skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Thank You, Fox, For Mr. MotoPeter Lorre once said he had no memory of doing the Mr. Moto series. This was years after the fact, of course, and we know he had a low opinion of these "B" (in name only) mysteries, particularly after the first couple of entries when he realized Fox had no intention of giving him the varied roles he craved. That quest to avoid typecasting was what brought him over from Columbia in the first place, but honestly, how could you avoid typecasting Peter Lorre? There was something vaguely sinister about his countenance (most of the time it wasn’t even vague) and that voice was never less than unsettling, particularly when it dipped toward a frenzied growl or soared upward to shrieking malevolence. I just don’t know how many conventional parts this man could have done. Mr. Moto probably comes closest, yet Lorre plays it in such wildly unconventional terms as to make Moto’s status as hero a little doubtful, which works very much to the film’s good. Maybe Lorre was just ahead of his time (there’s certainly no argument as to that among his fans), for his performances as Moto are so engaging, so unpredictable, that we tend to think of them as "modern." Not that modern filmmakers are likely to come up with a character as arresting as this one, but Lorre’s style has an appeal to present day sensibilities, for never at any moment does he pander to cliché, much less accommodate establishment notions of what a movie hero "should" be. There was something profoundly mysterious about this man, as if things were swirling about his mind that none of us could ever comprehend, let alone anticipate. Lorre gives these Motos a tension and menacing quality that only he possessed --- the idea of anyone else assuming that role is just unthinkable.

Thank You, Fox, For Mr. MotoPeter Lorre once said he had no memory of doing the Mr. Moto series. This was years after the fact, of course, and we know he had a low opinion of these "B" (in name only) mysteries, particularly after the first couple of entries when he realized Fox had no intention of giving him the varied roles he craved. That quest to avoid typecasting was what brought him over from Columbia in the first place, but honestly, how could you avoid typecasting Peter Lorre? There was something vaguely sinister about his countenance (most of the time it wasn’t even vague) and that voice was never less than unsettling, particularly when it dipped toward a frenzied growl or soared upward to shrieking malevolence. I just don’t know how many conventional parts this man could have done. Mr. Moto probably comes closest, yet Lorre plays it in such wildly unconventional terms as to make Moto’s status as hero a little doubtful, which works very much to the film’s good. Maybe Lorre was just ahead of his time (there’s certainly no argument as to that among his fans), for his performances as Moto are so engaging, so unpredictable, that we tend to think of them as "modern." Not that modern filmmakers are likely to come up with a character as arresting as this one, but Lorre’s style has an appeal to present day sensibilities, for never at any moment does he pander to cliché, much less accommodate establishment notions of what a movie hero "should" be. There was something profoundly mysterious about this man, as if things were swirling about his mind that none of us could ever comprehend, let alone anticipate. Lorre gives these Motos a tension and menacing quality that only he possessed --- the idea of anyone else assuming that role is just unthinkable.

I was surprised and delighted to see Moto dispatching his opponents so casually. None of this shoot the gun out of their hand nonsense. He just fires away, then stands over the man’s corpse and softly intones the fact we’re well rid of him. Moto doesn’t subdue his enemies --- he finishes them off. Anyone mucking about with him is likely to die. I don’t know how the Code let some of this by. There’s a peerless moment in Think Fast, Mr. Moto where he interrupts a would-be shipboard burglary, judo-tosses the rather unpresupposing henchman about the room, then hurls the clearly defeated miscreant overboard into an ink-black sea --- so much for due process and "bringing them to justice." In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he manipulates the villains into killing each other off, then smirks off the whole thing whilst surveying a room littered with their remains. Who but Peter Lorre could execute all of this with such finesse? I understand he was tight in the grip of morphine addiction during production of these shows. Director Norman Foster said Lorre was so weakened that a mere flight of stairs was beyond him. In fact, the actor came out of a sanitarium to do the first Moto. You’d not know it by watching, though (and co-workers never detected problems either). Lorre picked up the habit in Berlin, where a combination of tuberculosis and a bungled appendectomy left him in chronic pain. Those procedures they did on Lorre (there were two whacks at his appendix) sound like something out of Dr. Moreau’s House Of Pain. Must have been hell getting sick in Berlin during the twenties.

I was surprised and delighted to see Moto dispatching his opponents so casually. None of this shoot the gun out of their hand nonsense. He just fires away, then stands over the man’s corpse and softly intones the fact we’re well rid of him. Moto doesn’t subdue his enemies --- he finishes them off. Anyone mucking about with him is likely to die. I don’t know how the Code let some of this by. There’s a peerless moment in Think Fast, Mr. Moto where he interrupts a would-be shipboard burglary, judo-tosses the rather unpresupposing henchman about the room, then hurls the clearly defeated miscreant overboard into an ink-black sea --- so much for due process and "bringing them to justice." In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he manipulates the villains into killing each other off, then smirks off the whole thing whilst surveying a room littered with their remains. Who but Peter Lorre could execute all of this with such finesse? I understand he was tight in the grip of morphine addiction during production of these shows. Director Norman Foster said Lorre was so weakened that a mere flight of stairs was beyond him. In fact, the actor came out of a sanitarium to do the first Moto. You’d not know it by watching, though (and co-workers never detected problems either). Lorre picked up the habit in Berlin, where a combination of tuberculosis and a bungled appendectomy left him in chronic pain. Those procedures they did on Lorre (there were two whacks at his appendix) sound like something out of Dr. Moreau’s House Of Pain. Must have been hell getting sick in Berlin during the twenties.

Don’t confuse Mr. Moto with other mysteries. These aren’t plodding whodunits, but vigorous, globetrotting adventure yarns, quite belying their supposed "B" economies. Fox's backlot is loaded with extras, sets are handsomely appointed, and supporting casts are a who’s-who of character legends. You know you’re in good company when a door opens and John Carridine walks in, or Sidney Blackmer, or Sig Rumann --- the list goes on. I checked out a few numbers in an effort to figure out how such modest 65 minute movies could look so rich. Think Fast, Mr. Moto was the first in the series. It had a negative cost of $181,000. That’s a typical "B" budget, but this picture sure doesn’t look it. Producer Sol Wurtzel (shown here watching Shirley Temple’s wheelbarrow ride) had access to all the standing sets at Fox. After Four Men and A Prayer, The Baroness and The Butler, or some similar big one would clear out, the Moto unit would move in. All eight entries in this series made money. Think Fast was by far the biggest with $277,000 in domestic rentals, $226,000 foreign, and a final profit of $134,000. From there, the Motos slipped in terms of revenue --- Mr. Moto Takes A Chance was just $38,000 to the good, and Mr. Moto’s Gamble took only $27,000 in profit. Still, none of these pictures ever lost a dime, though I wonder if the series would have continued much longer, even were it not for the intervention of World War II. Of the Fox series in production around 1939, the Motos were the least remunerative --- Charlie Chan, The Jones Family, and Jane Withers were all performing better, though not by that substantial a margin (by the way, this little gag drawing of Chan, Moto, and Sherlock Holmes looking for their soundstage appeared in a 1939 Fox sales manual sent to exhibitors).

