnson just celebrated his ninetieth birthday. Search results keep mentioning her legs. Well, she danced, so that’s natural enough, but she also acted from time to time. By the time the music stopped, it was too late to gain a foothold in drama, as the studio system had by then collapsed, and work was limited to television and features far less distinguished than those she’d enhanced at Metro.

Actresses like Cyd Charisse aren’t easy to write about, since there’s just no conflict, scandal, or tragedy to juice up the narrative. I’ve not come across the first mention of personal or professional travails, bad kids, substance abuse --- nothing. Then it occurs to me that if you’re going to dance for a living, a thing that surely requires a tremendously disciplined lifestyle, chances are there won’t be much time or inclination to devote toward those vices that laid so many Glamour Starters low. I do believe that Cyd Charisse is also the first of our Monday subjects to have remained wed for fifty years (well, 58 to be exact, with husband Tony Martin). After Mabel Normand, Gail Russell, and Gloria Grahame, she’s a breath of Spring. There’s an official website HERE, and I understand she still gets out occasionally for tributes and such. Cyd Charisse is eighty-five at present, and looks considerably younger. She’s about the last surviving member of the great MGM musical team, although watching Brigadoon last night reminded me that Van Johnson just celebrated his ninetieth birthday. Search results keep mentioning her legs. Well, she danced, so that’s natural enough, but she also acted from time to time. By the time the music stopped, it was too late to gain a foothold in drama, as the studio system had by then collapsed, and work was limited to television and features far less distinguished than those she’d enhanced at Metro.

There weren’t many ballerinas on studio payrolls in the forties. Vera Zorina was one, but she was back and forth between Fox and Paramount, and neither developed a niche for her. Ballet was a specialty even at dance conscious MGM, but there was often enough a need for someone accomplished in that area, so Cyd Charisse got a contract and plenty of visibility in a series of big musicals during the forties. Scattered amongst these invitations to the dance were supporting parts in melodramas and thrillers. Tension was a 1950 noir where she played nice girl rival to sluttish Audrey Totter, so guess who the notices singled out. East Side, West Side found her down the line behind two prominent females, Barbara Stanwyck and Ava Gardner. She’d been at Metro since 1946, but leads in musicals had collapsed in the face of accident and off-timing. She broke her leg and thus missed out on Easter Parade (that must have been traumatic), while Leslie Caron got An American In Paris when Charisse had a child. The big break arrived with Singin’ In The Rain, where she really commanded attention and MGM finally got serious about making better use of her. Unfortunately, the era of big musicals was itself headed for the rocks, and though she’d participate in some of its last glorious encores, Cyd Charisse would bask but a brief moment in stardom’s glow.

There weren’t many ballerinas on studio payrolls in the forties. Vera Zorina was one, but she was back and forth between Fox and Paramount, and neither developed a niche for her. Ballet was a specialty even at dance conscious MGM, but there was often enough a need for someone accomplished in that area, so Cyd Charisse got a contract and plenty of visibility in a series of big musicals during the forties. Scattered amongst these invitations to the dance were supporting parts in melodramas and thrillers. Tension was a 1950 noir where she played nice girl rival to sluttish Audrey Totter, so guess who the notices singled out. East Side, West Side found her down the line behind two prominent females, Barbara Stanwyck and Ava Gardner. She’d been at Metro since 1946, but leads in musicals had collapsed in the face of accident and off-timing. She broke her leg and thus missed out on Easter Parade (that must have been traumatic), while Leslie Caron got An American In Paris when Charisse had a child. The big break arrived with Singin’ In The Rain, where she really commanded attention and MGM finally got serious about making better use of her. Unfortunately, the era of big musicals was itself headed for the rocks, and though she’d participate in some of its last glorious encores, Cyd Charisse would bask but a brief moment in stardom’s glow.