Don’t confuse Mr. Moto with other mysteries. These aren’t plodding whodunits, but vigorous, globetrotting adventure yarns, quite belying their supposed "B" economies. Fox's backlot is loaded with extras, sets are handsomely appointed, and supporting casts are a who’s-who of character legends. You know you’re in good company when a door opens and John Carridine walks in, or Sidney Blackmer, or Sig Rumann --- the list goes on. I checked out a few numbers in an effort to figure out how such modest 65 minute movies could look so rich. Think Fast, Mr. Moto was the first in the series. It had a negative cost of $181,000. That’s a typical "B" budget, but this picture sure doesn’t look it. Producer Sol Wurtzel (shown here watching Shirley Temple’s wheelbarrow ride) had access to all the standing sets at Fox. After Four Men and A Prayer, The Baroness and The Butler, or some similar big one would clear out, the Moto unit would move in. All eight entries in this series made money. Think Fast was by far the biggest with $277,000 in domestic rentals, $226,000 foreign, and a final profit of $134,000. From there, the Motos slipped in terms of revenue --- Mr. Moto Takes A Chance was just $38,000 to the good, and Mr. Moto’s Gamble took only $27,000 in profit. Still, none of these pictures ever lost a dime, though I wonder if the series would have continued much longer, even were it not for the intervention of World War II. Of the Fox series in production around 1939, the Motos were the least remunerative --- Charlie Chan, The Jones Family, and Jane Withers were all performing better, though not by that substantial a margin (by the way, this little gag drawing of Chan, Moto, and Sherlock Holmes looking for their soundstage appeared in a 1939 Fox sales manual sent to exhibitors).

One thing that sustained the Motos was judo action introduced in the first, then emphasized further in subsequent entries after positive audience reaction called for more of the exotic combat technique. These were days Lorre could stay home, for he never went near any of the strenuous stuff, but had a stuntman, Harvey Perry, who matched him physically and proved an effective double for all the fights. My info suggests that Lorre started out with Fox in 1936 at $750 a week, but the record also reflects he got $10,000 for each of the Motos. That may have been the sweetener necessary to keep him on the job for these things, though it was nothing like $40,000 per show Warner Oland pulled down for Charlie Chans he’d done. On one occasion, crew member’s idea of a practical joke found Lorre’s wallet and ID replaced with a fake just before he left the lot for home. This would be the time he’d get pulled by traffic cops, but imagine their surprise when Lorre produced a card identifying him as Mr. Moto --- Japanese Spy. Fortunately, the movie fan patrolman understood the jibe on Lorre, and turned him loose, but picture such a gag being executed after Pearl Harbor, such a short time later. Just as he’d wearied of being spat on in Berlin for his all-too-convincing portrayal of the child murderer in M, now Lorre bristled at kids addressing him as Mr. Moto and asking for judo demonstrations. Fox added insult to injury when they sought him to play red herring for The Ritz Brothers in their sign-off vehicle for the company, The Gorilla. It was definitely time to powder out of Fox --- nearly four years of being "sold down the river" (as he put it) was quite enough for Lorre. As great as he’d later be with Bogart, Greenstreet, and other screen partners, he’d never have a part like Moto again. The best evidence of his greatness in that role is presently on display in Volume 1 of Fox’s new DVD box set containing four of the eight series entries. They are all fantastic. I only await reassurance from Fox that the remaining titles are forthcoming.

One thing that sustained the Motos was judo action introduced in the first, then emphasized further in subsequent entries after positive audience reaction called for more of the exotic combat technique. These were days Lorre could stay home, for he never went near any of the strenuous stuff, but had a stuntman, Harvey Perry, who matched him physically and proved an effective double for all the fights. My info suggests that Lorre started out with Fox in 1936 at $750 a week, but the record also reflects he got $10,000 for each of the Motos. That may have been the sweetener necessary to keep him on the job for these things, though it was nothing like $40,000 per show Warner Oland pulled down for Charlie Chans he’d done. On one occasion, crew member’s idea of a practical joke found Lorre’s wallet and ID replaced with a fake just before he left the lot for home. This would be the time he’d get pulled by traffic cops, but imagine their surprise when Lorre produced a card identifying him as Mr. Moto --- Japanese Spy. Fortunately, the movie fan patrolman understood the jibe on Lorre, and turned him loose, but picture such a gag being executed after Pearl Harbor, such a short time later. Just as he’d wearied of being spat on in Berlin for his all-too-convincing portrayal of the child murderer in M, now Lorre bristled at kids addressing him as Mr. Moto and asking for judo demonstrations. Fox added insult to injury when they sought him to play red herring for The Ritz Brothers in their sign-off vehicle for the company, The Gorilla. It was definitely time to powder out of Fox --- nearly four years of being "sold down the river" (as he put it) was quite enough for Lorre. As great as he’d later be with Bogart, Greenstreet, and other screen partners, he’d never have a part like Moto again. The best evidence of his greatness in that role is presently on display in Volume 1 of Fox’s new DVD box set containing four of the eight series entries. They are all fantastic. I only await reassurance from Fox that the remaining titles are forthcoming.

Monday Glamour Starter --- Gail RussellGail Russell’s fate was sealed when friends from school told a Paramount talent scout about the Hedy Lamarr of Santa Monica High, which was Gail alright, only she couldn’t act and didn’t much want to. This girl had as much business being a movie star as I would being an astronaut. The price she paid in showing up for that audition was a lifetime’s damnation, for no one got less joy out of celebrity-dom than Gail Russell. Nineteen when she walked through the gates, Gail’s looks got the pass others would have waited years to earn, but then, most of them would had have more experience, if not talent. Gail had neither. She knew it and so did Paramount, but they had departments to fix all that, and the girl was nothing if not pliable. Terrified might be a better word, for she was beset with stage fright approaching paralysis, and crying fits, then vomiting, would often as not conclude each take. She’d become a joke among producers in the know as to her limitations, but they were committed to the packaging and sale of Gail Russell, and toward that end, thrust her almost immediately into leads. Veterans such as Ginger Rogers and Ray Milland were patient with her --- perhaps they a saw a mirror of their own youthful fears in her doe-eyes, but directors like The Uninvited’s Lewis Allen were charged with getting a performance out of her, and that sometimes took hours, if not days, of blown takes and gentle guidance. Allen later said whatever useful footage they got out of Russell had to be cobbled together from brief takes and single line readings, but the camera showed mercy, and that perfect face would pull her through --- but how long could she keep such a face sneaking drinks to fortify her for the next shot?

Monday Glamour Starter --- Gail RussellGail Russell’s fate was sealed when friends from school told a Paramount talent scout about the Hedy Lamarr of Santa Monica High, which was Gail alright, only she couldn’t act and didn’t much want to. This girl had as much business being a movie star as I would being an astronaut. The price she paid in showing up for that audition was a lifetime’s damnation, for no one got less joy out of celebrity-dom than Gail Russell. Nineteen when she walked through the gates, Gail’s looks got the pass others would have waited years to earn, but then, most of them would had have more experience, if not talent. Gail had neither. She knew it and so did Paramount, but they had departments to fix all that, and the girl was nothing if not pliable. Terrified might be a better word, for she was beset with stage fright approaching paralysis, and crying fits, then vomiting, would often as not conclude each take. She’d become a joke among producers in the know as to her limitations, but they were committed to the packaging and sale of Gail Russell, and toward that end, thrust her almost immediately into leads. Veterans such as Ginger Rogers and Ray Milland were patient with her --- perhaps they a saw a mirror of their own youthful fears in her doe-eyes, but directors like The Uninvited’s Lewis Allen were charged with getting a performance out of her, and that sometimes took hours, if not days, of blown takes and gentle guidance. Allen later said whatever useful footage they got out of Russell had to be cobbled together from brief takes and single line readings, but the camera showed mercy, and that perfect face would pull her through --- but how long could she keep such a face sneaking drinks to fortify her for the next shot?

I suspect the alcohol was there to salve a lot more than fear of a camera. Girls like Gail, that is to say fantastically beautiful girls with no confidence or protection, were fair game on Paramount preserves, as they would have been anywhere on that west coast Sodom, and I’ve no doubt she endured far worse things than the mere rigors of movie-making. If Golden Age actresses, particularly ones bereft of genuine ability or self-esteem (and that takes in a lot of them) ever told the truth about the price they really paid for stardom, we’d have a much better understanding of why so many lives ended tragically. As it is, most of them took secrets of studio abuse to (early) graves, but judging by oft-torturous paths in getting there, it must have been some really heavy baggage they were carrying. Gail reached a point where she didn’t make friends with anybody (maybe because those executives were all too anxious to make friends with her), and the work never really got any easier. She was congenial enough with Diana Lynn on Our Hearts Were Young and Gay (with her in this shot), but then Diana got her through with off-set coaching and relentless bucking-up. Gail’s temperament was well matched with Alan Ladd’s --- both crippled by insecurity, but their teamings didn’t click like Ladd’s with Lake (Veronica, that is). Fan magazine’s aptitude for invention really went into high gear with Russell --- she gave them just nothing to build from. Home life wasn’t something she’d talk about. Her parents favored a brother and made little pretense to the contrary. Playing the marquee lure off-screen was quite beyond her, since she never understood that game and couldn’t play it if she did.

John Wayne used Gail in two for Republic --- Angel and The Badman and Wake Of The Red Witch --- and gladly ponied up the loaner fee of $125,000 for her services. Of course, Paramount got the best of that deal. Some allege Russell herself was getting an appalling $125 per week. That’s probably low, but I’ll bet not by much. The one time she got credit for stirring up some dish was ironically a lot of fuss over probably nothing --- an alleged affair with her married co-star Wayne that was more likely a product of misunderstanding and a maniacally jealous wife poised to clean Wayne’s clock in a divorce court. That she did, using Gail as a battering ram, but by this time (1953), Russell’s star was in rapid descent, having been dropped by Paramount (for the drinking as much as public apathy). The work she got (practically none) plus the marriage she’d had (Guy Madison, with whom she’s beaching and nightclubbing here) were adding up to has-been status from which she’d never recover. Gail may have imagined she’d do better as an independent, but the reputation preceded her, and now without Paramount running interference, those DUI stops were landing on front pages all over town. In one particularly frightful incident, she ran her new Cadillac convertible through the front window of a coffee shop and injured the janitor on duty. It was 1957, and she was just 32. Here’s the photo taken right after it happened. Gail’s trying to find her driver’s license. Chances are she didn’t have one, as she’d racked up so many suspensions.

Nothing came harder than work for a discarded actress of a certain age in the fifties. Once they hung the dipso label on you, it became well nigh impossible. Director Joseph Losey told a sad story in which days (and nights) were spent trying to get one sustained take out of Gail. She finally confessed that anything beyond a line or two was out of the question --- unless she had a drink. Losey had been warned about that, of course, but left without a choice, he let her tank up and do the scene half-lit. This time he got what he needed (and by the way, Russell received excellent reviews for The Lawless), though she’d tearfully confess the real problem was that ongoing distaste for acting. With no other livelihood a viable option, Gail had to go on, but her road was filled with disappointment and false starts. A sanitarium layover in Seattle didn’t help --- how could she overcome the demons when there wasn’t any work? Once again, John Wayne lent a hand, casting her in a 1956 Randolph Scott western he produced, Seven Men From Now. That one didn’t get a lot of attention then, but now it’s a seminal fifties classic, and may prove to be her best remembered film. She’s good in it too, but wan, tired, and not at all what her fans expected to see after so long a wait. The final years found Russell vying for crumbs with other actresses who’d gotten the studio go-by --- a Perry Mason guest spot came down to the wire, but Martha Vickers took that dubious prize. They finally found Gail after several days quiet in her one-room apartment --- dead of a heart attack at 36. Bottles were all over the place. That was 1961, and columnists were reminded again of the sad afterlife of Paramount luminaries when Alan Ladd showed up at Gail’s funeral, drunk and muttering incoherently through the service. Maybe he was reflecting upon the fate of this sad girl, or anticipating his own, for he would die three years later under similar circumstances.