Dancing was where her genius lay. The singing voice had to be dubbed, for Charisse was said to have been "tone deaf." She also had an aloof quality that came across even in motion --- witness her cool vamping of Gene Kelly in Singin’ In The Rain and Fred Astaire during the Girl Hunt number from The Bandwagon. At five-foot nine, she was imposing, and more convincing when serious. She never had the line in perk that sustained Debbie Reynolds, Jane Powell, and the rest. Charisse was more the self-contained type, and that made her seem a little remote between dance highlights. She warded off Kelly and Astaire on several occasions --- their characters were usually obliged to work a little harder at winning her. The Bandwagon and It’s Always Fair Weather are probably her two best musicals leads, though Brigadoon played better for me than its reputation would suggest. She looks (and dances) great in Silk Stockings, though her Garbo update (of Ninotchka) requires she give partner Astaire the ice for much of the show. Could audiences have confused these chilly roles with the offscreen Cyd Charisse? Party Girl was an unexpected meeting with director Nicholas Ray and leading man Robert Taylor. Here she danced again and made beautiful music with Bad Bob in one of his darkest and most satisfying post-war performances (the French DVD is available at THIS LINK, and it’s first-rate). After Party Girl, there were features in Europe and television stateside. Two Weeks In Another Town was a reunion with director Vincente Minnelli, and though her part was said to have been heavily cut, this is still an unsung masterpiece, even better, to my mind, than The Bad and The Beautiful. She was unsympathetic again in Something’s Got To Give, but that never finished comedy would only be recalled as Marilyn Monroe’s final appearance on film. The Unsightly Seventies found Charisse among passengers on The Love Boat, and there would be a visit to Fantasy Island. Her participation in these was less dispiriting because you never felt as though she really needed the work. Desperation among veterans doing television "guest" work was something a trained viewer eye could unfailingly sense, but not here. Charisse has maintained her dignity and the public’s regard throughout a long and (we hope) happy retirement. Nice to see one turn out this way.

Dancing was where her genius lay. The singing voice had to be dubbed, for Charisse was said to have been "tone deaf." She also had an aloof quality that came across even in motion --- witness her cool vamping of Gene Kelly in Singin’ In The Rain and Fred Astaire during the Girl Hunt number from The Bandwagon. At five-foot nine, she was imposing, and more convincing when serious. She never had the line in perk that sustained Debbie Reynolds, Jane Powell, and the rest. Charisse was more the self-contained type, and that made her seem a little remote between dance highlights. She warded off Kelly and Astaire on several occasions --- their characters were usually obliged to work a little harder at winning her. The Bandwagon and It’s Always Fair Weather are probably her two best musicals leads, though Brigadoon played better for me than its reputation would suggest. She looks (and dances) great in Silk Stockings, though her Garbo update (of Ninotchka) requires she give partner Astaire the ice for much of the show. Could audiences have confused these chilly roles with the offscreen Cyd Charisse? Party Girl was an unexpected meeting with director Nicholas Ray and leading man Robert Taylor. Here she danced again and made beautiful music with Bad Bob in one of his darkest and most satisfying post-war performances (the French DVD is available at THIS LINK, and it’s first-rate). After Party Girl, there were features in Europe and television stateside. Two Weeks In Another Town was a reunion with director Vincente Minnelli, and though her part was said to have been heavily cut, this is still an unsung masterpiece, even better, to my mind, than The Bad and The Beautiful. She was unsympathetic again in Something’s Got To Give, but that never finished comedy would only be recalled as Marilyn Monroe’s final appearance on film. The Unsightly Seventies found Charisse among passengers on The Love Boat, and there would be a visit to Fantasy Island. Her participation in these was less dispiriting because you never felt as though she really needed the work. Desperation among veterans doing television "guest" work was something a trained viewer eye could unfailingly sense, but not here. Charisse has maintained her dignity and the public’s regard throughout a long and (we hope) happy retirement. Nice to see one turn out this way.

America's Boyfriend

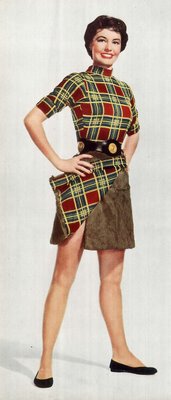

America's Boyfriend Charles "Buddy" Rogers is best remembered as Mary Pickford’s last husband. He was also one of the more accessible of silent film stars when it came time for interviews or tributes to that long vanished era. Buddy outlived virtually all of his male contemporaries, mostly because he started young, and seems to have taken pretty good care of himself (living until 1999). He was an accomplished raconteur and steadfast companion to Pickford, even as she withdrew behind the curtains at Pickfair and remained in seclusion until her death in 1979. What a lot of people forget about Rogers is just what a big name he was in his own right. It didn’t last long, and came right on the cusp of Paramount’s transition to sound, but he was one of their principal names and headlined a number of early sound comedies and musicals that have all but disappeared today. Most of these were light and youth oriented. Buddy was billed as America’s Boy Friend and his vehicles were peppy and predictable --- as disposable then as they are forgotten now. When MCA bought the pre-49 Paramount library for television release in the late fifties, most of the Buddy Rogers oeuvre made its way to broadcasters, but it wouldn’t be long before these relics were consigned to distributor’s storage shelves, never to see the light of day again. Only one resurfaced later, and Buddy’s presence was only incidental to the early two-color Technicolor that distinguished Follow Thru, a 1930 golfing comedy that was amazingly well preserved and probably remains the best surviving example of the early color process.