Still Stuck In The 21st CenturyJust think, if it were only sixty years ago, you could turn on your radio tonight at 8:oo and hear Edgar and Charlie on CBS. This ad's been laying around the scanner for a long time, never seeming to find a place in previous postings (even though Bergen and McCarthy have been subjects of earlier Greenbriar stories --- go HERE and HERE). Of course, there are plenty of these old radio programs available on CD --- it's amazing how many of the biggest names did guest appearances on the Bergen show. I've read that Edgar expressed himself primarily through the dummies, and that he was actually a rather aloof individual when not in character(s), sort of like Michael Redgrave in Dead Of Night, only funnier. I suppose if you spent an entire career with a dummy in your lap, you might well lose part of yourself in the process --- of course, earning a million dollars with the dummy on your lap would no doubt compensate for a lot of that.

Still Stuck In The 21st CenturyJust think, if it were only sixty years ago, you could turn on your radio tonight at 8:oo and hear Edgar and Charlie on CBS. This ad's been laying around the scanner for a long time, never seeming to find a place in previous postings (even though Bergen and McCarthy have been subjects of earlier Greenbriar stories --- go HERE and HERE). Of course, there are plenty of these old radio programs available on CD --- it's amazing how many of the biggest names did guest appearances on the Bergen show. I've read that Edgar expressed himself primarily through the dummies, and that he was actually a rather aloof individual when not in character(s), sort of like Michael Redgrave in Dead Of Night, only funnier. I suppose if you spent an entire career with a dummy in your lap, you might well lose part of yourself in the process --- of course, earning a million dollars with the dummy on your lap would no doubt compensate for a lot of that.

Beginning Of The End For John Gilbert

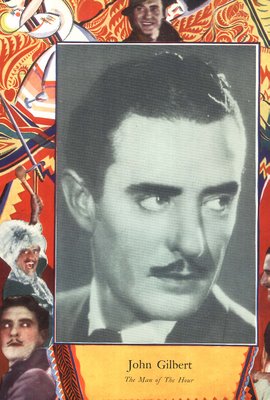

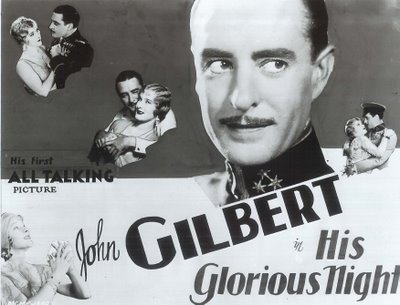

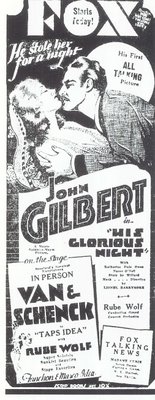

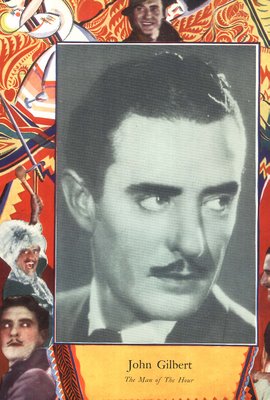

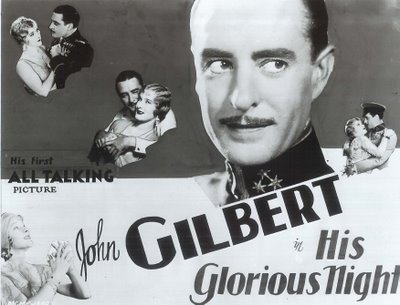

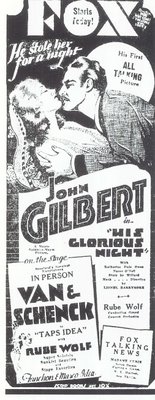

Beginning Of The End For John Gilbert I have never understood the collapse of John Gilbert’s stardom that followed the coming of sound. He’d been the screen’s "Man Of The Hour" (as witness this trade ad) and had appeared in an unbroken string of profit pictures, some of these among the biggest hits of the silent era --- The Merry Widow, The Big Parade, Flesh and The Devil. Even the least of his formula vehicles consistently went in the black --- The Show, Four Walls, Masks Of The Devil. The myth of a "white voice" was disposed of years ago, but it died hard, and carried a lot of persuasive force for many decades after Gilbert’s career had been smashed by its cruel implications. How could a man at the very summit of popularity find himself so completely discredited within less than a year, abandoned by the public, his pictures losing money one after another? It all happened between October of 1929 and the autumn of the following year, when The New York Times would refer to Gilbert’s following in the past tense. Contrary to legend, it was not an "overnight" plummet brought on by His Glorious Night. Indeed, that one was a financial success, and it wasn’t Gilbert’s talking debut in any case.

I have never understood the collapse of John Gilbert’s stardom that followed the coming of sound. He’d been the screen’s "Man Of The Hour" (as witness this trade ad) and had appeared in an unbroken string of profit pictures, some of these among the biggest hits of the silent era --- The Merry Widow, The Big Parade, Flesh and The Devil. Even the least of his formula vehicles consistently went in the black --- The Show, Four Walls, Masks Of The Devil. The myth of a "white voice" was disposed of years ago, but it died hard, and carried a lot of persuasive force for many decades after Gilbert’s career had been smashed by its cruel implications. How could a man at the very summit of popularity find himself so completely discredited within less than a year, abandoned by the public, his pictures losing money one after another? It all happened between October of 1929 and the autumn of the following year, when The New York Times would refer to Gilbert’s following in the past tense. Contrary to legend, it was not an "overnight" plummet brought on by His Glorious Night. Indeed, that one was a financial success, and it wasn’t Gilbert’s talking debut in any case.