Charles "Buddy" Rogers is best remembered as Mary Pickford’s last husband. He was also one of the more accessible of silent film stars when it came time for interviews or tributes to that long vanished era. Buddy outlived virtually all of his male contemporaries, mostly because he started young, and seems to have taken pretty good care of himself (living until 1999). He was an accomplished raconteur and steadfast companion to Pickford, even as she withdrew behind the curtains at Pickfair and remained in seclusion until her death in 1979. What a lot of people forget about Rogers is just what a big name he was in his own right. It didn’t last long, and came right on the cusp of Paramount’s transition to sound, but he was one of their principal names and headlined a number of early sound comedies and musicals that have all but disappeared today. Most of these were light and youth oriented. Buddy was billed as America’s Boy Friend and his vehicles were peppy and predictable --- as disposable then as they are forgotten now. When MCA bought the pre-49 Paramount library for television release in the late fifties, most of the Buddy Rogers oeuvre made its way to broadcasters, but it wouldn’t be long before these relics were consigned to distributor’s storage shelves, never to see the light of day again. Only one resurfaced later, and Buddy’s presence was only incidental to the early two-color Technicolor that distinguished Follow Thru, a 1930 golfing comedy that was amazingly well preserved and probably remains the best surviving example of the early color process.

Following Mary Pickford’s retirement, Buddy continued with his band (he could play almost any instrument) and dabbled in production. His Paramount work is now owned by Universal. The likelihood of a DVD release is nil. Too bad, because these would be interesting examples of what youth audiences was lining up to see during the early thirties. By the way, those Paramount contract lovelies flanking Buddy in this publicity shot include, from left to right, Josephine Dunn, Carol Lombard (before she added the "e"), Kathryn Crawford, and Virginia Bruce. The movie is Safety in Numbers, a roguish revel of love, laughs, and lyrics wherein the Joy Boy inherits millions and gets an education in song, dance, and lingerie from five luscious ladies on a skyscraper. Sounds sure-fire to me …

Following Mary Pickford’s retirement, Buddy continued with his band (he could play almost any instrument) and dabbled in production. His Paramount work is now owned by Universal. The likelihood of a DVD release is nil. Too bad, because these would be interesting examples of what youth audiences was lining up to see during the early thirties. By the way, those Paramount contract lovelies flanking Buddy in this publicity shot include, from left to right, Josephine Dunn, Carol Lombard (before she added the "e"), Kathryn Crawford, and Virginia Bruce. The movie is Safety in Numbers, a roguish revel of love, laughs, and lyrics wherein the Joy Boy inherits millions and gets an education in song, dance, and lingerie from five luscious ladies on a skyscraper. Sounds sure-fire to me …

Lon Chaney Died 76 Years Ago TodayThe monster magazines used to trumpet, Lon Chaney Shall Not Die!, and they were right, to the extent that still reproduction kept the man’s image alive, but for those of us confined to unimaginative television markets, the possibility of this silent actor turning up on our home screens was remote at best, other than an occasional glimpse on Fractured Flickers. It was TCM and laser discs that brought Chaney out of his archival refuge, and even though a number of the films were letdowns (particularly the MGM vehicles), there was no argument as to Chaney’s truly unique position in film history. He died August 26, 1930. Kevin Brownlow’s excellent documentary provides first-hand recollections from then-impressionable boys whose mourning over the loss persists to this day (and most of them would have to be in their eighties, or more, by now). Did they identify with Chaney as society’s truest pariah? Other stars dabbled in the role of outcast (recent subject James Dean among them), but you knew these guys could have any girl they wanted if their innate movie star appeal were switched on. Chaney’s the real Miracle Man who never played celebrity. He was the working man’s actor (note the cap in this portrait --- looks like he’s headed for work at a construction site) who declared there was no Lon Chaney after those stage lights went down.