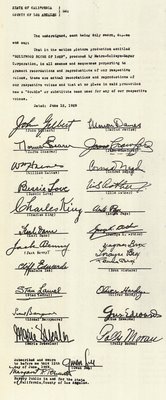

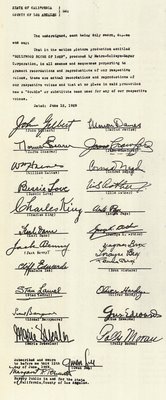

He’d started 1929 with another hit, albeit silent (featuring synchronized music and effects). That was Desert Nights, which opened in March. Gilbert’s voice had actually been heard from the screen prior to this, in a special short (Voices Across The Sea) commemorating the opening of the new Empire Theatre in London. He was shown exiting the lobby with Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, and Marion Davies, joining in their chorus of praise for the lavishly appointed showplace. This subject would have seen little play in the U.S., but it was John Gilbert’s debut in sound. Most of MGM’s other artists made talking bows in The Hollywood Revue Of 1929, which had its opening in June of that year, and ran through remaining months to enormous crowds ($1.1 million profit). Concern over voice authenticity resulted in an affidavit (shown here) in which all the stars "certify" they’ve not been doubled for purposes of recording. Gilbert and Norma Shearer contributed a rendition of the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, first played straight, then spoofed up with twenties slanguage. Two-color technicolor augmented what surely was considered the highlight of this show and the stars even let their hair down for a comic exchange with director Lionel Barrymore. Gilbert plays the Shakespeare in earnest fashion, acquits himself well during the lampoon portion, then relaxes and appears to ad-lib in his concluding exchange with Shearer and Barrymore. This could not have been considered anything but an auspicious talking showcase for the actor, and audiences responded accordingly. No published review I’ve seen had anything other than praise for Gilbert in The Hollywood Revue Of 1929.

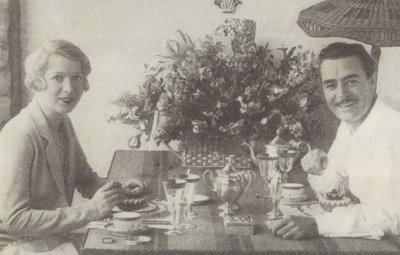

Was Louis Mayer out to get him? There was another of those real-life Hollywood dramas in which Gilbert was supposed to have punched the studio executive's face when Mayer made an indelicate remark about Greta Garbo, long recognized as The Great Love of Gilbert’s Life (here during a brief shack-up period they’d recently enjoyed). Greta had allegedly stood up Jack at the altar that very day, and tempers were running high, so much so that a bloodied Mayer swore he’d finish John Gilbert if it’s the last thing I do (or words to that effect). Later research suggests that Garbo was at work that day and never intended to marry Jack or anyone else. I suspect this is one of those stories too good to debunk, and since it had its origins with long-retired silent star eyewitnesses (Eleanor Boardman chief among them), how can anyone say with certainty that it didn’t happen? There was hostility toward Gilbert within Mayer’s camp, but this was owing to the fact that Loew’s head Nicholas Schenck had quietly pledged Gilbert to a renewal of his contract at fantastically generous terms (and without consulting Mayer) in December of 1928. This New York office chicanery tended to undermine the authority of the studio bosses where talent was concerned, but what could they do? --- Loew’s owned MGM, and Schenck required neither their permission nor approval. This was probably where John Gilbert really lost his moorings, and one couldn’t help but smell a rat by the time His Glorious Night showed up in October 1929.

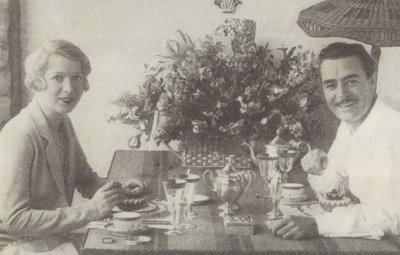

The biggest stink bomb chucked in Gilbert’s direction came from Variety. None of the other reviews approached this one for sheer vitriol. I’m convinced it was a ringer, planted there to start him down the skids. A few more talker productions like this and John Gilbert will be able to change places with Harry Langdon. His prowess at love-making, which has held the stenos breathless, takes on a comedy aspect in "His Glorious Night" that gets the gum chewers tittering at first and then laughing outright at the very false ring of the couple of dozen "I love you" phrases designed to climax, ante and post, the thrill in the Gilbert lines. Variety’s snide review went way beyond other critical reactions to the film. Both Mr.Gilbert and Catherine Dale Owen contribute competent performances, said The New York Times, and exhibitor reaction, which could be tactless and brutal in the best of times, reserved their brickbats for the film itself and specifically Metro’s sound recording, while others praised His Glorious Night and limited complaints to what they considered unreasonable rental terms ($85.00 in one situation). John Gilbert returned from his European honeymoon with Broadway actress Ina Claire just after the picture opened (here they are at afternoon tea), and according to a later interview, found Metro publicists waiting at the dock in gleeful anticipation, scathing reviews clutched in their hands. Maybe Gilbert’s memory was colored by the truly awful developments he’d witness over coming months, because at this point, the only scathing notice was Variety's --- The love lines, about pulsating blood, hearts, and dandelions, read far better than they sound from under the dainty Gilbertian mustache --- another vicious quote from that very suspect review. General press coverage would eventually follow suit --- bad Gilbert pictures wouldn’t help. Redemption was actually shot before His Glorious Night, but adjudged so lousy as to be shelved for nearly a year. 1930 would see the release of that and creeping doubt as to John Gilbert’s boxoffice future. Mind you, Redemption was the first of his MGM output to lose money (His Glorious Night had returned $202,000 in profits). The power of suggestion (but whose?) had finally extended to The New York Times by September of that year --- John Gilbert, who was once the great lover of the silent screen, cannot be said to have maintained his lofty position since dialogue was coupled with films. He has only appeared in two films, which have not increased his popularity. He has recently finished work in another audible film called "Way For A Sailor", which so far has not been presented, and on which his future screen success depends largely. Well, in such circumstance as this, how could Way For A Sailor be anything other than a failure? Indeed, it would tank ($606,000 lost) as would every single Gilbert vehicle to come (excepting Queen Christina, but that was Garbo’s show, and Gilbert’s was charity casting). Chaplin tried to throw him a lifeline by announcing a forthcoming slate of silent dramas to star Gilbert --- in March 1930 --- but this was likely more of CC’s posturing against the encroachment of sound and not to be taken seriously.

I finally realized a near-lifelong dream of seeing His Glorious Night at the 1997 Cinecon. It was a movie I’d read about since Arthur Mayer and Richard Griffith’s The Movies book back in sixth grade, and Gilbert’s voice, though nowise approaching a Ronald Colman or William Powell, was still more than adequate, even if it’s not what we’d expect of the silent Gilbert. It seems to me the man was wiped out less by the failure of his performance and popularity than by the perception of failure, fed by a press and public easily influenced by rumor and suggestion. It happened to Burt Reynolds in the eighties, and we still see parallels today. The recent course of Tom Cruise’s career comes to mind, and there are others. Stardom was seldom so fleeting a thing as John Gilbert experienced it, but no actor, today or the day after tomorrow, should ever imagine that this couldn’t happen to him.

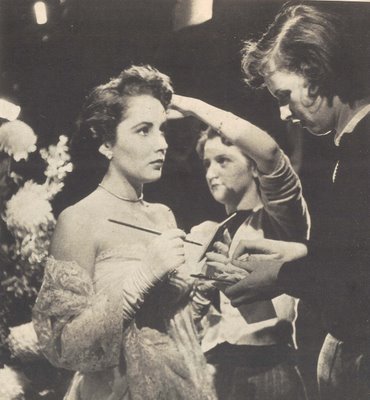

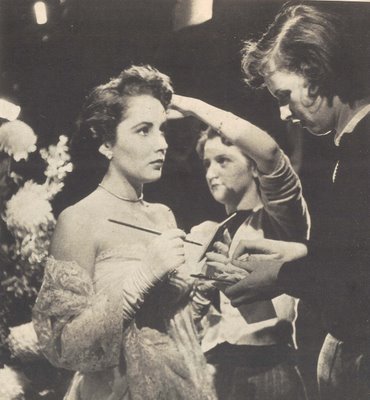

Liz Loose In LondonNobody talks about Conspirator anymore, but they sure did when it was new in 1950. Actually, it wasn’t new then, filming having started back in November 1948 and then withheld from release for over a year. Perhaps they wanted to spare audiences the shock of seeing a just-turned seventeen Elizabeth Taylor in the arms of thirty-seven year old Robert Taylor. Delaying the open may also have been recognition of the fact they had a weak picture that needed to play off quietly before the real grown-up showcase for Liz, Father Of The Bride, bowed in June of ’50. Whatever the reason, Conspirator was still big news for Taylor's fan base, whose excitement over the teenage star could only be quenched by reams of location and behind-the-scenes profiles celebrating her trip to England and first-time adult role opposite veteran Bob. The intensive marketing of average (or below that) pictures was certainly nothing new in 1950 --- goodness knows we have more of it today than ever --- but fan magazine coverage from that era reveals a lot about how the product was sold and who they were targeting. With Conspirator, it was teenage girls in the crosshairs of those monthlies; invited to share in the fantasy romance of an actress still in school whisked overseas to play at being a woman married to Robert Taylor. The British shoot was necessitated by that country’s freezing of Metro exhibition receipts collected in U.K. theatres --- such money could not be brought home --- it had to be reinvested in production over there, thus providing employment for native cast and crew. Conspirator had a British director (Victor Saville) and co-stars --- note the group taking tea here during a break in filming --- that girl on the right is a young Honor Blackman, her Pussy Galore still fifteen years in the future when she made this.

Liz Loose In LondonNobody talks about Conspirator anymore, but they sure did when it was new in 1950. Actually, it wasn’t new then, filming having started back in November 1948 and then withheld from release for over a year. Perhaps they wanted to spare audiences the shock of seeing a just-turned seventeen Elizabeth Taylor in the arms of thirty-seven year old Robert Taylor. Delaying the open may also have been recognition of the fact they had a weak picture that needed to play off quietly before the real grown-up showcase for Liz, Father Of The Bride, bowed in June of ’50. Whatever the reason, Conspirator was still big news for Taylor's fan base, whose excitement over the teenage star could only be quenched by reams of location and behind-the-scenes profiles celebrating her trip to England and first-time adult role opposite veteran Bob. The intensive marketing of average (or below that) pictures was certainly nothing new in 1950 --- goodness knows we have more of it today than ever --- but fan magazine coverage from that era reveals a lot about how the product was sold and who they were targeting. With Conspirator, it was teenage girls in the crosshairs of those monthlies; invited to share in the fantasy romance of an actress still in school whisked overseas to play at being a woman married to Robert Taylor. The British shoot was necessitated by that country’s freezing of Metro exhibition receipts collected in U.K. theatres --- such money could not be brought home --- it had to be reinvested in production over there, thus providing employment for native cast and crew. Conspirator had a British director (Victor Saville) and co-stars --- note the group taking tea here during a break in filming --- that girl on the right is a young Honor Blackman, her Pussy Galore still fifteen years in the future when she made this.

Metro had to fend off a militant Los Angeles Board Of Education when time came to book Elizabeth Taylor’s passage to England. As she was still a minor, there had to be provisions made for her schooling, and that’s where the schoolmarm shown here with Liz comes in. Her name was Miss Bertina Anderson, and columnists of the day assured us that she was accredited and experienced (small comfort there --- as most of my teachers were as well, but that didn’t modify foul dispositions or sadistic inclinations displayed by a number of them!). Miss Anderson is pointing out their destination here on the map. Yes, it looks like England, all right. I’m not so sure how Bertina’s lessons took with Liz, having been reminded of an interview I once read where Shelly Winters said the only things she ever observed Taylor reading were gossip columns and the trades. However futile her instruction may have been (even with Bob Taylor’s help, as shown here), the venerable educator is said to have strictly maintained the three-hour a day schooling that was observed in bite-sized increments between takes. As you’ll note from these stills, Liz made quite a splash around London-town, whether standing in queue for ration tickets (no way they’d let her starve in any event) or posing with guards at Buckingham Palace.

Liz may have looked the part of a grown woman, but didn’t quite have the voice to pull it off. She made Margaret O’Brien sound like Mercedes McCambridge by comparison. Liz was seventeen playing eighteen and acting like twelve. It’s difficult to fathom Robert Taylor’s interest in her --- wait a minute, what am I saying? After all, Bob did request of the cameraman that he shoot only from the waist up (Bob was 37 playing 31 and acting 17). Liz later said their love scenes were somewhat enlivened by her leading man’s tongue having wandered very near her tonsils. Further on-set complications included a Bob/Liz tangle wherein our girl’s bathrobe opened wide to reveal a breathtaking physical landscape surely the equal of any natural wonders to be found amongst the British Isles. The footage was carefully inspected back in Culver City… very carefully inspected. After twelve or so months of detailed consideration and repeated viewing, executives decided that the offending moment would, indeed, have to be discarded (never mind London After Midnight and The Rogue Song --- let’s find this!).