Lon Chaney Died 76 Years Ago TodayThe monster magazines used to trumpet, Lon Chaney Shall Not Die!, and they were right, to the extent that still reproduction kept the man’s image alive, but for those of us confined to unimaginative television markets, the possibility of this silent actor turning up on our home screens was remote at best, other than an occasional glimpse on Fractured Flickers. It was TCM and laser discs that brought Chaney out of his archival refuge, and even though a number of the films were letdowns (particularly the MGM vehicles), there was no argument as to Chaney’s truly unique position in film history. He died August 26, 1930. Kevin Brownlow’s excellent documentary provides first-hand recollections from then-impressionable boys whose mourning over the loss persists to this day (and most of them would have to be in their eighties, or more, by now). Did they identify with Chaney as society’s truest pariah? Other stars dabbled in the role of outcast (recent subject James Dean among them), but you knew these guys could have any girl they wanted if their innate movie star appeal were switched on. Chaney’s the real Miracle Man who never played celebrity. He was the working man’s actor (note the cap in this portrait --- looks like he’s headed for work at a construction site) who declared there was no Lon Chaney after those stage lights went down.

Just to make the separation with Hollywood complete, he used to take vacations deep in the woods. Surviving home movies have an austere and rustic quality you’d never get from present day stars on holiday. When Lon, Jr. was apparently still-born, his father scooped up the infant and rushed him outside to a near-freezing mountain stream, where he induced breathing by immersing little Creighton in the water. Chaney was one actor who understood something (maybe too much) about real life. His kind of hardship was very nineteenth century, and it’s still a shock to look upon that weathered face and realize this man died when he was only forty-seven.

Just to make the separation with Hollywood complete, he used to take vacations deep in the woods. Surviving home movies have an austere and rustic quality you’d never get from present day stars on holiday. When Lon, Jr. was apparently still-born, his father scooped up the infant and rushed him outside to a near-freezing mountain stream, where he induced breathing by immersing little Creighton in the water. Chaney was one actor who understood something (maybe too much) about real life. His kind of hardship was very nineteenth century, and it’s still a shock to look upon that weathered face and realize this man died when he was only forty-seven.

So what was his secret? In an era of celebrity that played at being aloof, he was genuine. Authentic Chaney autographs are about as plentiful as feathers on a frog. Fake ones are offered daily by dauntless e-bay hucksters --- I’ve seen a few signed with felt tips. Well, if collectors are gullible enough to buy these, why not just add Have a Nice Day with a smiley face and be done with it? Folks in the twenties reserved a special place in their complicated psyches for Lon. Writer David Skaal (all his books are great) says he evoked memories of the Great War and the horrific injuries inflicted during that. Others maintain he brought the forbidden pleasures of a travelling freak show into neighborhood theatres. It’s probably some of both, plus a lot of unwholesome explanations nobody’s yet thought of. A casual look at The Penalty will give you all the sick you need --- this 1920 corker can still shock viewers today with its unbridled depravity.

So what was his secret? In an era of celebrity that played at being aloof, he was genuine. Authentic Chaney autographs are about as plentiful as feathers on a frog. Fake ones are offered daily by dauntless e-bay hucksters --- I’ve seen a few signed with felt tips. Well, if collectors are gullible enough to buy these, why not just add Have a Nice Day with a smiley face and be done with it? Folks in the twenties reserved a special place in their complicated psyches for Lon. Writer David Skaal (all his books are great) says he evoked memories of the Great War and the horrific injuries inflicted during that. Others maintain he brought the forbidden pleasures of a travelling freak show into neighborhood theatres. It’s probably some of both, plus a lot of unwholesome explanations nobody’s yet thought of. A casual look at The Penalty will give you all the sick you need --- this 1920 corker can still shock viewers today with its unbridled depravity.

The Chaney mystery is abetted in no small way by the unavailability of his films. So many good ones are lost. Books have been written about movies we’ll probably never see. I know some guys whose first request in the afterlife will be a screening of London After Midnight, followed by, perhaps, A Blind Bargain. Any unseen footage of Chaney is like a rope of pearls. When they found an odd reel of the otherwise lost Thunder, it was an experience akin to entering Tutankhamun’s tomb. Somehow it’s appropriate that much of Chaney go missing. We can look at the surviving stills and dream of the miracles he wrought. Based on the expectations we’ve developed over the intervening decades, the features would almost certainly be disappointing, so maybe some of his mystique is best left to our imaginations.

The Chaney mystery is abetted in no small way by the unavailability of his films. So many good ones are lost. Books have been written about movies we’ll probably never see. I know some guys whose first request in the afterlife will be a screening of London After Midnight, followed by, perhaps, A Blind Bargain. Any unseen footage of Chaney is like a rope of pearls. When they found an odd reel of the otherwise lost Thunder, it was an experience akin to entering Tutankhamun’s tomb. Somehow it’s appropriate that much of Chaney go missing. We can look at the surviving stills and dream of the miracles he wrought. Based on the expectations we’ve developed over the intervening decades, the features would almost certainly be disappointing, so maybe some of his mystique is best left to our imaginations.