Well, I’ve ignored Conspirator itself so far, but you shouldn’t, as it’s one peach of a cold war Gaslight retread that pits child bride Liz against Communist traitor husband Bob, with England’s very future at stake! He’s a dashing British army officer, but that’s just on the surface. At night, he sneaks off to confer with spies in a Hammer-friendly back street London where I kept expecting Michael Ripper to turn up as a chimney sweep or barman. Here’s the question that nags --- why would a cool cat like Bob, decked out in tailored uniforms and practically tripping over medals and promotions (not to mention Liz awaiting him in their marital bed) want to tie himself up with a lot of cheerless Russkies? These guys always come off with the same lines --- One never questions the party … It is not permissible for you to fail again. Do Commie operatives act this way in real life, and if so, how do they ever get recruits? Rest assured your local Rotarians or Kiwanians would fast lose their membership if leaders acted so high-handed as this! So what’s in it for Bob, I kept asking myself, finally accepting the fact I’d never make a good Party man. Mind you, never once did those Reds thank Bob for all his treason on their behalf in Conspirator. What that crowd needed was charismatic, outwardly gracious, silken-voiced representatives along the lines of Sydney Greenstreet, Otto Kruger, or Claude Rains, instead of these weasely, dogmatic functionaries (Hitchcock got it right when he used James Mason in North By Northwest). Ever notice how Reds are always trafficking in microfilm or really tiny pieces of paper inserted within seemingly tinier pieces of paper. Like Grant Williams, their communiqués seem to shrink into a kind of infinity, and you’d think it would take a field trip to Mount Palomar to decode some of these messages. Of course, Liz stumbles across one of them in Conspirator, and showing quite remarkable perception for such an otherwise clueless character, promptly unmasks and reveals Bob’s perfidy (while they’re alone, of course, thus putting her life in immediate jeopardy). It’s all done in that over-the-top, higher octave woman’s gothic style of the Dragonwyck school, but this time with spies and espionage providing the Deus ex Machina. Conspirator is an obscure, but delightful, Metro star vehicle with a lot more to offer than its modest reputation would suggest, and it comes on TCM quite a lot. Well worth catching the next time if you’ve not seen it …

Two Endings For Bullets Or BallotsJust watched Warner’s excellent new DVD of Bullets Or Ballots and hope I won’t spoil the party for too many readers when I reveal that Eddie Robinson dies at the end. Well, he does in the ending they released, though it seems an alternate final scene was filmed (with Joan Blondell), and as shown here, he survives the final staircase showdown with Humphrey Bogart to be reunited with Blondell in a hospital room. Warners may have tested both with preview audiences, and they opted for the downer. Audio commentator Dana Polan mentions the possibility of the two endings, having seen mention of them in Warner’s original production file. I don’t think Production Code influence entered into it, however. "Pretend" gangsters going undercover didn’t have to die. Look at all the variations on this story that WB later did --- Across The Pacific, Springfield Rifle, Northern Pursuit. None of those guys perished at the end. I think what finishes Eddie here is the fact that he violates his own code of the streets by not "playing square" with mobster Barton MacLane, and all the signals are up when MacLane makes a point of crediting Eddie with having done so in the past. In fact, there are several scenes where the gangsters pay tribute to Robinson’s being a straight shooter among lawmen, never taking unfair advantage or double-crossing them. When he goes undercover with MacLane’s mob, he does precisely that, and for such a breach, he must die. This was less a matter of observing a morality code than a writer’s code. Being on the "right" side of the law doesn’t entitle you to bring down your opponent in such underhanded fashion, even if he’s otherwise got it coming. To let Robinson live at the finish would have left a slightly bitter taste in the viewer’s mouth, and that’s why I think the ending we got was the appropriate one.

Two Endings For Bullets Or BallotsJust watched Warner’s excellent new DVD of Bullets Or Ballots and hope I won’t spoil the party for too many readers when I reveal that Eddie Robinson dies at the end. Well, he does in the ending they released, though it seems an alternate final scene was filmed (with Joan Blondell), and as shown here, he survives the final staircase showdown with Humphrey Bogart to be reunited with Blondell in a hospital room. Warners may have tested both with preview audiences, and they opted for the downer. Audio commentator Dana Polan mentions the possibility of the two endings, having seen mention of them in Warner’s original production file. I don’t think Production Code influence entered into it, however. "Pretend" gangsters going undercover didn’t have to die. Look at all the variations on this story that WB later did --- Across The Pacific, Springfield Rifle, Northern Pursuit. None of those guys perished at the end. I think what finishes Eddie here is the fact that he violates his own code of the streets by not "playing square" with mobster Barton MacLane, and all the signals are up when MacLane makes a point of crediting Eddie with having done so in the past. In fact, there are several scenes where the gangsters pay tribute to Robinson’s being a straight shooter among lawmen, never taking unfair advantage or double-crossing them. When he goes undercover with MacLane’s mob, he does precisely that, and for such a breach, he must die. This was less a matter of observing a morality code than a writer’s code. Being on the "right" side of the law doesn’t entitle you to bring down your opponent in such underhanded fashion, even if he’s otherwise got it coming. To let Robinson live at the finish would have left a slightly bitter taste in the viewer’s mouth, and that’s why I think the ending we got was the appropriate one.

I'd Walk A Mile For A Black CamelWatching a bootleg DVD takes me back to the sixties when I used to struggle to bring in stations we really couldn’t get in order to see movies I really wanted to see. Parents or siblings would pass through, glance at the set, and shake their heads --- Can you even see that? --- Doesn’t that hurt your eyes? Well, what else could you do in those days? An opportunity to see Doctor Cyclops may never come again --- and besides, they were my eyes, after all, and if I was willing to forfeit them for the sake of watching The Coconuts from a distant Tennessee channel, shouldn’t I be left alone to do just that? Sometimes I wonder if the reading glasses I’m wearing now might be a consequence of some long-ago viewing of The Giant Gila Monster on High Point’s elusive Channel 8. No doubt that lesson’s still unlearned, for here I am struggling to get through a "grey market" DVD of The Black Camel, home video’s assurance of premature blindness for those fool enough to subject themselves to its 71 minutes of fleeting image and bleating sound. Actually, we never made it to the end, my struggling player and I. Just as Dwight Frye pulled an automatic and tried to back his way out of the denouement, there was a frightful lock-up and a noise from the rear speakers that sounded like The Giant Behemoth. There’s a sort of fear that grips you during moments like this. Dwight’s face is frozen upon the screen, quivering slightly, as if poised to explode and engulf the room in flames --- perhaps my Panasonic player is nearing meltdown, and that violent conflagration will send shards of razor pointed metal in my direction. Cowardice thus forced me to turn it off, so I’ll manage this post as best I can without benefit of having seen the fadeout.

I'd Walk A Mile For A Black CamelWatching a bootleg DVD takes me back to the sixties when I used to struggle to bring in stations we really couldn’t get in order to see movies I really wanted to see. Parents or siblings would pass through, glance at the set, and shake their heads --- Can you even see that? --- Doesn’t that hurt your eyes? Well, what else could you do in those days? An opportunity to see Doctor Cyclops may never come again --- and besides, they were my eyes, after all, and if I was willing to forfeit them for the sake of watching The Coconuts from a distant Tennessee channel, shouldn’t I be left alone to do just that? Sometimes I wonder if the reading glasses I’m wearing now might be a consequence of some long-ago viewing of The Giant Gila Monster on High Point’s elusive Channel 8. No doubt that lesson’s still unlearned, for here I am struggling to get through a "grey market" DVD of The Black Camel, home video’s assurance of premature blindness for those fool enough to subject themselves to its 71 minutes of fleeting image and bleating sound. Actually, we never made it to the end, my struggling player and I. Just as Dwight Frye pulled an automatic and tried to back his way out of the denouement, there was a frightful lock-up and a noise from the rear speakers that sounded like The Giant Behemoth. There’s a sort of fear that grips you during moments like this. Dwight’s face is frozen upon the screen, quivering slightly, as if poised to explode and engulf the room in flames --- perhaps my Panasonic player is nearing meltdown, and that violent conflagration will send shards of razor pointed metal in my direction. Cowardice thus forced me to turn it off, so I’ll manage this post as best I can without benefit of having seen the fadeout.

You know you’re hard-core when the authentic Hawaiian location footage makes an impression even on a disc so degraded as this. I just sat back and imagined myself at the Roxy back in the summer of 1931, watching The Black Camel first-run and marveling that Fox actually sent its cast and crew all the way to those islands for much of the principal photography --- and this was a Charlie Chan picture! Never again would that series enjoy such location splendor. There’s even the brisk sound of an ocean breeze to interfere occasionally with dialogue recording. Had this been something other than a seventeenth generation pirated DVD, I would have almost felt as if I were there! Much of The Black Camel was shot about the lobby and grounds of the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, which they say is unchanged to this day. Quite a contrast to three-wall cardboard sets that confined Roland Winters in all those miserly Monogram Chans from the forties. The Black Camel is nothing if not spacious. Warner Oland hits the beach in search of murderer --- I thought he might even get around to surfing at one point. There’s more Hawaii in 71 minutes here than Warners would give us in four seasons of Hawaiian Eye. The mystery itself had me stumped. I guessed wrong about the killer, though I missed some clues when my DVD lurched forward a few times, no doubt exercising its own prerogative with regards to speeding up the pace. I’ll also confess to having dozed off a time or two, a gentle slumber borne upon the lilting strains of Warner Oland’s singular voice. His scenes with Bela Lugosi are a highlight, by the way. Masters at work, both looking dapper and fit amidst the Royal Hawaiian’s luxury. I understand Bela picked up a grand a week for doing The Black Camel, plus he got the red carpet works living right there where they filmed it. Nice to see Lugosi enjoying life (as here in the hotel’s dining room --- bon appetit, Bela!). I’ll bet he looked back on this happy sojourn years later with wistful fondness, maybe during breaks on Bride Of The Monster (though I’m sure he didn’t get many breaks on that one).

These arresting ads were specially designed for the Fox Theatres chain in 1931. Managers were carefully instructed as to the most effective techniques for selling The Black Camel. This picture is a much better story of Earl Derr Biggers’ Chinese detective, Charlie Chan, than was Charlie Chan Carries On, they said, and we’ll have to take their word, I suppose, because Carries On is lost and has been since a disastrous warehouse fire in 1937 that took out much of the Fox library, including four of the Chans. Regarding Lugosi’s character, the home office pointed out that because of the prevalent disregard of mysticism, we have played him down. Now what do you suppose mystics had done back in 1931 to get people in such a lather? Anyway, The Black Camel would be sold as a straight mystery story, leaving out all direct references to sinister forces and murder and weirdness. That’s rather like squeezing all the juice out of the orange before serving, but management felt pretty safe in predicting a satisfactory boxoffice total within these guidelines. Earl Derr Biggers came through with a ringing endorsement --- The Fox picture made from my novel, The Black Camel, delighted me in every way, and I feel sure all Charlie Chan’s admirers who see it will share my pleasure. Rarely, to my way of thinking, has the plot of a book been transferred to the screen so neatly and so successfully. Cast and direction are excellent, and the result is the sort of picture an author dreams about, but doesn’t always get. As for Warner Oland’s interpretation of Charlie Chan, in this second picture of the series, he settles the matter for all time. He IS Charlie Chan. Like all the Fox Chan mysteries, The Black Camel made money. With a negative cost of $223,000, the picture took domestic rentals of $357,000, with foreign adding another $114,000. Final worldwide total was $471,000 for a profit of $60,000.

These arresting ads were specially designed for the Fox Theatres chain in 1931. Managers were carefully instructed as to the most effective techniques for selling The Black Camel. This picture is a much better story of Earl Derr Biggers’ Chinese detective, Charlie Chan, than was Charlie Chan Carries On, they said, and we’ll have to take their word, I suppose, because Carries On is lost and has been since a disastrous warehouse fire in 1937 that took out much of the Fox library, including four of the Chans. Regarding Lugosi’s character, the home office pointed out that because of the prevalent disregard of mysticism, we have played him down. Now what do you suppose mystics had done back in 1931 to get people in such a lather? Anyway, The Black Camel would be sold as a straight mystery story, leaving out all direct references to sinister forces and murder and weirdness. That’s rather like squeezing all the juice out of the orange before serving, but management felt pretty safe in predicting a satisfactory boxoffice total within these guidelines. Earl Derr Biggers came through with a ringing endorsement --- The Fox picture made from my novel, The Black Camel, delighted me in every way, and I feel sure all Charlie Chan’s admirers who see it will share my pleasure. Rarely, to my way of thinking, has the plot of a book been transferred to the screen so neatly and so successfully. Cast and direction are excellent, and the result is the sort of picture an author dreams about, but doesn’t always get. As for Warner Oland’s interpretation of Charlie Chan, in this second picture of the series, he settles the matter for all time. He IS Charlie Chan. Like all the Fox Chan mysteries, The Black Camel made money. With a negative cost of $223,000, the picture took domestic rentals of $357,000, with foreign adding another $114,000. Final worldwide total was $471,000 for a profit of $60,000.

Thank You, Fox, For Mr. Moto

Thank You, Fox, For Mr. Moto